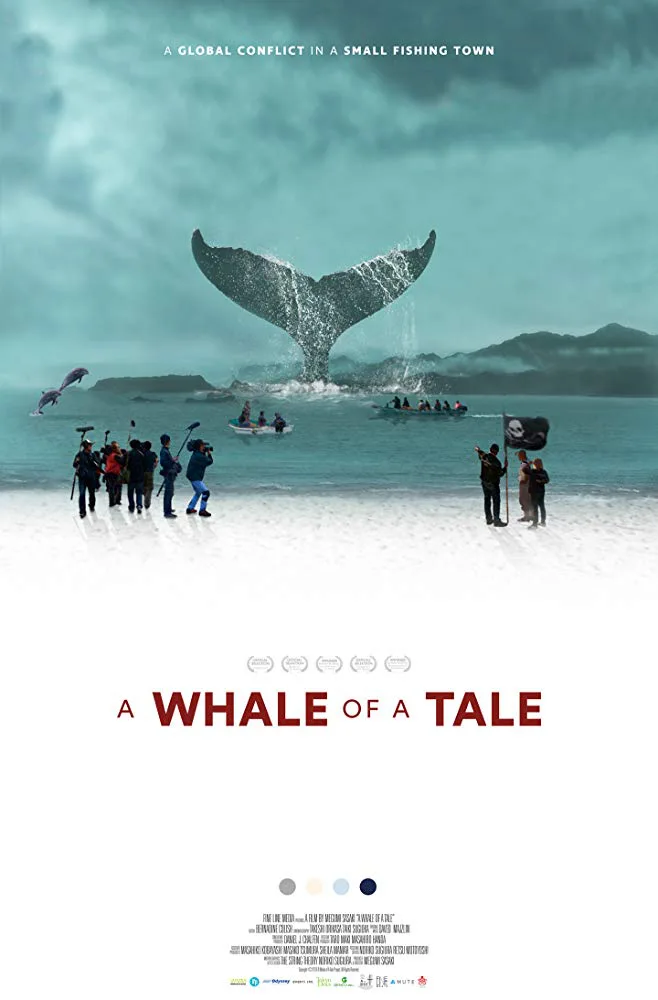

Louis Psihoyos’ 2009 anti-whale hunting film “The Cove” was one of the most successful activist documentaries of all time, if you count getting the world’s attention as one of its main goals. Not only did it win the Oscar for Best Documentary, but one of the protestors in the film about stopping whaling in Japan, Ric O’Barry, was able to brandish the film’s text message activism one time and to hundreds of millions of TV viewers.

Needless to say this all brought a lot more attention to the small town of Taiji, where dolphins and whales are hunted to be eaten, the best ones sent to aquariums around the world. If you ask a Westerner, it’s a gruesome horror show that must be stopped immediately. But the Japanese men who have been doing this for generations, they’ll tell you it’s just business, it’s their culture, these are just fish. But when it comes to the activists who have showing up in Taiji since the movie, one resident states with trepidation, “There’s nothing worse than a scene in an Academy Award-winning film.”

With access to the small town of Taiji and its inhabitants that the extremely outsider-made “The Cove” did not have, director Megumi Sasaki listens to their side of the debate. The men speak matter-of-factly, without the air of trying to create good PR, about something they have been doing for generations to support the people of their community.

Sasaki also documents the very intense disconnect between whalers and protesters, and it makes for a handful of gripping moments of clashing passions. One of the best involves Steve, a White teacher who now lives in Japan, swimming out to where the dolphins have been cordoned, just to toss them a ball to play with before they die. The scene ends with two sides, a Japanese police officer and Steve, agreeing that while Steve did not break the law, he did not use manners, which is against the Japanese way. The two men then bow to each other. It’s one of many morally complicated scenes captured in this story, but to a point: the tragedy of this disagreement doesn’t inspire heavy emotion from this telling, so much as frustration.

Sasaki does try to have a personal angle with Jay Alabaster, an Associated Press reporter who has lived in Japan for over a decade. He later moves to Taiji to become a true resident to the problem, but even then he only observes with hopes of turning it into a book. Jay becomes a quaint mascot for the movie, showing what can be achieved by recognizing the other side. But for the intent that comes with his passages (which are sometimes overlong within some rough-around-the-edges filmmaking), even his passion is distilled with a cold documentary touch.

It becomes clear throughout the doc that neither side of this debate is going to budge. As a filmmaker’s act to show both sides of one argument, “A Whale of a Tale” is initially highly intriguing, but becomes exhausting narratively as we slam from one immovable wall to the other and back again. Though it reports on this issue over the span of five years, there doesn’t seem to be all that much commentary aside from “it’s more complicated than you think.” The end to the movie is surprising, if only because money starts to speak in a way one wouldn’t initially expect.

The biggest success for “A Whale of a Tale” is in how it corrects the biggest flaw of “The Cove,” which came from an inclination we all have: to cast real-life people as one-dimensional heroes and villains, good and evil. In Sasaki’s unofficial but necessary sequel to “The Cove,” she aptly considers how both sides of a conflict believe they are doing the right thing.