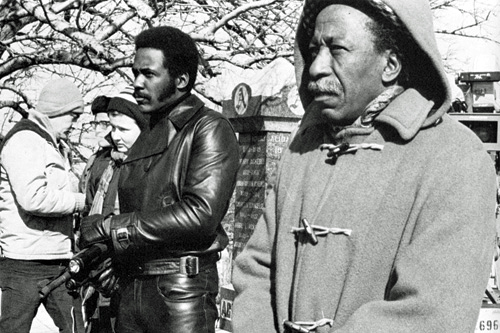

For Gordon Parks, the first black director in the history of the Hollywood film, it all began more than 30 years ago when he was an assistant bartender on the North Coast Limited between Chicago and Seattle.

“I went to see a newsreel about the bombing of the Panay, an American gunboat in China,” he remembers, “and there was this terrific footage by a man named Norman Alley. And then the lights went up and there was Norman Alley himself on the stage, talking about how he’d stayed at his camera position while the bombs were falling. That made a tremendous impression on me, and before long I was thinking of photography as a way to express myself.

“I bought a book about photography and read it on the run to St. Paul and Seattle. When I got to Seattle I had some pay coming and I went to a pawnshop and bought my first camera. It was a Voigtlander Brilliant. It cost $12.50. I took it down to Puget Sound to photograph some seagulls, and damned if I didn’t fall into the water — but I held onto the camera!”

Those first photos still exist, and were included in an exhibition of Gordon Parks’ work by Eastman Kodak. And there were countless other exhibitions, as Parks developed during the 1940s into one of the world’s greatest cameramen. For many years, he was a staff photographer for Life magazine, then the most coveted job in America for a photographer. And he did other things, too, that made him something of a Renaissance man: He wrote poetry, composed a concerto, five sonatas and a symphony and wrote his best-selling autobiography, “The Learning Tree.”

But he never directed a movie. “Until a few years ago,” he says, “blacks didn’t even dream about getting into movies, except as actors. It was a closed world, sealed off by discrimination.” Then, in 1969, “The Learning Tree” was bought by Warner Bros.-Seven Arts.

“Ken Hyman, the president of Seven Arts, liked my book and knew my photography. We had a meeting that lasted 15 minutes and he gave me the job of directing ‘The Learning Tree.’ All of those years of prejudice and bigotry were broken down in 15 minutes.”

Since Parks became the black pioneer behind the camera, several other blacks have directed – among them Ossie Davis, Sidney Poitier, Bill Cosby, Yaphet Kotto and Melvin Van Peebles. But Parks’ “The Learning Tree” remains, to this day, the only non-exploitation film directed by a black. All the others (including Parks’ “Shaft” and “Shaft's Big Score,” now at the Roosevelt) have depended on sex, violence and action to sell. “The Learning Tree” was a deep and humanistic portrait of growing up black in America.

“I like ‘The Learning Tree’ better than both Shafts put together,” Parks says. “It’s a movie about people, complicated people, and of course it has a lot of me in it. After this second Shaft film, I’m pulling out of black films as such. That doesn’t mean that I wouldn’t want to direct a good movie about black history, if the right screenplay came along. But I don’t want to be typed as a black action director. I want to try my hand at all kinds of films.”

His next project, tentatively scheduled to shoot in the fall, will be about the turmoil in the days just before World War I, and will star Peter O'Toole and Vanessa Redgrave. (“It centers around the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand and the events leading up to it.”) He is also negotiating with George C. Scott for “Bank Shot,” which he describes as a comedy caper.

Although he doesn’t want to direct the further adventures of John Shaft, black private eye and superhero, that doesn’t mean Parks is putting Shaft down.

“People come up and ask me if we really need this image of Shaft the black superman. Hell, yes, there’s a place for John Shaft. I was overwhelmed by our world premiere on Broadway. Suddenly, I was the perpetrator of a hero. Ghetto kids were coming downtown to see their hero, Shaft, and here was a black man on the screen they didn’t have to be ashamed of. Here they had a chance to spend their $3 on something they wanted to see. We need movies about the history of our people, yes, but we need heroic fantasies about our people, too. We all need a little James Bond now and then.”

Richard Roundtree repeats his original starring role in “Shaft’s Big Score,” but because John Shaft is a man of few words the principal dramatic role in the movie probably belongs to a Chicago actor, Wally Taylor.

“Wally was our mainstay,” says Parks. “He originally tested for the role of Shaft himself. He wasn’t big enough, but he had a good test. Then just two days before we were set to go on ‘Shaft’s Big Score,’ our second lead, Nathan George, called up and said he wanted equal billing with Roundtree.

“He thought he had us over a barrel because it was too late to change the casting. But it wasn’t. I got on the phone to Wally in California and told him to get on the first plane East. He arrived on Sunday and by Monday his script was dog-eared, he’d studied it so thoroughly. He was great. And the crew loved him because he did all his own stunts – never used a double or a stunt-man.”

Roundtree did most of his own stunts, too, Parks says, including all of the driving in the speedboat chase. “He racked himself up against a stone wall once, but he kept driving. That made it easy for us. We could get close with our helicopter shots because you could see it really was Roundtree and not a stunt driver. We spent 12 days on that chaser, and wrecked four cars, two boats and a mock-up chopper.”