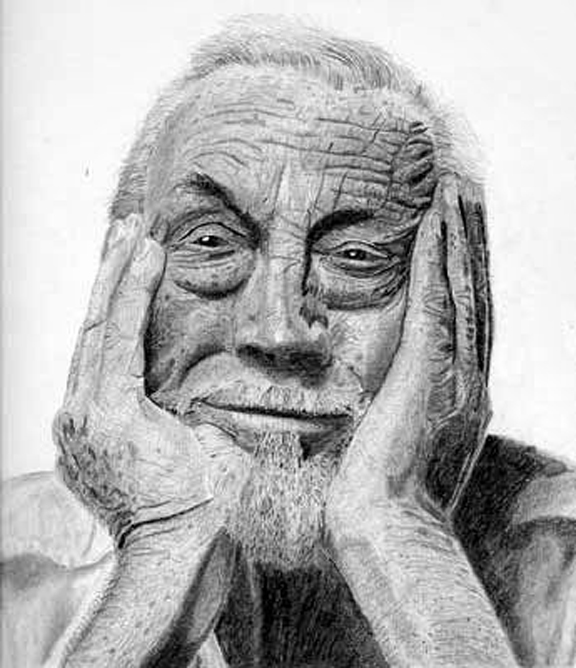

Cannes, France – An old lion named John Huston came to the Cannes Film Festival last week, and growled at his critics and smiled at his friends and brought along a new movie so sleek and angry it’s hard to believe it was made by a man who is 77. The name of the movie is “Under the Volcano,” and it’s based on the heartrending novel by Malcolm Lowry about the last 24 hours in the life of an alcoholic British vice-consul who drinks to love and loss and dreams of greatness before his murdered body is eaten by wild dogs.

Under the Volcano is on most lists of greatest novels of the century, along with Ulysses, Remembrance of Things Past and The Sound and the Fury. But it had never before been filmed, perhaps because its style seems almost unfilmable.

The book is an extended stream-of-consciousness inside the confused and hallucinating mind of the hero, a man named Geoffrey Firman who has been drinking so much for so long that his thoughts are like a kaleidoscope.

The novel is set in Cuernavaca, Mexico, not far from where John Huston has maintained a home for 30 years. And it has been almost that long, Huston said, since he started trying to lick the problems of filming the novel. “I’ve read it countless times,” he said. “I’ve discussed it, sometimes one page at a time, with people who know it even better than I do. There have been at least 60 screenplays attempting to solve its problems, and I’ve read at least 25 of them. They all made the mistake of trying to show all the symbols and allusions and literary flights of fancy. The problem was to reduce the novel to its fundamentals.”

That he has done, and Huston’s best decision, in trying to find a clear line through from the beginning to the end of Geoffrey Firman’s last day on Earth, was to cast Albert Finney in the crucial role of the haunted former consul. Finney gives, quite simply, the best drunk performance I’ve ever seen in a film.

He does not do it by relying on any sort of existing tradition – the stage drunk, the flamboyant drunk, the pathetic drunk. Instead, he plays a man who, with great difficulty and no small measure of dignity, is trying to force his words and thoughts through decades of alcoholic fog to the world that must surely be somewhere outside. There are scenes where the words arrive with such pain that we almost expect them to come dripping blood and tequila.

Huston and his screenwriter, Guy Hallo, have made the wise decision to leave all of Firman’s hallucinations, fantasies and nightmares inside his head. The movie contains none of those routine drunken-fantasy scenes in which apparitions swim in and out of focus. Instead, we see only externals, places and faces, and it is Finney’s job to suggest the demons inside his head.

Those ground rules are established early, in a scene where the character is sitting in a bar, early in the morning, drinking to keep away the shakes, boring the proprietor with an incomprehensible story of events long ago. He has been praying for the return of his wife (Jacqueline Bisset), and now, unexpectedly, she steps into the doorway, He turns, sees her, turns away and continues his monologue. Intrigued by the reality of his apparent vision, he turns and looks again. It takes him four turns before he can find the courage to say anything aloud to what he clearly believes is a hallucination.

The movie was cheered here, where it is Huston’s third official selection over the years (after “Fat City” and “Wise Blood”), but the first to be in competition. And after the early morning screening, Huston’s press conference was the first stage in a long, grueling day for the old man – the oldest film director in the world who is still active with major feature production. Some of his movies, like “The Maltese Falcon,” “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” “The African Queen” and “Moby Dick,” seem so firmly enshrined as legends that it was a little startling to see him here in the flesh, talking about the new one.

He talked a lot about “purifying” the novel, removing or combining such characters as Bisset’s two lovers, reducing the events in the interpretation of Firman’s drinking: “He is a hero, not a victim. A giant. His drunkenness represents not self-destructiveness but outrage. It is his defense against the assaults of the world.”

Huston himself has been known as a colorful drinker over the years, particularly when he maintained a castle in Ireland and led the local hunt. He was asked how his own experience with drinking was reflected in the movie.

“When I drank,” he said, “it wasn’t self-destructive and not in the least bit heroic. I enjoyed drinking, and I still do, but I was not an alcoholic and didn’t have to apply my own experience to it. What I did contribute to the film, from my years of living in Mexico, was whatever I understand about the way that belief in the supernatural, in miracles, affects everyday life there.”

I asked a question that I suspect was on the minds of more than one person who watched Finney’s extraordinary performance: “With all respect to Finney, who gave a great performance… I had the impression that in some scenes he was actually drunk.”

Huston disagreed, but in a way that almost seemed a confirmation: “He didn’t drink while he worked. He waited until after we were done. But his understanding of drunkenness is a very profound one, bolstered by his own extensive experience.”

Huston said he saved himself a great deal of trouble on the film by casting it correctly: “Finney and I had only one serious discussion about our interpretations of the character. He understood the consul as thoroughly as any actor has ever understood any character. He knew exactly what he was doing, and we seldom had to shoot any of his scenes more than once or twice.”

After the press conference was over, Huston still had a grueling day ahead of him. There were business meetings, interviews and then the black-tie official premiere in the evening, which drew the biggest mobs of fans and photographers of any film this year. Finney wasn’t here, but the combination of the legendary Huston and the beautiful Bisset (who is half French) was an irresistible draw.

After the evening screening, 20th Century-Fox hosted a black-tie dinner for at least a thousand people at the town’s Palm Beach Casino. And it was there that I glimpsed a small moment of John Huston’s long life that was quietly revealing.

Huston and Bisset were mobbed by reporters and cameramen. Huston, tired now and suffering from jet lag, agreed that yes, he was happy his film had been well-received, and yes, he was pleased by the ovations. Then he and Bisset were whisked into a room away from the crowds, and I received a short audience.

He began in the familiar Huston persona, affable but unrevealing: It was grand to be here at Cannes, he loved the excitement, he loved the crowds, he was very gratified that people had liked his film. It was not, he knew, a “commercial” film with a lot of special effects and action sequences, but he thought it told its story well and truly.

I asked if his previous films here had been in the competition.

“No, they were out of competition.”

But this one is in?

“Yes.”

Why did you enter the competition this time?

“Because I want to win. Oh, yes, most definitely.”