Gene Siskel dreamed of getting into one of the legendary poker games Johnny Carson held in his house in Malibu. He thought Carson would be a masterful poker player, able to send signals and conceal them with such facility that to watch him would be an entertainment and an education.

It was that way on the Tonight Show, too. Carson was always completely and serenely at home on the show, night after night and year after year, and he was a superb interviewer: Sympathetic, a good listener, quick with zingers, putting himself down rather than his guests. And yet when you watched for years, as I did, you could read his mind, or you thought you could, and the signals he was sending told you whether he thought his guest was holding a good hand or not.

The first time Siskel and I were invited to appear on the Tonight Show, the evening began badly. “We do not belong here,” Gene told me in the dressing room, as we heard Doc Severnson and the orchestra playing the show’s theme. “We are Midwest boys from Chicago and we belong in Chicago right now, this very moment, watching this show on television.”

A writer popped his head into the dressing room with a last-minute thought: “Johnny might ask you about some of your favorite films this year.” The writer left. Siskel and I looked at each other in horror. We were terrified. Our minds went blank. At that moment I could not think of a single title. “Name a film,” Gene said. “‘Gone With the Wind’,” I said. “Me, too,” Gene said. He called our office in Chicago and said, “Quick, tell me the names of some movies we like.”

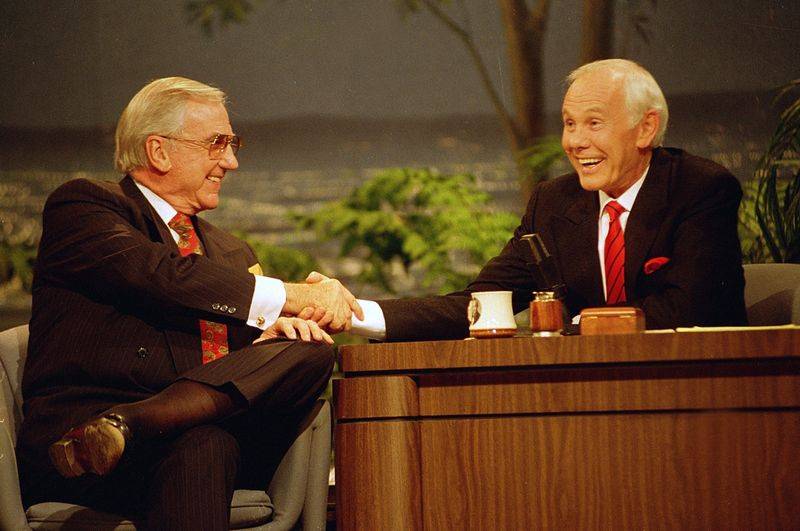

Then the moment of truth arrived, we marched out onto the stage just as if we were real Tonight Show guests and not pathetic imposters, and you know what? It was okay, because Johnny made it okay. He projected an aura of welcome and calm. There is no other way to describe it. We were not pinned like butterflies to a corkboard, being watched by millions, but simply sitting there on the couch talking to Johnny, who was talking to us as if it were the simplest thing in the world.

Carson’s gifts were limitless. His skits and his characters, his slapstick and gags and funny hats and costumes, came from inexhaustible comic energy, but he never overplayed his hand. He was cool beyond cool. He made Sinatra seem to be trying too hard.

On one show, an awkward moment took place. Chevy Chase had been the first guest, promoting his holiday movie “Three Amigos.”” Now Gene was in the chair and I was on the sofa, and Chevy had moved down one, next to me. After five or six minutes that went smoothly, Johnny looked straight at me and asked, “Roger, which of the new Christmas movies do you like the least?”

In one heart-stopping moment I knew that the only honest answer was “Three Amigos.” I should have found a way around that answer, but I could not. “Three Amigos,” I said, looking, I hope, as miserable as I felt. A strange energy enveloped all four of us. “Looking forward to YOUR next film,” Chevy said, which broke the ice, and then Johnny said, “I wish I hadn’t asked you that” and I said, “I wish you hadn’t, too.” After the show, Chase told me he disliked the movie, too, but that wasn’t the point. Then Johnny popped his head around the door. “I asked you, and I got my answer,” he said. “Good television.”

Off-camera, Carson was cordial to his guests, but kept a certain distance. By comparison, Jay Leno walks into the dressing room, sits down, and tests his monologue on you. David Letterman believes everything should happen for the first time on the air, so he avoids even seeing his guests before they come onstage. Carson was affable, amused, welcoming, but a little detached, because we were not his personal friends, and he wasn’t one of those showbiz types who treated everyone like an old buddy. That was the job for Freddy DeCordova, his longtime producer, who sat just out of camera range beyond the sofa and communicated with Johnny in the telepathic way a catcher works with a pitcher.

I watched Carson for hundreds and hundreds of hours of my life. He was a performer born for the medium of television. When he retired, nobody really believed he was gone for good. Everyone thought he’d be back, as a guest, or in a movie, or hosting the Oscars, or somewhere, somehow. But he wasn’t. He retired, and enjoyed his private life, and that was that. A great poker player knows that you lose if you stay in the game too long. There is a right time to walk away with your winnings, and your memories.