“32 Malasaña Street” is better at an abrasive cut than it is scaring you, even though you’d think that such an editing knack would come in handy for a horror movie. Instead, director Albert Pintó powers his story of a family in a haunted apartment with a lot of predictability, but spikes the story every now and then with WHOOSH! a dress being dropped to the floor, or BANG! a cut to someone polishing a hood ornament. When it comes to the tried-and-true horror, the movie falls back on the obvious, and later, the offensive.

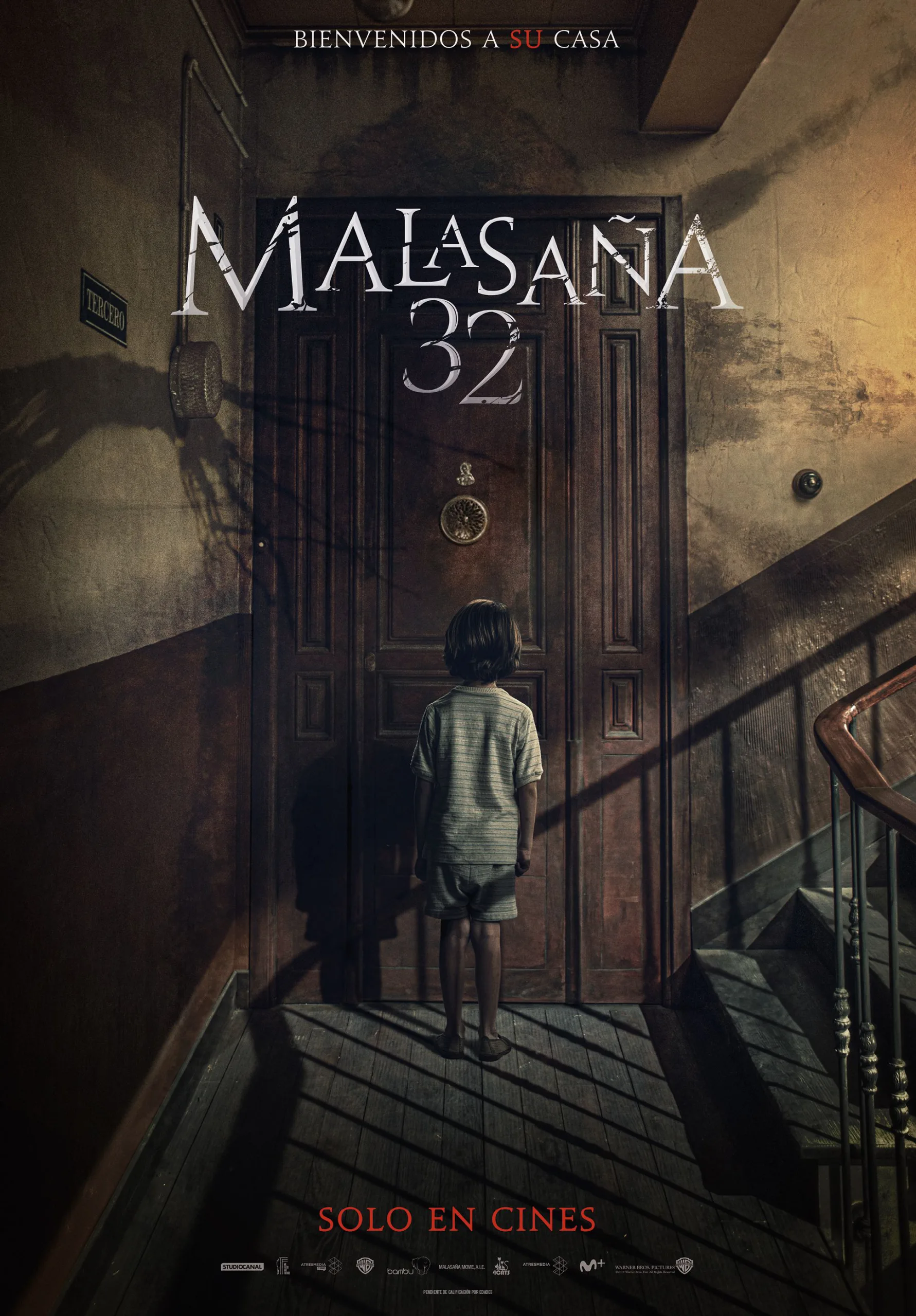

Set in 1976 Madrid, the story focuses on a family that has moved from the village to the city, a controversial choice given that the family is struggling with money. But the Olmedos want to make it work, and they’re unaware of any spooky business that happened in the apartment before (some of which we see in a mildly unsettling opening prologue, involving two boys and an unresponsive old woman). While the parents Manolo (Iván Marcos) and Candela (Bea Segura) try to make money after such a move, the oldest sister Amparo (Begoña Vargas) watches over her two brothers, the lonesome Pepe (Sergio Castellanos) and antsy Rafi (Iván Renedo). Rafi is a wide-eyed five-year-old who is stuck sleeping in the same bedroom as Grandpa Fermín (José Luis de Madariaga), and who starts to see and hear creepy things at night in the apartment. The story claims to be inspired by real events, but it’s more believable when you look at it as “inspired by James Wan’s ‘The Conjuring.’”

None of this is notably original, and it’s the kind of movie that to give away its cliches would spoil many of its major plot developments. This becomes a problem in particular with the central spooky scenes, which try to lock us into the perspectives of its progressively frightened family members as they carefully tread through dark rooms of the apartment, while the camera matches their gaze of looking in one direction, slowly to the other, and then back. “32 Malasaña Street” is initially effective with this type of unease, but we become all the more aware of the rhythms of its scares. Along with the story struggling to develop beyond everyone learning that the apartment is indeed cursed, its lack of creativity breeds predictable sequences.

The most appealing development comes in midway through, and lasts for only a few scenes. After every member becomes privy to the building’s aggressively shut doors and ghoulish shadows, they run away with no guaranteed housing (consider how the family in Wan’s “Insidious” simply moved to another big house when they had a similar problem). The Olmedos are strapped for cash, with jobs they must get back to. It’s in these brief moments that the movie hints at a deeper horror, of not being able to provide for family, and has a better use for the care that it does make you feel about the Olmedos. The performances are better here in these flashes too, whereas they’re usually left with trembling hands and nail-biting, trying to force a sense of discomfort during Pinto’s dull, screeching scenes.

“32 Malasaña Street” quickly drops this plot point about money and makes things worse for itself. In need of some left-field twists to bulk up its third act, the movie manages to provide offensive portrayals of both disabled and transgender people, presenting their othered identities as either magical or monstrous. It’s telling of the movie’s rote nature that these are the tale’s only standout elements, and that in its reliance on horror mainstays, it uses representation that good modern storytellers have long distanced themselves from.

Now available on Shudder