She leads a grim existence as a factory worker. Her husband has been hit by a motorcycle and is laid off with a broken leg. Her brother-in-law spies on her and her mother-inlaw spits on her. She’s been diagnosed as a tuberculosis victim and sent to a sanitorium in the mountains, courtesy of the National Health Service. And now she has met a young man who is desperately in love with her, and she finds she loves him too. “We must try to keep our heads,” she tells him, clinging to him. And then after a pause: “But WHY must we try to keep our heads?”

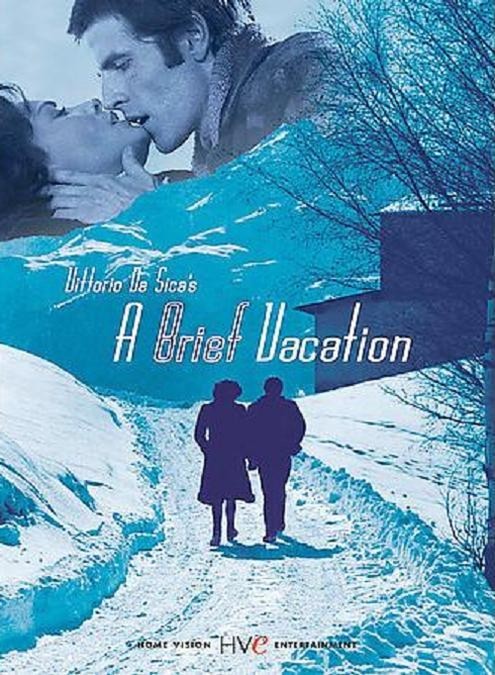

That’s the question asked and never answered in Vittorio De Sica’s last film, “A Brief Vacation.” De Sica, who died earlier this year, was one of the great directors of the postwar Italian neorealist movement, which represented a large, loud break with Hollywood tradition and dealt with life as it might exist outside sound stages.

In movies like “Shoeshine” and “Bicycle Thief” he told the stories of poor people trying to survive in a system geared up to manhandle them. His films grew slicker and more commercial by the 1960s, but he never lost his gift or his heart, and there were masterpieces like “The Garden of the Finzi-Continis” (1972) and now this final return to a working-class subject.

It’s not a movie, though, that offers solutions to the problems it sees; de Sica’s communism was outworn long ago. It’s a love story, a very brief and poignant one, surrounded by a lot of anger. And it’s a “woman’s picture” of the new sort, the kind in which women make up their own minds and make their own mistakes. His heroine, Clara (a luminous performance by Florinda Bolkan), is harassed and bone-tired and driven to shouting things like “I’d do better as a whore” while she faces the bathroom mirror at dawn. But she has resources she never dreamed she owned.

De Sica quotes Appollinaire: “Sickness is the vacation of the poor.” That’s the case here, and as the doctor tells Clara of the spot on her lung and prescribes a month or two in the mountains, the faces of her family shrink into meanness and envy. There is the thought, never quite spoken aloud, that her duty as a wife and mother is to stay in Milan and die. But she packs and goes. “Not for myself, she tells her husband in the middle of the night, “but to protect the children.”

We realize within the first half hour that Clara is an intelligent woman living a life that makes few demands on intelligence. On the train she meets others going to the sanitorium, and they’re all better off than she — a rich man’s mistress, a “performer” — but almost from the moment they meet her they identify with her strength. She has coped with conditions of life the rest of them can hardly imagine, and they have left her shy in this new company, but her friends respond to her resiliency and her character.

The sanitorium is like a holiday. People like her and the food is good. When she meets the young man, it is for the second time; on the day she collapsed at work she met him at the clinic. They went next door for a coffee and discussed their jobs. His was a good one at Olivetti, but he had to bend over all the time. She was seen in the cafe and her husband was informed. When she returned home, tired and sick, he slapped her. “Our love began with my husband’s slap,” she tells the young man.

Their affair lasts only a moment. On Wednesdays the patients are allowed to go into town. They have talked once or twice, and now they come into each other’s arms and make love urgently and immediately. Then they talk and dance and he asks her to run away with him to Germany. To get a divorce. “The poor cannot afford a divorce,” she says. “And what of my children? Shall I throw them out?”

The love affair, her brief vacation, causes big changes in her ideas about herself. The other women tell her she’s really pretty, that she should do something about her nails and learn to walk differently. She was always beautiful and now she allows herself to seem so. And her mind wakes up. A few paperbacks had been left behind by a former patient and she reads them. “Who’s reading this?” her husband asks during a visit. He is the kind of man who puts on his jacket as if he were lifting weights. “I am,” she says. “You learned to read?” “I remembered. It was slow at first but now it goes all right.”

This is a woman who tells her husband it will take the police to get her back to Milan, but at the movie’s end we’re not told what she will finally do. We have a notion. though. and we’ve met a tough, beautiful person. For the screenplay of “A Brief Vacation,” de Sica returned to his old collaborator Cesare Zavattini, the man who wrote “Bicycle Thief” and “Shoeshine.” It’s as if, at 73, he wanted to touch base again in case this was going to be his last film.