When communism comes to the republic of Georgia, one of its great chefs is philosophical: Marxism will pass away, he observes, but great cuisine will live forever. It is perhaps relevant that the chef making this remark is a Frenchman, who has moved to the Georgian capital of Tbilisi out of love for a woman.

Nana Dzhordzhadze’s “A Chef in Love,” which was filmed in Paris and the former Soviet Georgia, paints the chef, named Pascal Ichac, as a great eccentric bon vivant: a man capable of identifying any vintage by its bouquet, of finding a bomb at the opera by his nose alone, of criticizing another chef’s recipes by the aromas that float in through an attic window. In the past he has also been something of an opera singer and, it is rumored, a gigolo on a cruise ship on the Nile.

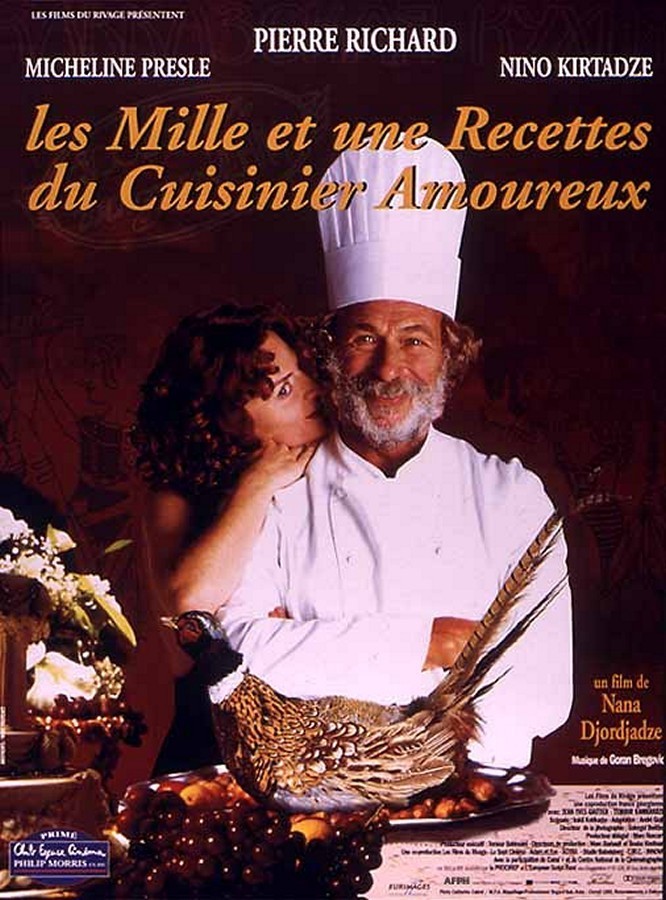

As we meet Pascal, played by Pierre Richard, he is well into his 50s and looks like a cuddly, fuzzy version of Peter Ustinov. He enters the train compartment of the beautiful Cecilia (Nino Kirtadze), smiles, uncorks a rare vintage, and offers her a glass. It is her favorite wine. He asks for five minutes to prepare something to go along with it. She steps into the corridor for a cigarette. When she returns, he has laid out a feast of hard-cooked eggs, cheese and fruit, presented on fine china; apparently he assembled it from ingredients in his valise, or perhaps, like all great chefs, he always has a meal in his pocket.

Pascal’s story is told in flashbacks, after Cecilia’s son, an artist, is given his mother’s journal. In it she describes the great love of her life. She was in her 20s, much younger than Pascal, when she met him, but she identified immediately with his passion, which was not so much for food as for all the things of life: sex, music, art, living creatures. For love of Cecilia, he remains in Georgia and opens a restaurant, which thrives until the communist takeover in the early 1920s, when he has to turn it over to the state and move into an attic room that is virtually a cell. (Cecilia is forced into a union with the piggish local party chief.) What rings false about this scenario is the likelihood that the new communist bosses would have put Pascal out of business. More likely they would have put him to work cooking for them. Never mind; Pascal, sitting unhappily by his garret window, smells what’s cooking in the kitchen below, is unhappy, and sends helpful suggestions to the chef (who cannot read–but a young cook can, and the recipes are preserved to become a famous cookbook).

Pascal hates communism not on ideological grounds but because it gets in his way. When he and a party chief get into a bitter exchange, a duel results; after considering guns and knives, they end up throwing bricks at each other. The movie is droll about its forms of violence; when Pascal’s enemy wants to murder him, shooting is rejected as too mundane, and the poltroon, having recently read “Hamlet,” decides to pour mercury into his ear.

“A Chef in Love” was Georgia’s entry in the foreign film category of the Oscars, and plays as a hymn, somewhat disjointed, to bon vivants everywhere. It also refers, I imagine, to the decades when it was difficult to get a great meal in Georgia unless you cooked it yourself (Cecilia takes Pascal on a tour of great Georgian cooking in the pre-revolutionary era).

Pierre Richard, best known for “The Tall Blond Man With One Black Shoe,” is convincing here at something that is hard for an actor to do: He really seems to be savoring the tastes and aromas of the foods and wines he loves. On TV food commercials, I’m distracted by the sanitary way the models always eat; food disappears into their mouths and they immediately smile, but they never seem to chew or swallow. In addition to his other joyous qualities, old Pascal is an enthusiastic masticator.