CANNES, France, May 10 — How to have lunch at the Cannes Film Festival:

I was scheduled to meet playwright and movie director David Mamet at 2 p.m. on the opening day of the festival in Room 138 of the Carlton Hotel. I knew he would be late, because I had just come from the press conference after the morning preview of his new movie, “Homicide,” which was chosen to open the festival.

Mamet’s movie stars Joe Mantegna as a Jewish cop who doesn’t think he quite fits as a Jew, or a cop, and stumbles into a homicide that may have anti-semitic undertones. There was heavy sledding after some of the questions, including one from a man who claimed to have been attending Cannes “since Armistice Day 1918” and another from a woman who asked about his “theatrical dialog.”

“Theatrical?” Mamet was saying as I shouldered my way out of the press conference. “That’s the dirtiest word in the movie industry. I write the dialog the best way I know how.”

I had to leave early to be on time for the luncheon appointment, so I shouldered my way out of the press conference and walked down the Boulevard de la Croisette, my shoulders hunched against a mean wind that was blowing in from the Mediterranean. In front of the Carlton I paused to examine the facade, which again this year has been rented out to movie posters. There was a big one for Mickey Rourke and Don Johnson in “Harley Davidson and the Malboro Man,” and I reflected that it wasn’t everywhere in France that they could spell Harley-Davidson but not Marlboro.

There was no answer when I knocked at Room 138. No problem. Mamet was still at the press conference. I sat on the stairs. At 2 p.m. promptly, a room service waiter arrived with four sandwiches and two big bottles of Perrier. He knocked on the door. No answer.

“I’ll sign for it,” I said. “I’m meeting some people in Room 138.”

“Mais, monsieur…”

He looked doubtful. We waited. Silence stretched in the corridor like a sleeping snake. He glanced at me dubiously out of the corner of his eye, and finally gave that little French shrug which means c’est la vie, and presented me with the bill. I signed it “Gene Siskel” and added a generous tip. The waiter disappeared.

A journalist from Israel appeared from down the corridor. His eyes lighted up at the sight of me, and he reminded me that we had once had lunch together with Menahem Golan–just the three of us, as I recalled, and 250 other people, in a big tent on the beach. I recalled our meeting fondly, and he hurried off down the stairs.

Silence rolled over on its back and began to twitch its tail.

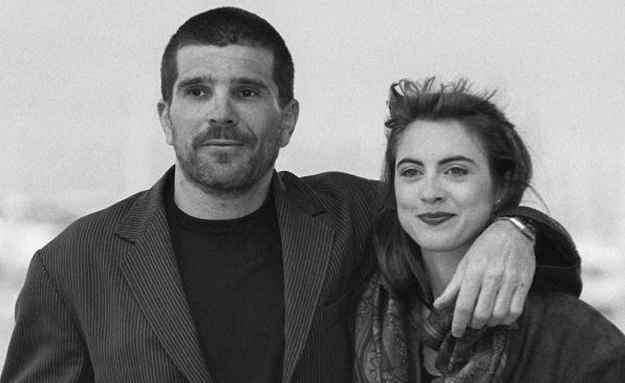

“Here we are,” said David Mamet. He had arrived with his fiancee, the British actress Rebecca Pidgeon. He rattled the doorknob.

“It’s locked,” he said. “The door is locked.” Like the characters in his plays, he uses vocal repetition to set up a certain conversational rhythm.

“Here’s our lunch,” I said. “I signed for it.”

“Great. We have our lunch. At least we have our lunch.” He nibbled at a potato chip.

“I’m here!” said Cara White, rushing down the corridor. She was the publicist for “Homicide.” “You guys beat me.” She rattled the door knob.

“It’s locked,” she said.

“The door is locked,” said Mamet.

“The man who is supposed to have the key is supposed to be here,” Cara White said.

“We could go upstairs to our room,” Rebecca Pidgeon said.

“We could go upstairs,” Mamet said. “We have our sandwiches here. We could take them upstairs with us. We’d better take the elevator, because the room is on the sixth floor.”

Each of us took a plate, and I wedged a bottle of Perrier under my arm and found a hand free for the mustard. We walked into the elevator holding our sandwiches solemnly in front of us. The doors closed and the elevator started to ascend.

“Uh-huh-huh-hum,” said a man with a moustache who was already in the elevator.

“Huh-hum,” I said.

“These are our sandwiches,” said Mamet. “We have our sandwiches here.”

“Huh-huh-hum,” the man said.

“Ah-hum,” I said.

We got out on the sixth floor and walked to Mamet’s room. Rebecca looked inside and said it was still a mess. The maid had not yet come.

“I’ll make the bed,” she said.

“We could sit on the floor,” Mamet said.

“Here is a table,” I said. “We could get chairs and eat in the corridor.”

“Madame,” said Mamet, speaking to the maid in excellent French, “is it possible for you to make the bed? We have our sandwiches.”

“Ah, oui, monsieur,” said the maid, also in excellent French. “Pas de problem. Sand-weech? Appelez le room ser-veece!”

“No, madame. We have our sandwiches. These are our sandwiches. We already have them.”

“Mais oui, monsieur! C’est ca!”

“We could go down to the dining room,” Cara White said doubtfully, looking at her watch. I did not have to guess that Mamet had another interview scheduled in no time.

“We could go to the dining room,” Mamet said.

We walked back to the elevator and took it down to the lobby, and walked through the lobby to the Terrace Room.

“A table for four,” Mamet said.

“Oui, monsieur,” said the maitre d’, looking hopelessly around the room. “The buffet, it is finished almost.”

“These are our sandwiches,” Mamet said. “Could you take the sandwiches? We have come downstairs for lunch.”

“Of course! Le sandwiches!” the maitre d’ said, indicating them with a dismissive hand. A waiter solemnly took the sandwiches from us and disappeared with them. I was left holding the Perrier and the mustard.

“Eef you will follow me,” the maitre d’ said, leading us to a table.

“Le buffet,” he announced, indicating with a bow a long table from which dishes of food were being quickly removed by several waiters.

We sprang to our feet and moved with a certain haste to the table, where we attempted to fill our plates faster than the buffet could be cleared. Moving quickly, I speared a slice of cold salami from a platter as it was being carried past me. We returned to the table and regarded our spoils: Several lettuce leaves, some beets, a slice of salami, and a spoonful of curried herring.

“Perrier?” I asked.