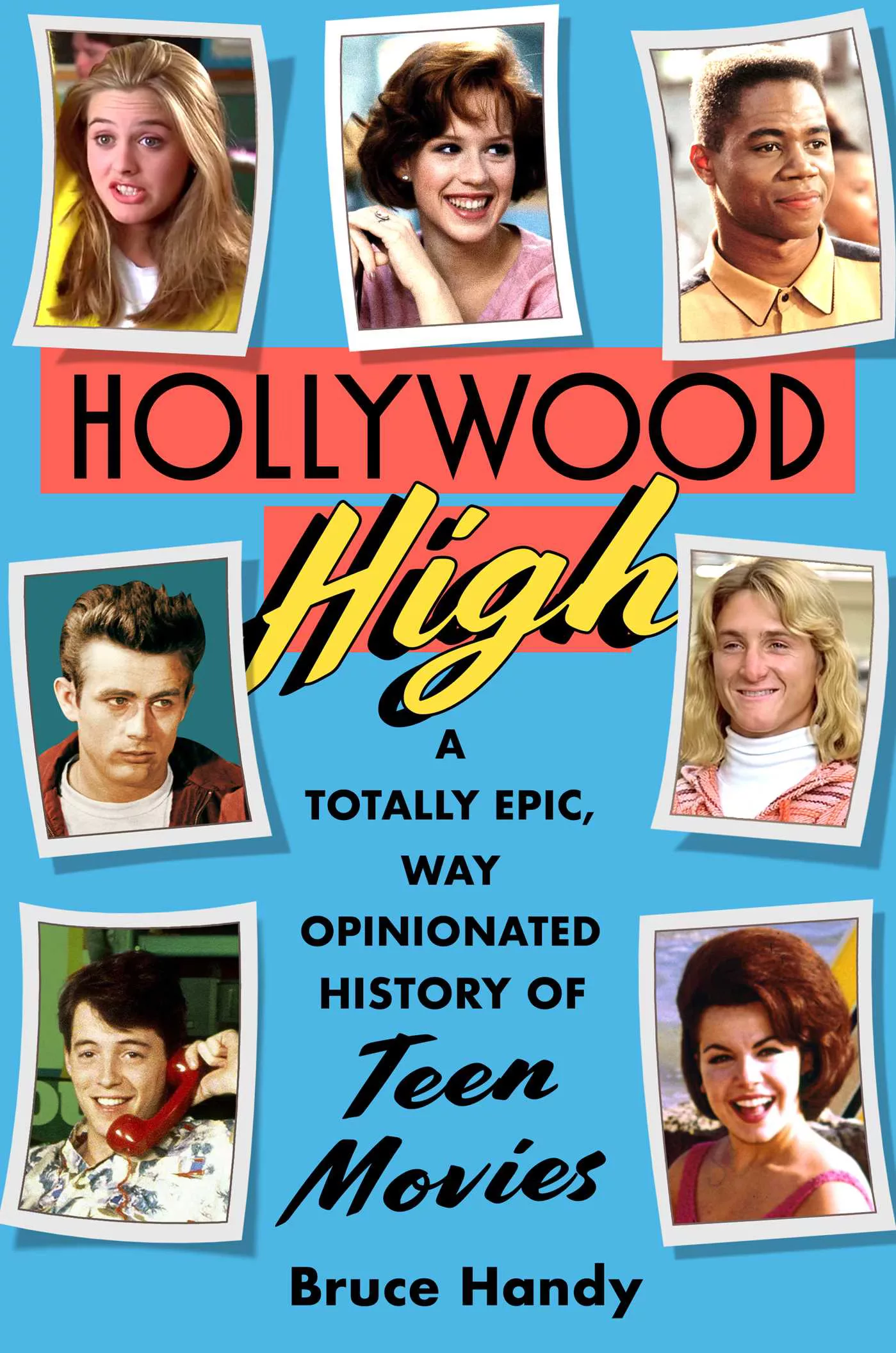

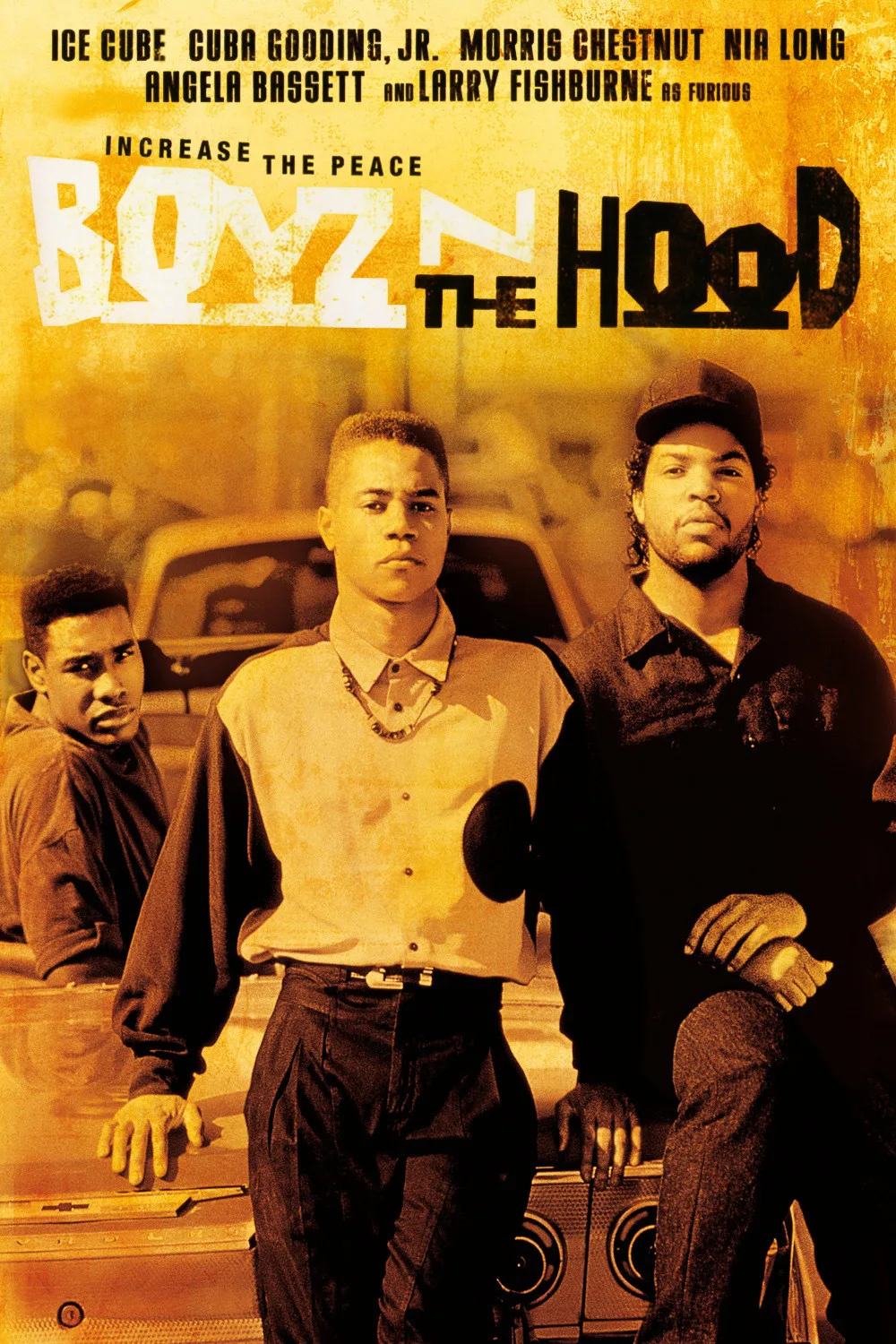

Bruce Handy’s book, Hollywood High: A Totally Epic, Way Opinionated History of Teen Movies, is an absolute delight. It’s filled with fascinating details, first about the “invention” of the idea of the teenager as a separate way of life in the early 20th century and then as a consumer powerhouse and cultural force in the mid-century and beyond and then about the movies about and for teenagers, as a reflection and influence. He begins with Andy Hardy and “Rebel Without a Cause” and then takes us through the beach party movies, “American Graffiti,” “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” John Hughes, “Boyz in the Hood,” “Clueless,” “Mean Girls,” and the dystopian franchise “The Hunger Games” and the vampire romance “Twilight” trilogy. His discussions include behind-the-scenes details of the films’ productions and reception, and his own critical assessment (mostly positive, always sympathetic).

In an interview, Handy sits with RogerEbert.com to discuss his inspirations, the teen film’s ties to the politics of the ’60s and ’70s, and what exactly makes a teen movie.

What inspired you to cover this topic?

I was at Vanity Fair for a lot of years, and it started out as a pitch to do an article. It is an underserved genre in terms of people writing about it interestingly and respectfully. There are great books about the making of some of them, but there’s not one about “Boyz in the Hood” or “American Graffiti,” though there has been great writing about both. I just felt like nobody had really pulled together the whole arc of how these movies evolved and how they reflect what’s going on culturally and in terms of what producers in Hollywood think will sell.

I realized there’s no way I could cram basically 80 years of movies into a 5,000-word Vanity Fair article. So, a book.

I’m not trying to be exhaustive. I left out movies like “Blue Denim,” a 1959 film with Brandon De Wilde and Carol Lynley, about teen pregnancy. And I really don’t touch at all on teen TV, like “90210,” “Dawson’s Creek,” and “Riverdale.”

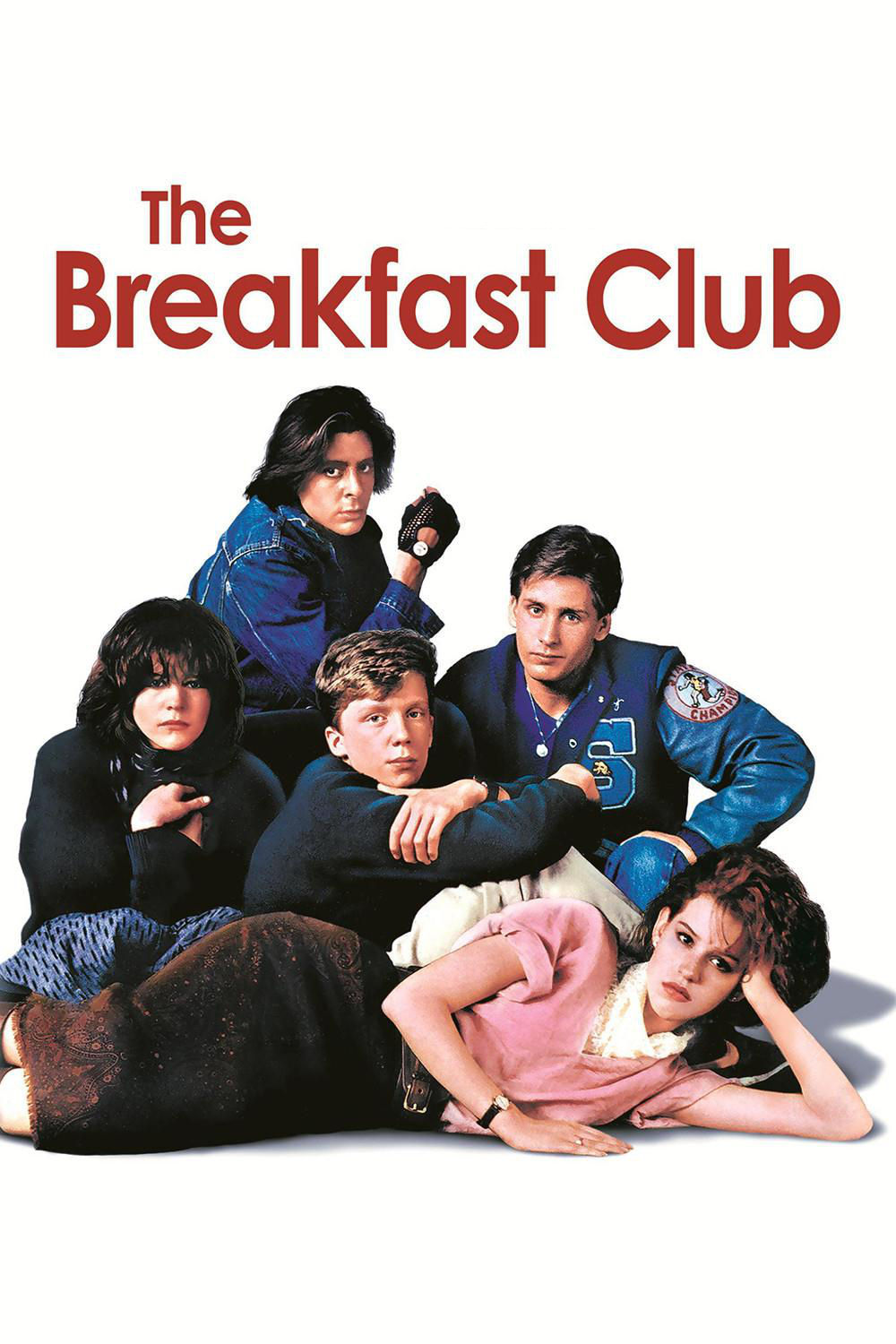

I was fascinated with what I can only describe as the invention of the teenager in the early 20th century. I had no idea that before that, only a small percentage of teenagers finished high school, only six percent in 1900, which is when my public high school began, the one that inspired the name “The Breakfast Club” for John Hughes. Young teens often went into the workplace with adults.

You make a very important point that when that shifted, and most teenagers went to high school for the first time, they were with other teens every day, which significantly influenced the development of teen culture as a separate category.

There’s a real cultural sea change in the first part of the 20th century. It basically leads to the world we know now. Because the teenage world we all grew up in didn’t really exist even a few decades earlier. It was so fun reading the stuff from that time period where people are just trying to wrap their heads around this whole new phenomenon.

In the 1950s, the era of the nuclear bomb and the Red Scare, wasn’t juvenile delinquency one of the five problems adults identified as the most worrisome?

Yes, it was huge. Definitely, obviously, there were juvenile delinquents, and there were kids who committed horrible crimes, but in terms of the notion that this was a cascade, a growing problem, statistically, it just wasn’t true. It was such a paranoid time that these things got so overblown.

You gracefully acknowledged that there’s no way to define what a teen movie is. But do you think it is one about teens? Or for teens?

“Kids,” for instance, I think is about teenagers, but I’m not sure that it is really for teens, though. Something like “Splendor in the Grass” is also about teenagers, but not really for them. There are obviously a lot of movies that are for teens that I don’t consider as teen movies, like Elvis movies, to the Taylor Swift concert movie. They’re aimed at a young audience. “I Know What You Did Last Summer” is about teens, but not really about what it’s like to be a teenager.

So I’d say teen movies are movies that deal with the peculiarities of being a teenager, the social issues, the issues of growing up, sometimes the economic issues. They’re movies about the state of being a teenager.

It’s funny; I think of the first real modern teen movies as the 1937-1946 Andy Hardy movies, with Mickey Rooney as all-American teenager Andy Hardy. But those are interesting because they start as family movies, and the main character in those first movies is Andy’s father, Judge Hardy, played in the first film by Lionel Barrymore and after that by Lewis Stone. Through this kind of alchemy of what was going on in the culture at the time, and also Mickey Rooney’s charisma as a movie star, he ends up taking over the series, like the way Fonzie ends up taking over “Happy Days” or Urkel takes over “Family Matters.”

So the first teen movie was originally built around a father, and the father still plays a very important role in those movies. There’s always a kind of ritual where Andy has to get advice from his wise father.

Yes, you have a funny story in the book about President Roosevelt meeting Mickey Rooney and pretending he was going to give him a fatherly talk.

The Andy Hardy movies set the template for looking up to fathers, but then you start getting to the delinquent films pretty quickly. It’s funny that the movie title is “Rebel Without a Cause”; the first 20 minutes of the film show you that these kids all have problems with their parents. A caretaker is raising the Sal Mineo character, and his parents are completely absent. James Dean’s father, Jim Backus, is ineffectual and effeminate in 50s terms, cowed by his wife. He even wears an apron. Dean, at one point, says ‘if only his father would hit his mother.’ Natalie Wood’s character has a father who cannot deal with her sexuality. She puts on lipstick, and he calls her a tramp and essentially throws her out of the house.

So we go from this movie with this great patriarch setting his son on the right track to a film about kids whose parents completely fail them. That is the beginning of when teenagers start asserting themselves culturally. Part of the reason for its success was that it spoke so directly to teenagers. They didn’t necessarily have to listen to their parents, and their parents might even be failing them, and obviously, that resonated with a lot of kids.

The parents in “Rebel Without a Cause” are deeply flawed, but they’re still real characters. Eight years later, you start getting into the beach party movies where there are no parents and the adults are just ridiculous stooges and comic relief.

And then you get to movies as different as “American Graffiti” and “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” both movies about teenagers made for the first time by people who themselves grew up in modern teenager culture. Parents are just completely non-existent. There are some funny teacher characters in “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.” But essentially, both those movies take place completely in teen world bubbles, which is how teenagers would like to think of themselves. When I was a teenager, the last thing I wanted to think about was my parents. Filmmakers are cannily or intuitively crafting their movies in this way and either making fun of or totally marginalizing adult characters.

In “The Breakfast Club,” every character has a soliloquy about how horrible their parents are in one way or another. It’s not really until “Boyz in the Hood,” where you have Laurence Fishburne’s character for the first time in about 40 years, that there is an actual strong father figure. He has some conflict with his father, but he essentially respects his father, and the film respects the character.

Pretty soon, you’re back to films like “Mean Girls,” in which the Amy Poehler character is a quintessential 21st-century ridiculous parent figure who calls herself the “cool mom,” bending over backwards to flatter or suck up to her own daughter.

Some of the movies you write about hold up better than others.

Yes, I put “Sixteen Candles” on with my kids when they were probably eight and ten. There’s racism, there’s date rape. I liked that movie when it came out. I always had a problem with Long Duk Dong. But I don’t remember being sad or outraged by some of the other stuff.

You mention two films as favorites and both are by the same woman director, Amy Heckerling. “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” and “Clueless.”

In some ways, they’re very different. “Clueless” is obviously much broader and more of a fantasy. But I think it’s still very grounded. “Fast Times” is certainly very grounded. They both have good combinations of being honest but sweet, sweet, but not sentimental, not cloying.

Amy Heckerling has a great eye for casting. Many great performers got their start in her films: Sean Penn, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Phoebe Cates, Alicia Silverstone, Paul Rudd, and Forest Whitaker.

Those movies are so of their time, right? I mean, especially “Fast Times” is so kind of rooted in that kind of early ’80s, late ’70s world, but it doesn’t feel like they are dated.

It’s interesting that lately, for most of this century, the really good teen movies have had women writers or directors: Tina Fey, Stephanie Meyer, and “Twilight;” Suzanne Collins, and “Hunger Games;” Olivia Wilde, with “Booksmart; “Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret” from Kelly Fremon Craig and Judy Blume; and “Lady Bird” from Greta Gerwig.

You very wisely give a good deal of attention to John Hughes. How did he change the world of teen movies for the better? And did he change them for the worse as well?

Certainly there were earlier filmmakers who took teenagers seriously, but somehow, he was able to get deeper—into their skins. There’s something about those movies that feels like they really speak more directly to teenagers than I think some of those other films did, where it always still feels like there’s an adult perspective scrim kind of in front of the characters.

All the stuff you read about him says he very much identified as a teenager. He actually liked to hang out with them. Whatever the flaws are, the John Hughes teen movies are the work of an artist who’s trying to say something to the best of his ability. He had that ability to connect.

I’m going to give you a couple of categories and a character from teen movies and give me what you think is the best. The first is romance.

“Say Anything.”

Death.

I guess “River’s Edge” is the first one that comes to mind. And “Boyz in the Hood.”

Teachers.

Mr. Hand, played by Ray Walston in “Fast Times.” They had originally offered that role to Fred Gwynne, who turned it down. Ray Walston is so perfect. He’s kind of comic relief, but he’s real. Even though he’s ridiculous, he obviously cares about the students, and he actually gets through to Spicoli at the end of the movie. So there’s respect.

Is there one movie that you think is underappreciated that you want everybody to be sure to see?

I would say “Gidget.” I think Gidget is a really interesting, really interesting movie. And I think Sandra Dee is really great in it. It’s obviously dated in a lot of ways, but it grants that she would be interested in exploring her sexuality and it’s surprisingly watchable.