Be careful what you ask for. You might get it.

– Old saying In an early scene of “A New Life,” a wife presents the case against her husband: “You leave home at 7 o’clock in the morning and you get back home in time for the 11 o’clock news, which you watch.” Their marriage has been over, she says, ever since their daughter left for college. Now she wants out. Her husband protests that he loves her, to no avail. She wants a divorce so bad she even lets him have the Knicks tickets.

Time passes. Wounds heal. She enrolls in school. He makes money in the stock market. Neither one of them finds anybody new. One day, she suggests that they bring each other to a singles’ party. He agrees.

What the hell. At the party, he gets into a fight and leaves early. She meets a handsome younger sculptor (John Shea) who seems recycled right out of the Alan Bates role in “An Unmarried Woman.” A little later, the husband has an anxiety attack that feels like a heart attack, and when he goes to the emergency room and feels the hands of the woman doctor on his body, his heart goes hippity-hop.

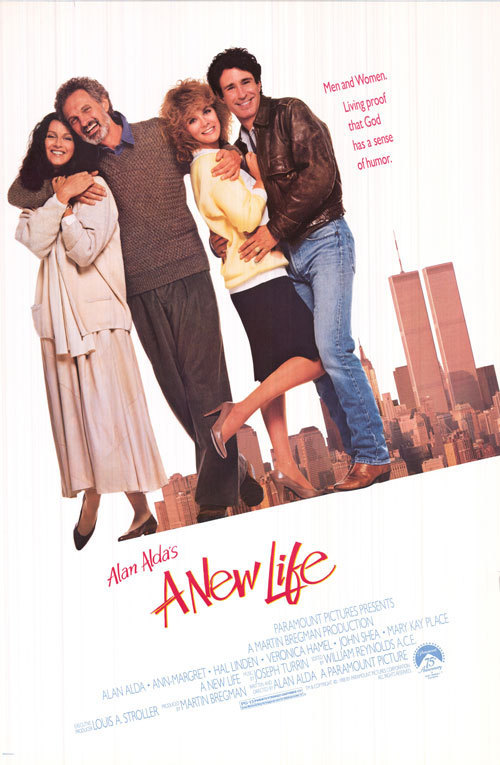

And that is the setup for “A New Life,” Alan Alda’s slice of life comedy about divorce and relationships. The ironies are easy to spot.

Alda’s ex-wife (played by Ann-Margret with luxurious sensuality) wants a man who will pay attention to her, and she gets more than she bargained for – an obsessive, compulsive control freak. The Alda character just wants to find another woman he can love, but he gets more than he bargained for, too. The doctor he eventually marries (Veronica Hamel) doesn’t want to simply love and be loved, she wants a baby, and her biological clock is ticking. And so Alda, to his intense confusion, finds himself a father again, in his 50s.

“A New Life” shows us two new lives, or even four, depending on how you count, and that’s a refreshing change. This genre of movie usually follows only one of the partners after the split-up. In its willingness to give equal billing to the Alda and Ann-Margaret characters, however, it rushes ahead into their adventures as newly single people, and that creates a question that overshadows the whole movie: Why did they split up in the first place? We believe her when she says her workaholic husband spent all of his time on Wall Street. But we can see throughout the movie that this man and this woman are better suited to each other than to the new partners they so hopefully embrace. What’s the problem? Why is Alda incapable of altering his lifestyle for his wife of 25 years, only to change everything – even becoming a new parent – for his second wife? The movie doesn’t avoid this question, it just never answers it.

The real answer may be that there is no story if the couple stays together. All happy families are alike, but only an unhappy family is interesting at the box office. What we get, then, is a series of interesting scenes, well-acted, sometimes funny, sometimes exciting and sometimes very moving – but all of them unnecessary. Take, for example, the movie’s emotional high point, when Alda is at last able to overcome his squeamishness to be with his second wife when she delivers their baby. This is a powerful scene, but it still leaves one question unanswered: Why are they married to one another? What’s best about the movie are its many moments of close observation, which are easy to identify with. After Alda develops a crush on Hamel, for example, she plays slightly hard to get, and when she finally agrees to go to a Knicks game, he lets out a whoop of glee.

(Is part of his joy inspired by the knowledge that he will not have to miss the game for the date?) The breakup of the relationship between Ann-Margret and the possessive sculptor is dramatized in a scene where she boards a plane for a conference in Washington, only to find him in the next seat. “I thought I’d come along,” he says. “Isn’t this a great surprise?” The look on her face is indescribable.

Other good moments are provided by the relationship between Alda and Hal Linden, as his business partner and best friend. Linden is an unreconstructed male chauvinist bachelor, still chasing skirts at 50, utterly convinced that marriage is a jail and men are the prisoners. He has lines so cheerfully sexist that they peal with the ring of truth. A parallel relationship between Ann-Margret and her best friend (Mary Kay Place) is not quite so entertaining; their conversations run more toward sincerity than cynicism.

Like “Four Seasons,” his debut as a writer-director, “A New Life” is Alda’s version of various rites of passage. His ambition is not to bring anything new or revealing to his subject matter, but to see it as it is. If you told him you recognized all of the characters, that would be a compliment. The result is a little hard to evaluate. Alda’s purpose is to show us fairly typical people going through fairly typical things. They live, we watch. On that voyeuristic level, the movie works.