Dalton Trumbo‘s “Johnny Got His Gun” seemed for years to be one of those novels that could never be made into a movie. It took place entirely within the mind of a soldier who was so grievously wounded in World War I that he had only the most tenuous contact with the world. He had no arms, no legs, no sight or hearing, no way to speak.

The only reason for keeping him alive, the Army decided, was to learn from him how to treat others. It was assumed that he was a human vegetable with no conscious mind; but in fact there was a mind inside, intact, feeling the vibrations as doctors and nurses approached his bed, and trying desperately to communicate with them.

Trumbo’s novel, published in 1939, was made from the soldier’s stream-of-consciousness, which drifts back and forth between the present and the past, and occasionally lingers in fantasies (as when he discusses his fate with Jesus Christ).

This was material for a novel or even a radio play (Arch Oboler produced it for radio in 1940, with James Cagney as the soldier). But how could it be made visual?

“There were many times during the first 20 years of the novel’s existence when I received offers for it,” Trumbo recalls, “but I’d never let go of it, not even when I could have used the money. It’s obviously the best thing I’ve ever done maybe the one good thing I’ve done – and I told them, ‘I can’t see any way to make it into a film, and I’m a fair pro at turning books into movies. So if I can’t, I don’t see how you can.'”

But an offer came in 1964 that he couldn’t resist. It was from a producer representing Luis Bunuel, the great Spanish director. “They wanted to know if I’d do a screenplay for Bunuel,” Trumbo said. “Hell, I said I’d do a screenplay, and be his secretary, and carry his briefcase and do his laundry. I went down to

Mexico and spent some time with Bunuel, of which I best remember the four-hour lunches which averaged out to about a bottle of wine an hour. And then I came back to California and went to work, and by the time I had the screenplay completed, the producer was out of money and Bunuel was back in Spain, broke.

“I’ve always been interested in how Bunuel would have made it. I think he would have savagely attacked democracy. I imagine his approach would have been more shocking than my own. I’ve tended more to center on the young man, the soldier, and let you draw your own conclusions about the system that put him where he was.

“Of course, I’ve gotten a little heat from the Left on that, because I didn’t put in a revolutionary addendum. But that wouldn’t have worked in a movie. In the novel, you have a time lapse. Joe, the soldier, has time to think through to an angry manifesto. But in the movie you see him, and his despair is visual. If he’d immediately hit on some sort of political conclusion, it would have been obscene.”

So what Trumbo did was to stay close to the events, real and imagined, of his novel, and let the ideology emerge by implication. His wounded soldier is little more than a mask and a tent of blankets in the hospital room. Indeed, the character’s very lack of the things we usually use to judge personality – a posture, a facial expression, body language – tends to draw us down into the almost exclusively mental world where he’s imprisoned. And then we see his memories of his childhood, parents, girlfriend and of going off to war.

“I was very concerned that we didn’t spend too much time in the hospital room,” Trumbo said. “When I was writing ‘The Fixer,’ I was concerned that the audience would feel claustrophobic if we stayed too long in that jail cell. So we put in scenes – flashbacks,

fantasies – to get out of the cell. But most of those scenes were removed in the final editing process, and…well, the film didn’t work out commercially. Not enough people went to see it. I wanted to keep ‘Johnny Got His Gun’ opened up.”

At the first (and only) sneak preview, however, Trumbo distributed a long and complicated questionnaire to his audience, and found that the hospital scenes weren’t at all too much. Part of that may be because of a deeply realized performance by Diane Varsi, as the nurse who finally communicates with the soldier.

Many of the flashback scenes are actually inspired by events in Trumbo’s own life. There is a touching scene, for example, on the night before Joe is to go to war. He is kissing his girl in the front room of her home when her father comes home, snaps on a light, and then gruffly says: “Into the bedroom. Both of you.” And they make love for the first time. It will be his only time.

“I knew a girl, when I was young, whose father was this man,” Trumbo said. “He was a Wobbly, spent years in the mines, was bent over from all those years, and was now rather bitter as a railroad bull. He never sent me into the bedroom with his daughter, of course…that was my fantasy.”

Other scenes were also autobiographical. Trumbo, like Joe, was born in Colorado, moved to California when his father became ill, took a “temporary” job in a bakery, and was called home to his father’s deathbed.

“I wondered where we should shoot the deathbed scene,” Trumbo said, “and I finally decided to see if my home was still standing. Well, it was, at 1116 1/2 W. 55th St., in Los Angeles. It was an upper-floor apartment with a rear entrance, over a garage, and we shot the scene there. Jason Robards, playing the father, was lying in the same place where my father had died 44 years before. Well, of course, how elegantly can you play a dead man?”

Trumbo smiled. “But I know it meant something to me. A younger and more talented man would never have thought of shooting the scene there. He would have done something clever. But that’s why I wanted to direct this film. I’m a writer, I’ve never letched to be a director, but dammit, I was there. I know the period and time. I’m older than everybody. I’m even older than Otto Preminger.”

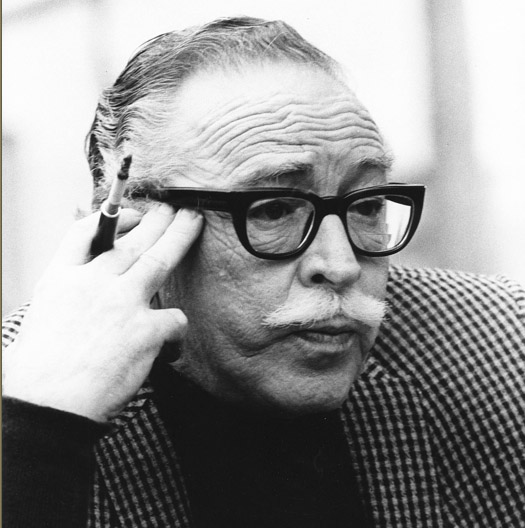

Trumbo smiled again. He is a quietly civilized – one almost says courtly – man, with none of the slickness you sometimes find in Hollywood types who have been very successful for a very long time. But, of course, his career has never permitted very much of that

slickness. He worked for eight years in the bakery (“always thinking it was temporary”) and then struggled in a $75-a-week job in a studio story department before finally winning recognition as one of the best writers at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer during the late 1930s and early 1940s.

But then the blacklist cut him down; he was one of the Hollywood Ten, in 1947, and his next visible credit for a screenplay wasn’t until Preminger’s “Exodus,” in 1960. During the days on what he calls the “black market,” he did screenplays under pseudonyms, and there is the famous story about “Robert Rich,” who won the Academy Award in 1957 for the screenplay of “The Brave One.” “Rich” was Trumbo.

Some of the screenplays were done in a hurry, he remembers. One of his best was “A Man to Remember,” which he wrote in two weeks and Garson Kanin directed in 15 days. “It was a damn good movie,” he says. “It was a busy year. I’d just gotten married and conceived a child…”

Sometimes, he said, the best screenplays have been written in a hurry and the worst have taken forever. But then again, sometimes the worst come quickly and the best take forever.

“There was ‘Exodus,’ for example,” he said. “It was no great masterpiece, but it was at least half of a damn good movie. Preminger had the locations, the starting date, the contracts, everything but a script. He called me on the sixteenth of December. I read the book in two days. It weighed 14 pounds and had 390 characters. I told Otto he had better know what he wanted. He did. I followed him like a dog through the construction. If a scene wasn’t working, I’d jump ahead to something I knew I could write.

“I remember Christmas Eve. Preminger impatiently watching my family unwrapping gifts. I told him I hadn’t bought a damn thing for my wife. ‘Ve vill buy her somethink,’ he says. We went to Pasadena and bought her a bathrobe, A stunning and original gift. But we were finished with the screenplay in six weeks, by God.”

All of this was at the Playboy Club, where Trumbo was eating eggs benedict and drinking a large glass of white wine, and after a while he said he’d never been in a Playboy Club before. “I feel a bit shy,” he said, and laughed. “You know, I was born in Colorado, and I remember the first self-starting car that came to town. And I flew here today on a 747. That’s too damned much for one lifetime.” He finished his wine. “What you’re hearing, of course, is the reactionary voice of age. Pay no attention to it.”