A big part of being a teenager is anxiously waiting to be an adult. The eighth graders who dominate the screen-time of “18 to Party” know this, as they hang outside a nightclub that a batch of older teens are admitted to. It’s worth wasting a full afternoon just to try to get in, to get a glimpse of the freedom in being slightly older.

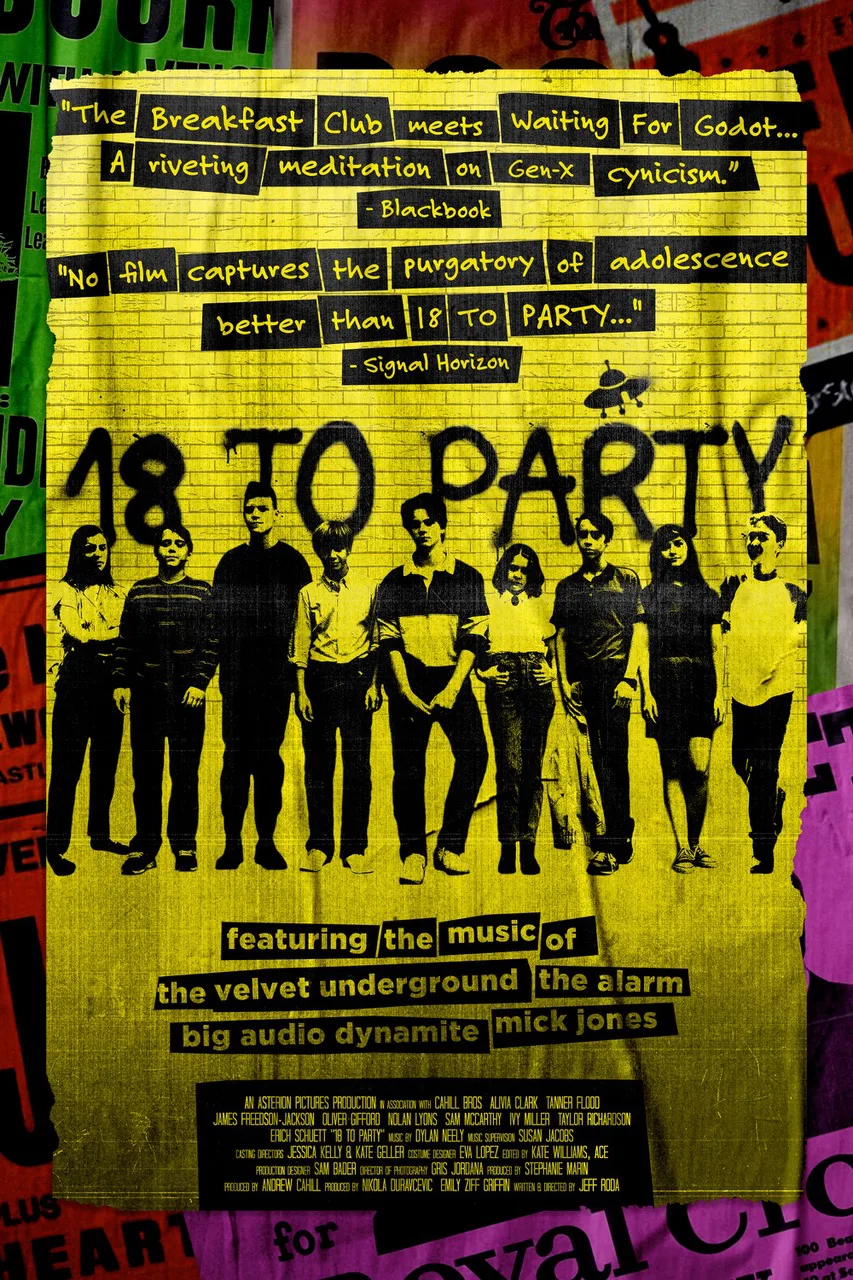

The year is 1984 and the paradise is a small nightclub, one that emits copious amounts of smoke and jangly guitar riffs whenever its door is opened. But this stand-and-talk movie from writer/director Jeff Roda is about the back of line, which is more of a back lot, and is populated by eighth graders who can’t get in just yet because they’re too young. There’s the geeks, like Dean (Nolan Lyons) and Peter (Sam McCarthy), who kick off the movie by arguing about technology. And you might categorize Missy (Taylor Richardson) in such a broad group too, as she doesn’t understand her recent social status downgrade (her “friend” used her for a ride and ditched), and listens to U2 on her headphones.

And then there’s the freaks, like Kira (Ivy Miller) and the mostly silent James (Erich Schuett). Both of them hold an angst against society and Ronald Reagan, while graffiti saying “BEAT THE RICH” is their initial backdrop. Kira in particular is glued to a newspaper she digs out of a dumpster. She doesn’t hesitate to get in anyone’s face, and she lashes out at the others by deigning them “pop tarts.”

It’s a lot of characters—arguably, too many—for a story that doesn’t take them to surprising endpoints, and doesn’t challenge our ideas of high school stereotypes, in the movies or in real life. On top of that, the movie makes the bad choice of teasing us with glimpses of the older kids, who get the glory of waiting in line. Sometimes Roda uses their presence for interstitials, introducing them as they walk up to the line, or later filming them in slow motion (accompanied by The Velvet Underground’s “I’m Set Free”). But these are misleading—we don’t get to know who these former eighth grades are aside from their outfits and hair styles. And in the story’s tedious Waiting for Godot fashion, we don’t see the inside of the club either. These older extras show off a detailed production design that conveys the period of 1984, but it becomes a distraction to the story as we continually wonder what fun they’re having.

Roda’s script is relatively unfocused in building energy, but one character seems to be a priority, the strait-laced Shel (Tanner Flood). He wears pure white shoes to make a cool impression with his peers, and is under a negative influence from his slightly older, very pushy friend Brad (Oliver Gifford). Shel is best as a relatable, clueless eighth grader—it’s funny when he has qualms with failing a pop quiz by getting a “three out of five” (“That’s almost next to perfect,” he reasons with honest eighth grader logic). But “18 to Party” points him toward his interactions with Amy (Alivia Clark), a classmate and crush trying to get him to take drama at school. It’s an earnest subplot, one that even takes the action away from the backlot to a construction site at magic hour, but it does not liven up the screenplay.

“18 to Party” is too stagnant for a story about young people wanting to break free, but it does have a few inspired notes with the larger adult ideas that the kids just don’t understand. There’s talk of a possible suicide pact in the town, and a UFO sighting that seems to have captivated many of their parents. Their conversations touch upon trying to understand these bizarre mysteries, but the subjects always remain far bigger than them. Like when they hear loud excavator machinery just over the parking lot fence, and look up at it as if they’re in a Spielberg movie, there’s a palpable sense of wonder.

And then Lanky shows up. Played with refreshing looseness by an excellent James Freedson-Jackson, he pops in and out of the movie as this traumatized stoner who has been designated to a mythical status, needing professional mental help after his brother’s mysterious suicide. It all makes the kids uncomfortable to talk about, and even more uncomfortable when Lanky appears, ready to party. Lanky has a heartbreaking, fascinating monologue later that reminds one of how much the power in young performances is about watching young ones deal with adult emotions we might recognize, but that they do not. Freedson-Jackson’s take on Lanky is that his brother’s suicide is so wild that he has to package it like an unbelievable joke. It doesn’t matter that Lanky is stoned while he conveys it—through Freedson-Jackson’s excitement and intensity, you can see just how messed up this kid already is.

“18 to Party” leaves the viewer wanting more from writer/director Roda, like for him to push his young performers to think beyond their stage directions, or to give this movie the imagination it so needs. Take a moment about 20 minutes in, when Rizzo, the gatekeeper to this paradise, arrives. He rolls up in a big red muscle car, displaying a great deal of bravado. He’s a small character but his appearance should be a slam dunk moment—maybe a striking camera angle, a particularly in-your-face music cue, an off-hand joke that tells us more about Rizzo. Instead the movie merely watches him cross a parking lot, the camera trapped by using the teenagers’ point of view as they stand away from where all the action is happening. “18 to Party” nudges that there’s got to be something more to a story concerning youth like this, that it can’t feel so limited to what they see and chat about. Otherwise we too are stuck on the sidelines, impatiently waiting for the fun stuff to kick in.

Now playing in virtual cinemas