“When I look at you, I don’t know what I’m seeing. A chimera, that’s what I’m seeing.” In Sebastián Lelio’s new film “A Fantastic Woman,” these breathtakingly cruel words are said to Marina (Daniela Vega), a trans woman in mourning for her dead lover Orlando (Francisco Reyes), by Orlando’s ex-wife Sonia (Aline Kuppenheim). Sonia speaks with such calm confidence, such chilling certainty, it pulls the entire film—and the problem it portrays—into sharp focus. Similar to his 2013 film “Gloria,” where a 58-year-old woman struggled to assert her identity—sexual and otherwise—in a world where aging people are supposed to be invisible, in “A Fantastic Woman,” a trans woman fights for simple human respect in a world intractable with hatred. Suffused with fantastical elements, dreamlike sequences and hallucinatory images, “A Fantastic Woman” stars Daniela Vega, a trans actress, and her performance roots the film in a kind of intimate verisimilitude.

Marina is first seen on a romantic dinner date with Orlando. They drink and eat, dance, stumble home together, make love. Orlando is much older than Marina, and clearly wealthy (he owns a textile mill), whereas Marina waits tables and pursues a singing career. But then Orlando suffers an aneurysm and dies on the operating table after a panicked Marina drives him to the emergency room. It is there her trouble begins. She is treated with suspicion by hospital staff. She is referred to as “he” because her license hasn’t been changed to reflect her gender identity. The cops arrive to question her. Orlando had bruises on his body after falling down the stairs during the aneurysm, and there is suspicion of foul play. Marina is asked if Orlando was paying her for sex. She is not granted the respect a grieving wife or girlfriend would receive. She is instantly thrust out of the warm circle of belonging which Orlando represented for her.

Orlando’s ex-wife and son (Nicolás Saavedra) want Marina out of Orlando’s apartment. She is forbidden to come to the wake or funeral. She is not allowed to keep Orlando’s dog. Meanwhile, a detective from the Sexual Offenses Unit (Amparo Noguera) visits Marina at work to ask more questions. She forces Marina to come to the station and submit to a humiliating physical examination. All Marina wants to do is be allowed to say goodbye to Orlando, to grieve publicly. She’s not just treated as a second-class citizen. She’s treated as a non-Person.

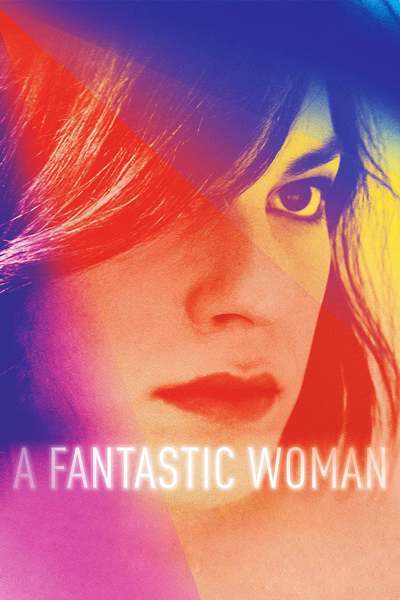

Lelio approaches this material with sensitivity and empathy. There’s restraint in his style, eloquent as it is. He weaves in elements from melodrama, from noir. Marina discovers a mysterious key in Orlando’s possessions, and her quest to discover what the key might unlock, makes up a large sequence of the film. “A Fantastic Woman” is filled with color, lights shifting from red to green to blue to yellow, bodies bathing in light, drowning in shadows. It’s an amorphous world, the borderline between night and day, consciousness and unconsciousness, is blurred. Cinematographer Benjamín Echazarreta has placed Vega at the center of every frame, her face, the back of her neck, her full body. She walks the streets of Santiago. Sometimes she is viewed from behind, sometimes she is viewed from across the street, the camera moving with her as she walks past a construction site, or along a block of storefronts. She is usually alone in the frame. Santiago often appears emptied-out of people in “A Fantastic Woman.” These choices suggest Marina’s isolation, as well as her vulnerable visibility. It’s like she’s a walking target.

Marina sees Orlando everywhere, coming back to haunt her. A chaotic dance floor coalesces into a choreographed stage show led by Marina, in a dazzling silver and gold costume, an exaggerated version of womanhood. In one scene, she trudges down a street into a wind so strong her body is almost parallel to the ground, fighting against it. There are times when she stares directly at the camera with a level gaze. These surreal and wordless sequences launch us into Marina’s experience. (In a daringly obvious choice, Aretha Franklin’s “You Make Me Feel Like a Natural Woman” plays on Marina’s car radio as she goes to meet Sonia. “A Fantastic Woman” does not pull its punches.)

None of this would be possible without Vega’s performance. She’s the one who really allows us into the experience of the film, and of the character. There are moments when a horrible grief rises up in her eyes at the loss of Orlando, and yet she has to stuff it down in order to deal with whatever is going on in the present moment. The way she walks is brisk and efficient, but with tension vibrating around her, her shoulders tense and squared-off. A small punching bag hangs by the door of her apartment, and she throttles it before she leaves every morning. Marina bottles up a lot of stuff just to get through the day. Vega shows us why. It may be satisfying to see Marina make a triumphant eulogy speech and win over Orlando’s family, but “A Fantastic Woman” is not interested in anything that simplistic. What does it even mean to be “a fantastic woman”? What does that look like? Does Marina know? She knew who she was with Orlando. Now that he is gone, she questions everything.

“A Fantastic Woman” is not just about a person asserting her right to be treated like a person. It’s also about Marina’s conflicting views of womanhood, and how she might (or might not) fit into it. She lies naked in bed, knees bent, with a round mirror placed over her genital area. She stares down at the mirror, her reflected face looking back up at her from between her legs. It’s a stunning shot, filled with poetic and metaphoric resonance.

Who cares what’s between her legs? Why does it matter so much? Why does it matter at all?