They say he was loud once, and drank too much. But this night James T. Farrell spoke softly, almost to himself, and he said he was off the sauce for the rest of his life.

“I have a lot of work to do,” he said. “I write 20 hours at a stretch; I hate sleep and I fight it. I’ve slept seven hours in the last three days. If it kills me, that doesn’t matter. I’ve already gained more time than I’ll lose.”

He was back in Chicago to visit the South Side for a television show. This was the week before the Democratic convention, and the idea was to take Farrell back to the scene of his Studs Lonigan trilogy and some of his other books. It had changed, but that was the idea: Farrell would look at it and say it had changed.

“Sure as hell some damn fool will ask me how the ghetto has changed since I wrote about it,” Farrell said. “They say I never got out of the ghetto. But Studs didn’t live in a ghetto. They don’t know that, though; they’ve never read the book, or any other book I’ve written. My past is considered better than my future. I’ve had a 15-year struggle to keep alive, to keep writing.”

At 64, Farrell has published 42 books, but he is still known largely because of Studs Lonigan. He writes his novels in groups, beginning with a central character, showing him as part of a very large canvas of society. A minor character in one book will reappear later as the subject of another.

William Faulkner also wrote this way, creating Yoknapatawpha County and peopling it with four generations of residents. To keep his characters straight, Faulkner made card files and drew historical maps, pinning them to the walls of his workroom.

Farrell has created a universe as large, but he keeps no notes. “I keep it all in here,” he said, tapping his head. “If you check my books, you’ll find less than 1 percent error. I don’t need any maps. I don’t need to look anything up.”

First there was the Lonigan trilogy, about a middle-class Irish kid on the South Side, who grew, dreamed, lost hope and died. “Studs wasn’t such a great failure,” Farrell said. “He drank and died. If his father’s business hadn’t failed, it would have been all right with him. But he had no imagination.”

Farrell’s novels have charted a gradual way out of the spiritual poverty, the famine of imagination that killed Studs. His next series of novels was about Danny O’Neill, who grew more, got out of the trap of the neighborhood. Then he wrote the Bernard Carr trilogy, bringing the development farther: Bernard went to New York, became a writer, found a way to use his experience.

Farrell left Chicago as well. For the last three decades, he has worked in New York, in recent years living in one room of a Greenwich Village hotel. Those who have been there say the room is filled with manuscripts, with millions of unpublished words. Farrell speaks of a final grand project, The Universe of Time, a cycle of perhaps 20 novels.

“They say I made a lot of money in Chicago and then deserted it like a traitor,” Farrell said. “I didn’t choose New York, I got stuck there. I’ve never been a rich writer. I live in a room and I have 4,000 books and no other property. I gave away my typewriter, my television set, I don’t have time for that. I write in longhand, one draft, and then a revise.”

One of Farrell’s visitors wrote a few years ago that he writes in soft lead in notebooks, pressing down so hard on the pencil that his fingers bleed after a day of writing. It is the sort of detail you hesitate to check: How would you ask Farrell if it were true? One is embarrassed in the face of such dedication.

“The reason I have 42 published books instead of 50, he said, “is that I couldn’t get the others published. It’s very simple. And four of my novels were burned in a fire. My books sell, but the publishers let them go out of print. A World I Never Made sold 40,000 copies; that’s supposed to be a best-seller. But it’s out of print.

“And then people consider me a great failure, because I’m not a millionaire. I never tried to be a millionaire. You can’t do it and be a writer.” Studs Lonigan remains his best-selling book, of course, and for many years, it has been in the Modern Library reprint series. This year, he said, he expects to make $125, maybe $150, from Studs Lonigan.

In the 1930s, when the Studs Lonigan novels were published, Farrell was hailed as the master of American realism. He still writes the same way, with the same vision: His latest novel, A Brand New Life, is set in Chicago and tells of the desperate lives of people who so lack imagination that they believe they are happy. His sentences follow one another like bricks in a well made row. His prose is simple and direct, powerful and blunt. He has no use for the facile style of authors like John Updike.

“See,” he said, “I like to write. I’ve never had writer’s block so much as a day in my life. If I block for an hour, that’s a long time. I know what I want to write; my problem is to find time to get it all down.”

What about J.D. Salinger? he was asked. What about Salinger, who wrote “The Catcher in the Rye” and whose production has grown less with every year, until finally it seems every word must be torn free.

“Well, maybe Salinger didn’t have anything more to say,” Farrell said. “There’s no point in writing if you don’t. There are too many writers. One thing pleased me: Time said I was the worst writer in America. I take that as a great distinction.” The problem with writing in America, he said, is that literature has been overrun with college professors, literary critics, creative writing classes and damned fools.

“They asked me to teach a creative writing class once,” he said. “I said it was a fraud, nobody could be taught to write, but I would do it under two conditions. First, that I could do all the writing; second, that I could seduce all the girls.”

What about the boys?

“They could imitate their teacher.”

He grinned. There’s an echo of an Irish accent in his voice, very distant, but his face is Irish and so is his sense of humor.

“The Irish are a dour and verbal people,” he said, “but they make fine revolutionaries. I remember old Jim Larkin, who organized the first citizens’ army and fought for the IRA. When the British arrested him, he stood in the dock and said: ‘It is my divine mission to preach subversion and discontent to the working class.’ He was a communist, but he was an Irishman.

“I went to Dublin once and Jim Larkin took me around, introducing me to all of his friends. He told them: ‘I want you to meet my friend Farrell, who has written a psychological novel that you dare not read or you’ll lose your immortal soul’.”

Farrell chuckled softly. “Jim Larkin knew literature. These professors…one of them came to me and said I might decline. Said I was too much interested in Stendahl; I might lose my working-class instincts. What a damn fool. I refuse to be confused by words. I would rather let a woman do it.”

Farrell had his first bitter experience with literary critics in the 1930s. The Lonigan trilogy was praised by the communist critics as a working-class statement, but by the late 1930s Farrell was no longer in favor. He had strayed too far from left-wing orthodoxy, following his character’s where their lives seemed naturally to lead.

“The FBI has left me alone, and the Air Force,” he said. “Everybody else has had a go at me. Congress denounced me, and the Church, and Ireland, and the Third Reich, and South Africa, and Racine, Wisconsin. I have been on every side of everybody simply by moving in a straight line.”

He supported Hubert Humphrey for the Democratic nomination.

“I know Eugene McCarthy well,” he said, “but he’s playing with frustration. He hasn’t thought the issues through. He’s appealing to people for the wrong reasons. They say he has great support in the suburbs. That’s because the suburbs are filled with adults who want to swing like their children.”

You could look at his face and see that James T. Farrell would never “swing,” and never want to.

But he said his real candidate this time around, the choice of his heart, was Bobby Kennedy. “He had more promise than John Kennedy,” said Farrell. “He was a shy man, he loved life. When the first Kennedy was assassinated, I wrote a poem. It was inserted in the Congressional Record. It wasn’t very good, though…

“And I wrote one about Stevenson, a shorter one:

The lonely world is lonelier,

Because the lonely man is gone.

He said he had just finished a book, “Native’s Return,” that is set in the Chicago of the 1950s and ends with Stevenson’s 1956 Presidential nomination. Among those political figures he respects, he said, it would be hard to find two more worthy than Stevenson and Paul H. Douglas. A Brand New Life is dedicated to Douglas and his wife, Emily.

“They both had a wider vision than you see today,” he said. “They believe all those who are victims of injustice must unite. Now all this Black Power stuff—that’s black fascism, if you ask me. No, say it’s adventuristic. Black and white together against injustice, that’s what we need.”

Farrell said he is bitter sometimes that his books have to struggle for their way, while he is called upon to support younger writers. “A writer worth a damn doesn’t care what other writers think of his books,” he said. “I write a book and it’s finished. I don’t go running around town asking other writers to read my manuscript. “But a lot of younger writers, particularly the bad ones, think it’s my duty to read their books. The main point most of these first novels make is that the author is 21. And my eyes are bad. I have more important reading to do.”

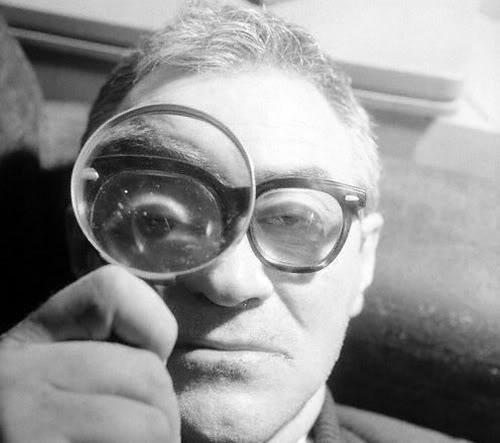

All this conversation took place in a small restaurant near Old Town. After dinner, Farrell walked through the neighborhood unrecognized. His face is not familiar; he goes on television only rarely.

Eventually, his steps led near Sandburg Village, that enormous apartment complex with each building named after a famous American writer. He was asked if one were named after him.

“Not that I know of,” he said.

They will name one after you some day, he was told.

“God, I hope it’s after I’m dead,” he said.

He walked on. “It will all come after I’m dead,” he said at last. “The Nobel Prize…sometimes I think I’ll have to die before anything happens.”

He said he was ready when that day came, and once again there was the Irish smile and the dour Irish wit. “I’ve written my own obituary,” he said:

James T. (for Thomas) Farrell, Who might have been this,

Or who might have been that,

But who might have been

Neither this nor that,

And who wrote too much, who

Fought too much, and who

Kissed too much,

(He needed no enemies)…

That man, J.T.F., died last night

Of a depreciation of time,

And willed his dust to the public domain.

By then it was time to go back to the Blackstone Hotel, where he was staying.

As he was driven toward the Loop, he kept a lookout for a drugstore that might be open late. He wanted to buy more notebooks; he planned to write all night.