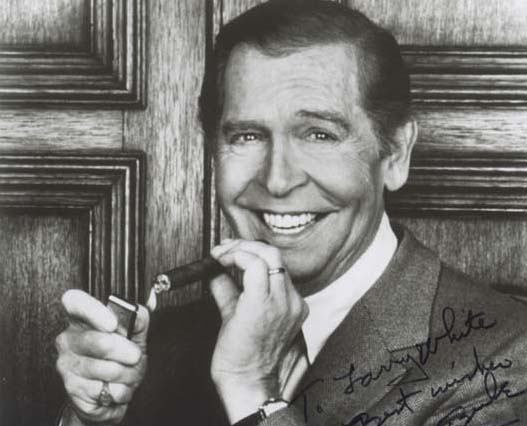

TORONTO – “You wanna know what the difference is between a comic and a comedian?” Milton Berle asked. Yeah, I wanna know.

“A comic is a guy who says funny things.” Berle drew on his cigar. “A comedian is a guy who says things funny.”

Which are you?

“Depends on how I got up in the morning. There is only one comic situation, anyway. It comes in three steps. One, get the comic up in a tree. Two, throw rocks at him. Three, get him down out of the tree. Part 3 is the happy ending. Without the happy ending, it’s not comedy. Aristotle.”

Berle stretched out on a sofa, He was wearing a bathrobe and a two-day beard. He was on the set of “Off Your Rocker,” set in an old-folks home in Toronto. Berle, Lou Jacobi and Red Buttons were playing the three old folks.

“Old? Have I got a story for you,” says Berle. “They gave me an honorary Emmy for my three decades in television. I came on TV in 1949, so this is 30 years later. Have I got news for them. I was on TV for 50 years. In 1929, there was this outfit known as the United States Television Co., across from the Chez Paree in Chicago. They were experimenting. I did a show. It was in a room the size of a broom closet, filled with lights, and my lips came out looking as black as Theda Bara’s. Twenty years later, I figure the medium is finally ready for me,”

What was it like doing live television?

“What you saw was what you got.”

Since it was live, you couldn’t do it again?

“Since it was live, if you couldn’t do it the first time, that was the show. If the backdrop fell over, you held it up with your hand and said, They’re not making these things the way they used to.”

So if you told a joke and it bombed, what did you do then?

“If it bombed? They had audiences in those days, to them, laughter was a foreign language. I had a whole list of things to say when a joke bombed.”

Like what.

“Like what, he says. Like OK folks, here’s another one you may not care for. There must be people out there, I hear breathing. Tap your canes when you want to laugh. Working this audience is like walking a gangplank without a ship. Did you come in here for entertainment or revenge? I feel like the captain of the Titanic. May I see your library cards? I’ve never been funnier, folks, and believe me I sincerely regret it.”

Live television, must have been a constant challenge.

“I sold a lot of sets. After I was on, my neighbor sold his set, my wife sold her set . . .”

I mean, did you work with a script, or . . .

“No cue cards, no TelePrompTers, just memory. My experience in vaudeville was a great boon to me. I got stuck; I could remember some old routine from the State Lake. I remember I played Chicago once in legit. ‘Adam and Eden,’ I think it was called. People went out whistling the scenery.

“We were only sort of live, anyway. We were really live, but only to those places on the coaxial cable. We were live in New York, and we went out live to Chicago, but for the West Coast, we were on kinescopes and they sent us out by train and we were on a week later.

I remember how I got the nickname Uncle Miltie. My floor director in those days was Arthur Penn, who went on to become the famous movie director. In those days, he would squat under the camera and give me signals so I knew how much time I had left. One day we had a new script girl. She timed the script, and made the mistake of allowing too much time for the laughs. With our scripts, allowing any time for the laughs was taking a risk.

“So I think the show is over and I’m standing there saying goodbye, and I look down at Penn, and he’s holding up eight fingers. Eight fingers. That means I’ve got eight minutes to fill. And nothing to say. I started ad-libbing, doing old jokes from vaudeville. Finally I ran out of jokes. I started talking to the kids: Time to go to bed, kiddies! Uncle Miltie says goodnight! The next day, they were calling me Uncle Miltie, and it stuck.”

Tell me more about this movie.

“We’re in an old-folks home, and the old folk who runs it is about to lose his position, and some cost-efficient computer experts are going to revolutionize things, and we go on a strike. You want to know anymore, ask Lou Jacobi. I think he’s actually read the script.”

Down the hallway, Lou Jacobi was also in a bathrobe, two-day beard, the works:

“Whatever Berle says, he’s right, I got started in this business selling shoes, what do I know? Five bucks a day in Paterson, NJ, selling shoes. Ten thousand shoes. A guy walks in, offers me a job as a singing waiter, $6 a week and I’m a bellhop during day. As a waiter, I’m a little inexperienced. I don’t know muscatel from beer. As a singer, I’m OK.

“So I see show business is for me. So I have some success in and around Toronto, working stag parties. My first booking was in front of 200 drunks. ‘Gentlemen!’ I start out. ‘Jacobi stinks!’ they shout. ‘Give me my $35 and send me home!’ I reply. I was a hit. I found out a technique for making dirty jokes palatable, by going into all the characters with different accents and so forth. That’s how I became a character actor, telling dirty jokes. And mother-in-law jokes, they didn’t even have to be dirty.”

TELL ME one.

“Guy’s 50 years old, he’s still a bachelor. He can’t find a girl his mother will approve of. He brings home one girl, she’s too fat. Brings home another girl, she’s too skinny. One talks too much, the other’s a wallflower. Finally, the guy brings home a girl who he knows his mother will approve of, because this girl, she’s exactly like his mother.”

What happened?

“His father hated her.”

You’re a character actor who started out as a comedian?

“Yeah. You know the difference, between a comic and a comedian?”

AH … NO. What is it?

“A comic says funny things. A comedian says things funny.”

That’s funny. I’ve heard that somewhere before.

“Of course you have. Ed Wynn said it.”

Milton Berle just told it to me!

“You know what they call him, don’t you?”

No, what?

“The Thief of Bad Gags. That’s a joke.”

I wish I had said that.

“Don’t worry. You will.”