The post-war baby boom in England led to a teen explosion in the ‘60s, and rock ‘n’ roll was the music that provided the soundtrack for the erupting youth quake.

Suddenly, there weren’t only bands such as The Beatles and The Rolling Stones taking advantage of the swarm of adolescents and their bottomless hunger for the next big thing. There also were self-made entrepreneurs eager to offer their services as behind-the-scenes puppet masters of the growing hordes of shaggy-haired young males wielding guitars and bashing drums.

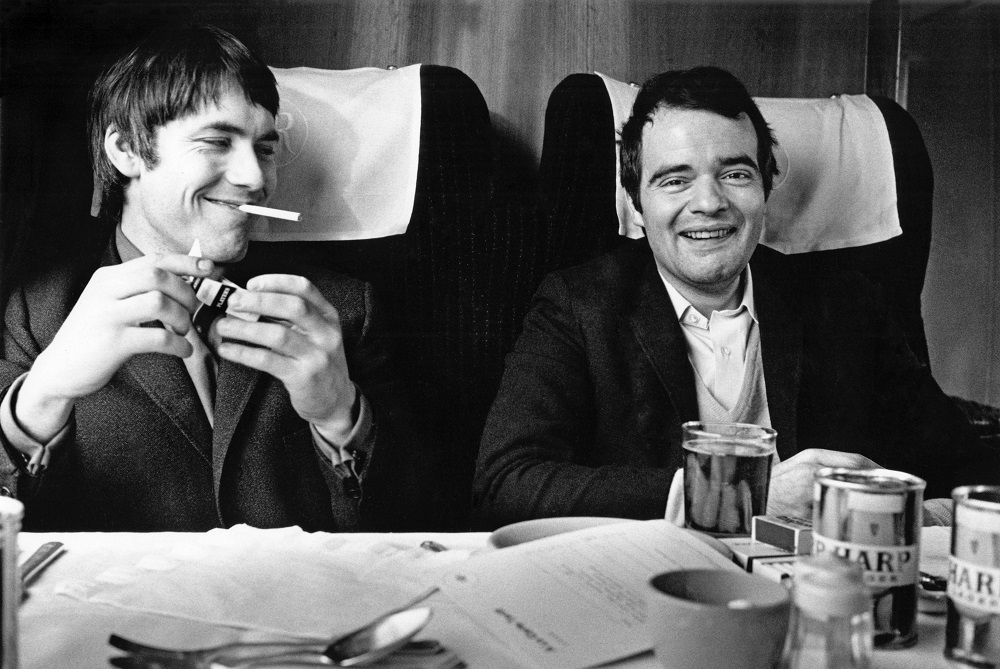

Enter Chris Stamp and Kit Lambert. The girl-crazy working-class son of a tugboat captain and the gay bon vivant Oxford-grad son of a respected classical composer were the very definition of a “chalk and cheese” partnership. But their shared interest in filmmaking, especially the French New Wave style of cinema verite, provided a common bond as they both worked as assistants at Shepperton Studios in the early ‘60s. They were itching to make a movie together and decided to co-opt a band as their subject matter.

That is how they stumbled upon a quartet of scruffy lads who back then called themselves The High Numbers but who would eventually be re-christened as The Who: Gangly guitarist and art-student dropout Pete Townshend, scrappy lead singer Roger Daltrey, moody bassist John Entwistle and crazy-as-a-loon drummer Keith Moon.

As told in the rollicking documentary “Lambert & Stamp,” a breakout hit at this year’s Sundance Festival, the pair never did finish that movie. Instead, cinematographer-director James D. Cooper is the beneficiary of unused footage that captures The Who and their fans (known as Mods) in their earliest days.

Meanwhile, the savvy managers focused on shaping The Who’s image, helped them produce such early hits as “My Generation” and “Magic Bus”, and guided their ascent into the realm of rock gods with the arrival of the groundbreaking rock opera “Tommy” in 1969.

Although there are 44 Who songs that rumble and roar throughout Cooper’s doc, “Lambert & Stamp” is more interested in the unique relationship of these two unusual gentlemen, who readily admit they learned their managerial and marketing skills on the job (as a grinning Stamp says in the film, “We never said we knew how to do it”), and is less about the concert performances.

As is often the case, great success often leads to a falling-out, somewhat exacerbated by substance abuse issues that plagued all the participants save for Daltrey. Soon after Moon died from an overdose in 1978, the surviving members of the band and the managers cut their professional ties for good. Lambert died in 1981 from a cerebral hemorrhage after a fall. Stamp, who provides invaluable onscreen commentary along with actor brother Terence, died of cancer in 2012. Meanwhile, Entwistle succumbed to a cocaine-induced heart attack in 2002.

Despite lingering rancor, Townshend and Daltrey openly profess their admiration and gratitude for their managers in the film. Says the guitarist, who learned about composition and musicianship under the tutelage of onetime roommate Lambert, “I fell in love literally with both of them immediately and they completely and utterly and totally changed my life.”

Cooper, a well-known fashion photographer and cinematographer based both in Los Angeles and in New York who has worked with such well-known documentarians as the Maysles brothers, Bruce Weber and the team of Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, discusses his 10-year journey that resulted in “Lambert & Stamp.”

Just to let you know, I am a longtime Who fan. They were the second concert I ever attended, following The Monkees. I saw them in North Tonawanda, N.Y., at a theater-in-the-round concert tent called Melody Fair during the summer of 1968 on their first American tour. They had just released “Magic Bus.” I remember that Keith’s parade of broken drumsticks were scattered all around the stage. The town had to pass a noise ordinance afterwards when the neighbors raised a ruckus about their ear-splitting sound levels. Did you ever get a chance to see them live?

I did. It was amazing. I came to The Who’s music in the ‘70s. It was very, very important music. Strange and rich and very meaningful and important. And even if you didn’t like the music, you couldn’t not like The Who. There was an intensity about them.

I saw them twice more, including the following year when they performed “Tommy.” But I lost much of my enthusiasm for the band once Keith Moon died.

Chris Stamp lost his enthusiasm as well. He says as much in the movie.

Shooting so much of the doc in black and white was a smart move. It blends with the archival footage and makes it feel like a British film from that time period. There’s something rough and raw about the editing as well, a bit chaotic but with a creative electricity in the air. It feels very much like The Who and the British Invasion era.

The black and white was part thought, part intuition. You let the intellect and the intuitive slug it out. It does feel like The Who. It was a conscious part of the process, the unfolding reality and how you put it together. We don’t rely on a historical chronology. Instead, we use black and white and color to bring the viewer in viscerally.

One of the things that the documentary reminded me of is how violent and volatile the band was in the beginning, both onstage and with each other. As Roger notes in the doc, he relied on his fists a lot to do his talking back then. And Keith would bait him into fighting. Then there was the infamous smashing of their instruments during concerts and the setting off of bombs. The Who also had an angry streak in their music with songs like “Substitute” and “I Can See for Miles.” It was apparently encouraged by Lambert and Stamp, who spent a lot of money they didn’t have to replace all those guitars.

Their creative output was an extension of that sort of brilliant and turbulence of the relationships.

I did learn some stuff I didn’t know before, including that it was Chris Stamp who came up with the idea for Roger to stutter while singing “My Generation.”

He was a street-tough East End yob. He knew about kids on amphetamines (popular with The Who’s Mod followers) and how they would talk with a stutter.

Also, Pete’s art-school roommate Richard Barnes (author of “The Who: Maximum R &B,” an authorized history of the band, who appears in the doc) came up with the name The Who. And that Pete countered with the very terrible The Who and the Hair.

Thank God, Pete did not get his way every time.

I also forgot that Kit and Chris started their own record label, Track, so they could work with Jimi Hendrix, who already had a manager and producer. They were behind his first album, “Are You Experienced.”

When they met Jimi, they said, “Hey, we will manage you” and learned that role was spoken for. Then they said, “We will produce you.” But that role, too, was taken. So what they could do was offer him a recording opportunity. They also did his first single, “Purple Haze” backed by “Hey Joe.”

Probably the most erudite contributor onscreen is Richard Barnes. He has one of the best lines when he jokes about Kit’s incessant chain smoking: “We think he used one match his whole life to light the first cigarette.”

He was terrific, wasn’t he? We went about casting the film and found the characters who most represented the essence of the story, not necessarily the ones with the best information. My production partner, Loretta Harms, had dinner with Barney, as he is called, and found him to be quite amazing. He also had an observation about the “Quadrophrenia” album (the band’s second rock opera about Mod culture that didn’t click as strongly with U.S. fans). He said, “Everybody bought it. But no one played it. When you were hanging out, no one would put it on the turntable.”

Why did you decide to make Kit and Chris the subject of your directorial debut? And devote 10 years of your life working on the documentary.

Chris and I formed a colleague relationship over conversations about a Keith Moon biopic he was trying to get off the ground. I was a young cinematographer with some success with cinema verite movies and we shared similar unorthodox views about music and filmmaking. We had creative discussions about how we saw the Keith Moon film being shot. That project ultimately did not go where film projects have to go. So, in 2004, Loretta and I approached Chris about doing a film on him and Kit. It was a rare story, an untold story. One of the greatest untold stories in rock and a rich subject. Being someone who never stood in the way of the creative process, Chris went into shock. Being a consummate pro, he knew it would be an enormous undertaking. He did ultimately think it was a good idea. He rang back and said, ”I’m willing to put myself through it.” We soon after had lunch with Roger and Pete, and began shooting in London in 2005.

There were often colorful impresarios behind many of the top rock acts. It might have started with Elvis and Col. Tom Parker. The Beatles had Brian Epstein. The Rolling Stones were in league with Andrew Loog Oldham and Allen Klein. What made Lambert and Stamp stand out?

It’s a love story. A gay-straight story, too. Very complicated. They had these smiles. You just trusted them when they came at you. They swept you up into the chaos.

It’s fitting that you close the film with Roger and Pete getting recognized at the 2008 Kennedy Center Honors. And Chris going along with them.

There is an irony and paradox in that. When they started, The Who were thought to be so confrontational, anti-social and against the norm of the day. But anything done with truth and conviction stands the test of time and is embraced on more and more levels. I am glad it ended where it ended. Chris Stamp’s monologue at the end, that was his story, that was the situation he was in. It felt like closure and an opening.

Have Pete and Roger seen the documentary yet?

Unfortunately, they couldn’t make it when we premiered the film at Sundance. I will catch up with them on tour. After the premiere, though, they did call and gave their congratulations.

One last question. If Kit were still alive, what would you have liked to ask him?

I would probably ask him what the greatest question is to ask anybody. He seemed like someone who always had a look on his face, as if he were questioning and probing, waiting to ask a question. Actually, I would have liked to ask him what I asked Chris about him: What did he see in Chris? That would make it complete.