Let me tell you a fairy tale. Two brothers

are raised in a house with big windows, under the care of a man. They can look

at the world outside but never go outside and see it. The man says he’s keeping

them safe, and he tells the boys everything there is to know about the world

outside: the color of plants, the sound

of the wind, the shapes and sizes of objects the way people behave, and the way

emotions feel and what they mean. The brothers are intrigued by the man’s explanations,

but they can’t help feeling there’s more to the world than what the man tells

them. One night, while the man is asleep, the brothers look closely at him and

discover that his skin is made of wool, like a sweater. They find a loose

thread and pull, revealing a whole universe in miniature inside the man’s

stomach. But it’s different than how the man described the world to them, and

looks different than the one outside their window. Shapes are different, sounds

are louder and quieter than the man described, and plants don’t look like they do out

the window. In here, inside the man, everything is twisted up and strange; everything is beautifully ugly; every color is more vivid. Instead of people there are puppets. The brothers look into

the eyes of the puppets and suddenly they knew everything about humans and

more. The puppets taught them everything there was to know about people, things

the man never bothered trying to explain.

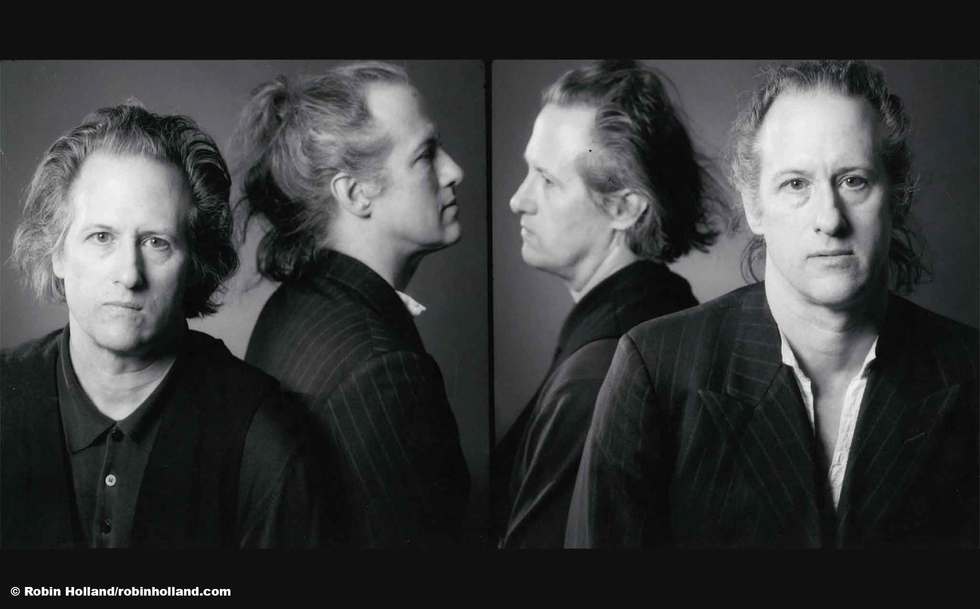

This is the story I’ve always told myself

about filmmakers/animators/magicians Stephen & Timothy Quay. How else to

explain their inhuman intelligence, their avant garde rhythms, that they were

able to conjure a universe so alike and yet so completely different from our own.

So gorgeous, yet so horrific. So fantastic, yet so grounded in the tactile

realities of human, plant and animal. Since their debut in 1979, they’ve slowly

come to infect our reality with the influence of theirs. They reached into

fairy tales for inspiration and, pulled out a secret aesthetic history of the

world that only they could see. They’re lovingly, painstakingly crafted short

films have influenced everyone from Tim Burton to Terry Gilliam to Christopher

Nolan, who has bankrolled an awe-inspiring 35mm retrospective of some of their

major works currently playing New York’s Film Forum. He’s also completed a

short, sweet documentary on the brothers (simply called “Quay”), filming them

with a 35mm camera in their home studio, the first time the director has shot

one of his own movies since his 1998 debut “The Following”. That is the kind of

affection and dedication the Quays inspire. Right now in film schools across

the country there’s one kid in class whose favourite film is “Street of

Crocodiles”, and though she may never have the success of the Kubrick or Leone

fans, she’ll tug on the sweater that conceals reality until she really

understands the way art can unearth the secrets of humanity.

I interviewed them at Film Forum and they

tell me they’re always after “elusive forms” and that puppets offer a way into

a “contemplative realm,” adding a little weight to my fairy tale. Everything

about the Quays is distinct, from their surreal backdrops to their spindly,

whisper-soft voices, to the way their camera moves. The American-born,

England-educated identical twins speak in a splendid hybrid accent, and the way

say the word “puppet” is completely unique. Once you’ve heard them talk about

their “poppits,” you’ll never forget it. Apt, because those puppets are what

people will remember first when they hear the word “Quay.” “The eyes are the

soul of the puppet” one of them says, early in Nolan’s film. That’s why the

brothers coat their puppet’s eyes in olive oil, to keep them shining and

looking right back into the viewer’s soul. One of the many special touches that

only the brothers apply to their work. In conversation with Nolan on Wednesday

night (who has used Quays’ films as visual inspiration for his own work), at

the very start of their retrospective, the brothers outlined some of their mad

method: Keeping cameras aimed at mirrors pointed out their studio window for a

full day to capture light just right; having to move the dolly and shift focus

imperceptibly a hundred times over for a few seconds of camera movement;

cutting the top of a doll’s head off to fill it with straw in order to let

light come through the eyes with the right intensity. Happy accidents were

their masters, influencing and changing their films for the better at every

turn. Anyone who’s seen their films knows that every accident made their work

that much more special. “In Absentia”, a work commissioned to compliment a new

piece of music by Karlheinz Stockhausen didn’t appear to fit the music at all,

until they moved it 25 seconds to the right on their editing bay. Suddenly, it

made sense. The German composer had only one note for the brothers when he saw

the finished product. “You know guys, I’d like a little bit of blue…somewhere…”

They looked at each other for a long moment, trying to figure out how to

respond to the mad genius standing in their studio. When he left they happily

obliged, adding some to the end credits. Another happy accident.

What scares the Quays, they who seem to

write our nightmares for us? I was curious to know after having been watching

their work since I was a teenager. “Other than losing your teeth?” They both

laugh. They always laugh together in our short conversation. “Violence.

Unacceptable violence. You know that it can happen so quickly…” Which is why

they steer away from it in their films. “What we value in other people’s work

is that sense of genuine disquiet and unease. You accept violence in Hitchcock,

but what we prefer is a malaise. This feeling that’s underneath you, behind

your back, it’s the undertow.” Pressed for a modern example, they come up with

season 1 of True Detective. “It’s a very subtle language and we admire it

because we have no desire to be violent in our own work.” They also fear for

the future. Though they’ve worked beyond puppetry, designing theatre, ballet,

opera and most recently a video game. Unfortunately, it’s on “pause.” “The

money ran out.” They offer, clearly disappointed. It would have been a

marvelous opportunity to see what these old school storytellers could have

done. “We won’t do CGI.” Their latest project is a feature length movie based

on Bruno Schulz’s “The Sanatorium Under The Sign of the Hourglass” (which would

be 75% animation and 25% live action). They’ve built some of the puppets and

sets and they’ve shot 20 minutes of it, but need funding to finish it. ”You

have to pay for the studio or we’ll lose everything. The freedom to make this

kind of thing. It’s an urgent concern. You’re on the edge of eclipse.” Says

Timothy, but Stephen corrects him. “Extinction.” If every filmmaker was as

forthcoming as Nolan about the influence the brothers have had on their work,

they wouldn’t need to worry about money. Just one gesture in particular, of a

fluttering motion of body parts, so fast they appear to be caught between

dimensions, has been imitated more times than one could reasonable count.

Hopefully the retro and the beautiful documentary will rekindle interest in the

humble geniuses. I like to think we’ve earned the gift of a Quay feature, and

they’ve more than earned the money to make it. They only expanded the

definition of animation.

Their world is born of endless, ornate

invention. Every frame is packed with singularly creepy and gorgeous detail.

Schulz, who provided the inspiration for their watershed “Street of

Crocodiles”, talked about the essential poetry of the everyday (“Honor the

marginalia, is what we’ve always said.”), and that’s precisely what the Quays

manifest. The simplest colors, plants, shapes, textures and ideas are combined

in shocking ways. The inch of dust and gold-hued mildew that grows on a mirror

suddenly becomes part of the way their characters view themselves, and by

extension the world around them. Signs of age, of a past life for every puppet,

are a form of respect, they say, to the original, anonymous creators of the

objects they repurpose. The Brothers see the work of thousands of long-dead

unappreciated craftsman as essential to the human experience, and by thrusting

them together, giving objects like screws, combs, ladders, and pencil tips the

same life that Walt Disney gave his talking animals, they honor the efforts of

every architect, factory worker and machine shop hand who never got to sign his

name to the products he created to help the world move forward. The eyes are

the soul of the puppet, and the films of the Brothers Quay alert their audience

to the soul in every discarded, forgotten object. They see what few others can,

they see inside the heart of a man-made world, and to the rest of us they relate

the secret information to which they’ve become privy. Their perfectly crafted

fairy tale world mirrors ours and helps the rest of us see the beauty all

around us.