The documentary series “Wild Wild Country” is more than just the true story of a religious movement (or cult, if you prefer) that created a utopia named Rajneeshpuram in the small town Oregon of Antelope in the early 1980s, setting off a chain of events that must be recalled in detail, from both sides of the issue, to be believed. On a wider scale, it’s an all-American story of faith and fear, conservatism vs. liberalism; of biochemical warfare, blended beavers and so much more. (I first reviewed the series in full with no spoilers last month; click here to read that.)

If you have seen even the first ten minutes of Netflix’s series, you understand what I’m alluding to, and know that the addictive quality of this six-part documentary comes from the questions it raises more than the promise of answers. As someone who has now seen the series twice through, and tried to recommend it as succinctly and often as possible (“terrorist sex cult” is a good elevator pitch), I wanted to engage the directors of the series (Chapman Way and Maclain Way) about my many curiosities with “Wild Wild Country,” including how Netflix got on board the binge-ready series, the current status of the doc’s characters, their filmmaking goal in favoring experiences over cold facts and more. Below is an in-depth interview that has been edited and condensed from our hour-long conversation; spoilers and very specific references follow in the second half.

Congratulations for starting a cult that now includes Chrissy Tiegen, Questlove and my parents.

CHAPMAN WAY: That was the intention! [laughs]

When did Netflix get involved with “Wild Wild Country”? Did they know the binge potential of it, given the recent wave of true-crime documentaries?

CHAPMAN: Basically, right when we started digitizing our footage, only “The Jinx” had come out. It was still pre-“Making a Murderer.” There wasn’t quite this cultural phenomenon of doc series. And so we had kind brief conversations with people who were like, “Yeah, it’s an interesting story, but does it really need to be six hours?” And so we just set off making it on our own, because we knew that if we did this at 90 minutes, it would just cheapen all of the complexities of the story.

It was kind of right around when we were first starting production, by that time we had done a ten-minute teaser video, where we sat down with Netflix and showed them what we were doing. We had done our first documentary with them (“The Battered Bastards of Baseball”), and so we were really familiar with them. They saw our teaser and our treatment and all of our characters and I think they were really excited about teaming up on this.

One of my favorite things about this documentary is that it’s about experiences over facts, these two different sides of this insane story. Was that always the intent?

CHAPMAN: Yeah, I think it’s just what we were excited about as filmmakers. A lot of people watch documentaries because they just want the information. We’re always much more interested in the inner journeys of our characters and letting our characters take you on this roller coaster. We tried to sit back and give our characters as much support as possible through music and editing and visuals to capture their journeys.

MACLAIN WAY: This was kind of the thing, where we didn’t know about Rajneeshpuram. So when we kind of got into it through all this archive footage and realized how amazing this story was, we kind of just did some googling; it became clear to us that things like the criminality and the crimes that happened at Rajneeshpuram were very well documented and well known by people who knew the story and admitted to by people who pled guilty to them. So, very quickly I felt like we weren’t interested in doing a typical true-crime documentary series, even though we love those. We were excited by, “How does this ostensibly peace-loving group who come from India and like yoga and meditation, how do members of this group become responsible for the largest biochemical attack in US history?” We were interested in hearing from the decision-makers and how they felt they were pushed to that. Whether they’re reliable or not is part of the fun of watching the series, I think.

When you’re preparing for interviews, did you ever come across people who might have been lying or who were wrong about their accounts?

MACLAIN: Yeah, well we read probably over 20 books and every single book had incredibly different perceptions, even inside the Rajneesh community. There’s different factions within that community that said it was all Sheela who did everything, or people who believe that the guru was responsible. There’s a lot of different political factions within that movement alone. The people that we interviewed, I took them at their word that this was their experience.

We spent a lot of time with these characters before we even interviewed them; most of them we’d spent at least three or four visits getting to know about their life and getting to know them. That said, I do believe they were telling us the truth [but] they do obviously have clear agendas in what they are hoping the audience will take away. We’re not naive in saying they don’t have an agenda—Sheela has a very clear agenda, the lawyer has a very clear agenda, the people of Antelope have a very clear agenda. But for the most part, we took them at their word for what they were saying. I think the tragic thing is that this how they all truly feel about the story.

It’s interesting that you use the words “characters” to describe these non-fictional people in your documentary.

MACLAIN: Yeah, we’ve always kind of talked about them as our cast of characters, and I think that we’re really interested in characters that are three-dimensional, and have their own agency. We’re not just putting them in this box to satisfy our needs as documentary filmmakers, but letting them flesh out their own stories.

How easy was it to find these people, your characters?

MACLAIN: Tracking them down and locating them wasn’t too difficult. There was a lot of initial skepticism on both sides when we would track down the people, from the Sannyasins’ point of view, they felt like they were really burned by the media and were always referred to as this terrorist evil sex cult. And then on the other sides, the Oregonians were like, “We were always portrayed as these super racist, bigoted people, but we had legitimate concerns and fears of this group.” So it was just kind of working past those initial misconceptions, and once we said that we were interested in exploring these complexities, “We’ll let you speak, we’ll give you a platform to tell your truth,” I think they really ended up deciding that this was an important American story that shouldn’t be forgotten, and they both saw it as a warning sign for different reasons.

It’s interesting that you mention about the 20 books you read, because it brings up the question of what was left out. But there’s the New Republic piece by Win McCormack that came out and others, so I’m curious about what you wanted to do when it came to the more insidious elements of the Rajneeshees.

MACLAIN: For sure. Win was kind of hard … we reached to him two or three times to get him on camera, and we couldn’t quite get him to fit us into his schedule, type of thing. So, I think now that it’s a well-known Netflix documentary series, he’s more interested in getting that out, which is his right to do. I think at some point most of that reporting was based on [the Indian commune before Rajneeshpuram] Poona One, and our story was a bit more Rajneehspuram focused. And I guess we had felt like we had covered that the Rajneehsees had assassination conspiracies to kill political appointees and government officials and an investigative journalist and that they had poisoned 700 people. I read Win’s article quickly, I wish I had given it a longer read, but I felt like we had covered more of the crazy criminalizes. but I’m sure it did happen that some Sannyasins sold drugs in Poona One, I just didn’t know how tame those felt by the bizarre, over-the-top criminality that did happen in Rajneeshpuram.

CHAPMAN: You just rely on what people tell us on camera, like we had Les Seitz of The Oregonian. I think had Win accepted our invitation, we would have had no reason to hide that. We just rely on what people tell you.

The truth is that we talked to a lot of ex-followers, and they said the same thing. That if you weren’t inside that power circle of the 10 to 15 people that Sheela commanded, “we were naively obvious to what was going on.” We thought that was tragic too, that a lot of people who joined this movement for the right reasons and kind of this Herculean effort to create their own happiness in their own community.

What are your emotional feelings about that, especially within the second episode when the Rajneeshees think they are creating their own utopia?

MACLAIN: I think what was interesting was that when Bhagwan had taken a vow of silence, and what I had gotten from them, is that their life had become much less about their devotion to Bhagwan and more just about the sense of community and family that they felt there. Which is what I think drew them so tightly to that community and wanting to defend it.

CHAPMAN: We interviewed a ton of Sannyasins early on, and yes there were some who left with resentment and regret. But I’d say by and large with the people we talked to that they felt like it was the most profound and rewarding experiment than anything they have been apart of, which we found pretty rare. When most cults implode it’s with hate and resentment.

When talking with the Oregonian side of this story, did you get a sense that people had thought about this for a long time? Or that they were dusting off these memories? Especially concerning people who had gone through this experience and then it vanished, only for you to bring it up decades later.

MACLAIN: I think that most of the people we talked to in Oregon, it was from their perspective a really traumatic experience that they went through. I think most of them would like to have believed that they’ve moved on, but as soon as we started talking to them it was clear that a lot of them haven’t really moved on. We wanted to dive into why that was.

When you get to the editing room, how do you distance yourself from the personal connection you’ve had with these people, so as to be balanced?

MACLAIN: We never tried to be objective for any journalistic, righteous way. We were making a series that the narrative has to work in a certain way, so our concerns are, “Are people going to keep watching this, is it interesting, is it provocative?” We kind of found this rhythm in the editing room, it was working for us and didn’t know if would work for an audience. But we really enjoyed getting to hear someone’s perspective. We spend ten minutes with this character, and then boom let’s do this 180-degree flip and show the complete opposite perspective and force the audience to do some real critical thinking to see “Where do I really feel about these issues? How do I really feel about freedom of religion? How do I really feel about gun rights?” We were just interested in the idea of you getting to see the humanity of one side, and then flip the POV and you’re gonna hear from a different perspective. That was exciting for us cinematically, and intellectually.

Where does the reward come from for a documentary that is meant to ask so many questions? Have you been paying attention to a lot of reactions?

MACLAIN: It was about four years ago since we started first digitizing the footage, so any time that you dedicate your life to something like that, we’ve definitely been interested in hearing the reception. And in kind of a large way, we edited this whole series in the bedroom of the Duplass headquarters, and it went from small and launched globally which feels great. But the reward comes from watching people really engage with it. To be honest we were always a little bit terrified that this documentary would come and go as just another documentary series; Netflix does a lot of content and not too many people remember this story. So there was always this fear in the back of my mind about whether this would be a story that people would want to press play on, and episode one is just kind of setting up the chessboard. There’s not a lot of crimes and poisonings and attempted murders, because we really wanted to set up these characters and what their intentions were. We were a little bit worried about those decisions, but still confident that we made the right ones.

It’s a very active experience for the viewer, especially how much your a viewer’s opinion changes throughout the documentary.

CHAPMAN: And that’s kind of what we pitched Netflix on. We said, “This is not true crime, this is for mature adults who can think on their own and make up their own decisions. We’re not going to spoonfeed anyone, they’re gonna have to dive into it.” They were really into it.

Even Netflix’s “American Vandal” has a sincere, winding arc that takes you to unexpected places.

MACLAIN: I thought it was the best show of last year. We were in the middle of editing and I was like, “Can I watch this? Is this gonna hit too close to home?” It was so well made, we were just dying.

With regards to very specific characters from the documentary: did you talk to Krishna Deva?

MACLAIN: He was the biggest character that we desperately wanted to interview, and we just couldn’t get him. We got him on the phone twice for like five seconds each, when we were doing our interviews and he made it very clear to us that he had no interest in reexamining it, and was just never gonna do it. We tried emailing him a few times, and I heard from a few Sannyasins that he had a tough go and spent a few years in prison. I hope one day he does talk because he worked right under Sheela, and has some incredible insights and facts to what actually went down.

He seems to be someone who encapsulates the macho hippy idea.

CHAPMAN: It’s really interesting; Sheela would come down really hard on him because she thought that he was being too soft in the beginning, because he was trying to reach out a lending hand to Antelope and trying to compromise. And the story is that Sheela took him to Bhagwan and told him what was going on, and Bhagwan told him he needs to be a lot more forceful and a lot stronger, and that you can’t let people push you around. And [Krishna] turned into this provocative personality who was really threatening.

Sheela is such an enigmatic figure. What was her presence like in person?

CHAPMAN: We had done interviews with Oregon federal officials and this was a woman that they told us was quote-unquote pure evil. And we had digitized the archive footage and saw her on “Ted Koppel,” “Crossfire” and with Pat Buchanan, just eviscerate these male journalists. So we were a little timid to go fly out and talk with her but as soon as you meet Sheela now in modern day, you see how witty and charming … she’s a really strong personality, she’s still feisty. The truth is that we interviewed her over five days, and the first day was just kind of average material, we were just going through her background, she didn’t seem to have a lot stakes in the story. Whenever we would kind of push her on something she’d be like, “Oh, that was 40 years ago, a different time in my life.” But after day one, Mac and I decided to show her a lot of the archive footage that we had, and it was footage of Antelopians saying pretty prejudicial things, and the government officials really going after them. There was something about her watching this footage that just kind of reignited this passion inside of her, and the next four days she came into that interview room with something to prove. And the whole interview was different from then on out, and she was a different person. It was fascinating to see that transformation and see how this old footage brought up all these old emotions in her.

Our takeaway is that she’s like everything in the series; she’s a little bit terrifying, she’s kind of charming, she’s incredibly compelling. But she’s also really smart. I think a lot of Americans hear people who speak foreign languages and hear broken English and think they’re not that smart, you know? But Sheela’s brilliant, and in getting to know her she’s a fine artist and she studied art in college in New Jersey, and does these amazing paintings; she’s a cinephile who loves Fellini movies you can talk to her about Fellini and Italian neorealism. It was such a dynamic documentary character.

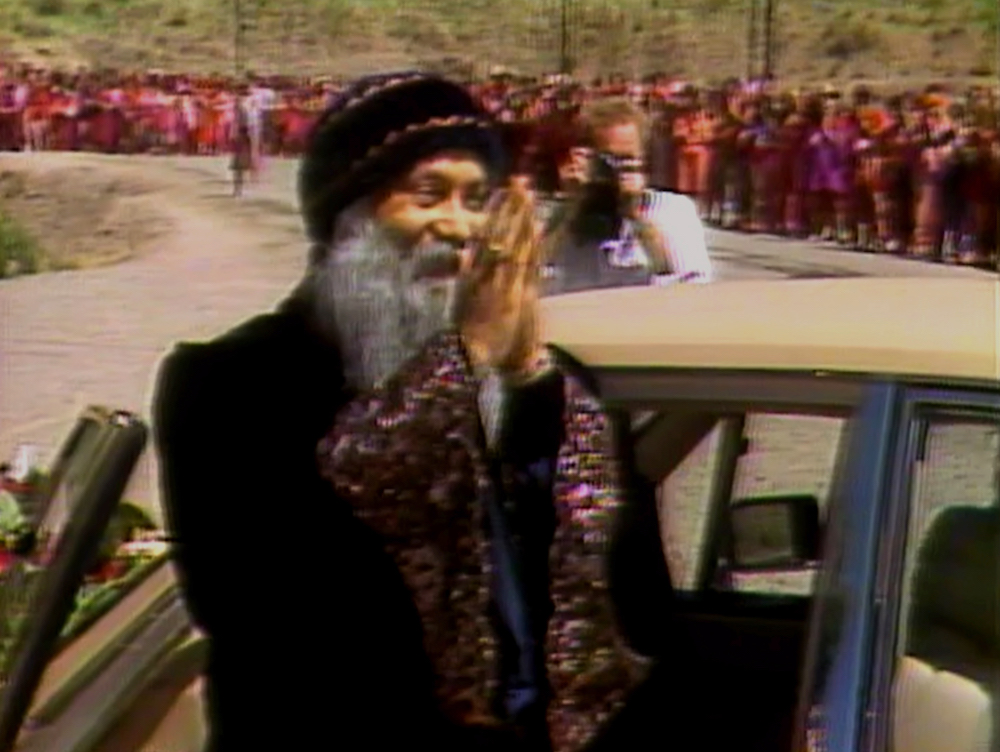

We’re talking about all of the interviewees, but Bhagwan is kind of the mysterious center. What kind of image of the Bhagwan did you get through everyone that you talked to?

CHAPMAN: It was really interesting, that with the followers we talked to, their devotion to him and their love to him was something you couldn’t intellectualize, or explain to someone. You just have to take them at their word that they love Bhagwan the way you love a family member. He was pure love and acceptance for a lot of these people who had come from difficult backgrounds. The truth is that his teachings and philosophies are a little vague and ambiguous, he stole from a lot of Eastern mystics and married it with Western capitalism and made his own brand of spirituality. There wasn’t a lot more to it than that, and he created his own meditation techniques, and what we found is that most people who joined felt like they belonged to something that was bigger than themevles.

The biggest takeaway I found is that he really is whatever you project onto him. If you’re from Oregon and you think this man is evil incarnate and is brainwashing people and hypnotizing people, you’re going to project this fear and this thing you don’t understand and these thoughts and emotions on to him. If you’re a Sannyasin, you’re going to project as well. He didn’t really even speak for much of the story, which I found so fascinating that everyone would come to their conclusions about him. He was kind of like Oz, the man behind the curtain. We wanted to keep it that way, for us he was more interning as this Oz character that you don’t get to know.

There are entire episodes in “Wild Wild Country” where you don’t hear from him or see him, even though he is interacting behind closed doors.

CHAPMAN: I think we really wanted to save it for when he breaks his vow of silence and really goes after Sheela, which was so interesting to us. Because when we talked to Sannyasins, they all said that this was going to be the big moment. And then he comes out and is like, “That bitch Sheela did all this stuff” and I think it was a shocking moment for all these Sannyasins.

With its ideas of faith and leadership, your series reminded me a lot of Paul Thomas Anderson’s “The Master” and Philip Seymour Hoffman’s own guru, Lancaster Dodd.

CHAPMAN: It wasn’t something that we were going back to when we were editing, but I think there are a lot of similarities between these charismatic leaders who are intelligent. They have a vision for something grand, and how they’re able to use a lure to pull to people into their orbit.

MACLAIN: That idea of charisma was something that I would constantly talk to Chap or our editor and producer about. I think that’s why the series came out the way that it did, because we would play devil’s advocate, but I don’t think we were purposely doing that. Sometimes our own positions would evolve as we made the series, but charisma is an interesting idea because I think people would talk about meeting Obama or JFK, when this guy entered the room there was something about him, whether that’s inherent or projection. With Bhagwan it’s the same conversation: is charisma something that people have, or is it all projection? I think it could be a combination of both.

Did you have any footage that you wanted to get in “Wild Wild Country” but didn’t make the final cut?

CHAPMAN: There were two sections. One was when the guru left the United States in 1985, I think he tried to gain admittance into over 27 countries and no country would allow him off the tarmac. They called it like a world tour, he went to places like Greece and Uruguay, and the US was calling up these countries and putting pressure on them. We had all of this footage of these governments denying him entry, but episode six was getting so long that we had to cut it out.

And then the second section that we cut, and maybe we can put it on a DVD special, is that we had this “day in the life” section where we had the Sannyasins walk the audience through what a day was like just being in the commune. Separate from all of the political and cultural battles, what was it like waking up and having breakfast and going to work department and working with your friend in the farms, or legal departments, and then they’d have dinner and go do their meditation practices. It was this kind of real, magical summer camp for adults, and the footage is really cool. I think people who like the series would be interested in what an average day is like for a Sannyasin.

The ending is striking, where you see that the following is even bigger; how did you want to approach that, especially when viewers are watching this story about this great leader and this utopia, and think, “this Osho thing might be right”?

CHAPMAN: The first thing that we found interesting is that we assumed coming into this story that most people aren’t familiar with it, and they would think “I’m not familiar with it, therefore it doesn’t exist anymore.” It was fun to play with that concept knowing that in episode six it would be a reveal to say that this guy and this movement, they still have communes all over the world. It’s big in Brazil and big in South America. Mac and I visited the Italy commune in Tuscany and spent a week there. They still have all these satellite communes dedicated to his teachings.

The other thing is that there’s a fine line in that you’re not trying to be a champion, or sell Osho to the audience. But at the same time, it is an interesting component that it is bigger than ever. And for some, that might be terrifying, that this thing has grown and spread. I think for another kind of audience, it’s an interesting takeaway for them that they can be a part of it if they want to.

Do any of the Sannyasins that you talked to still practice?

CHAPMAN: Philip, the lawyer, [he] still practices and still goes to India once and a while. He still very much considers himself a devotee of the guru and of his beliefs. Sheela is somewhere in the middle, where she’s not a part of the community anymore—she’s been excommunicated. But she still very deeply involved with Osho’s teachings, she does a lot of the same meditations that Osho taught with her patients now. And then our third main Sannyasin character Jane is totally on the opposite side of things. She very much believes that she was part of a destructive cult that did a lot of damage and is now in the process of rehabilitation and refining her identity.

Do you know the status of Philip’s book?

MACLAIN: I don’t know; he’s been working on it for a long time. He seems to be really excited that there’s a platform and audience for his book. He has a lot of incredible memos and paperwork, and he believes he has a lot of evidence that shows this prejudicial bias of our government to get his guru out of the country.

And lastly, there’s the smiling Oregonian with the glasses and the overalls …

MACLAIN: Ron Silvertooth.

What’s his deal? Does he have a Rajneeshpuram gift shop?

MACLAIN: That interview was taken inside what they call the Antelope Museum. There’s only 50 residents of that town, and they have a little town hall center where they have the memorabilia that Silvertooth has collected over the years. He wouldn’t even show us all of his collection on camera because he was afraid that someone would steal it. He put up the t-shirts and the poster that he found in the garbage. And then he asked me if we knew anyone who would want to buy the poster for $5,000. I told him I would ask around, but still haven’t found any buyers.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.