BELEM, Brazil The speedboat came churning too close to the big barge holding the lights and camera, and everyone could see what was going to happen. The wake slapped against the barge and rocked it, and the tall scaffolding swayed back and forth. And then slowly, with an expensive majesty, the $18,000 light toppled over and sank to the bottom of the Amazon.

“Sure, I felt bad when I saw it go,” Saul Zaentz said. “But I would have felt worse if I had to call somebody in the States and explain it to them.”

Zaentz is the boss down here on the location of “At Play In The Fields Of The Lord,” the new film he is producing in the middle of the Brazilian rain forest. The movie’s locations are as difficult as it gets in the movie world. One set has been constructed in the middle of the jungle, a day’s trip by water from the nearest city, and the actors are living in an old tourist boat anchored to the shore. Daryl Hannah observed with a grin that her room on the boat is half as big as her hotel bathroom.

It’s hot and it’s humid here, and there is a thunderstorm, every day, like clockwork. There are snakes and tarantulas and creatures that can eat you with one bite, and others that can devour you with a million tiny nibbles. But strangely enough, this is a happy location, perhaps because everyone thinks the movie might have a shot at greatness. Two of the last three films Zaentz has produced have won the Academy Award for the best picture. They were “One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest” (1975) and “Amadeus” (1984). The third was “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” (1988), which was also of Oscar caliber.

What people respect about Zaentz is that he runs his films single-handedly. A white-bearded man of about 60 who made his fortune in San Francisco in the recording industry, Zaentz chooses books and plays that challenge him, and then makes them into films on his own terms. “He doesn’t answer to anybody,” said John Lithgow, who plays a veteran missionary in “At Play In The Fields Of The Lord.” “That’s the most extraordinary thing about him. The dailies don’t get sent anywhere for anybody else’s approval, and cost overruns are not being monitored by a bunch of executives thousands of miles from here. He owns it all. He does it the way he wants it. It’s incredible how that affects every aspect of production. I’ve really never worked with anyone like him.”

And when an $18,000 light topples into the Amazon, Zaentz sighs and hopes the insurance will cover it. The fact that he is present on the location every day helps keep up the spirits of the others who are sharing these difficult conditions with him. Here they are in the rain forest: Lithgow, Hannah, Aidan Quinn, Kathy Bates, Tom Berenger and Tom Waits, making a movie about missionaries, Indians, corrupt backwater officials and faith in several varieties of God.

The movie is based on the 1965 novel by Peter Matthiessen, who told of two missionary couples who come to the jungle to convert the Indians. In the wretched little regional capital of Madre de Dios, they find Guzman (played by José Dumont), the district commandante – an obscene, drunken bully whose plans center around bombing the local Indians into submission so that the jungle can be opened up for commercial exploitation. Guzman hopes to use two renegade Americans to carry out his plan: Wolfie (Waits), a savage knife-fighter from a big city, and Moon (Berenger), an Indian torn by guilt because he has never lived up to the traditions of his people.

Wolfie and Moon are mercenaries who have escaped Cuba one step ahead of Castro, have sold themselves and their battered 1950 DeHavilland aircraft to despots and dictators up and down the South American coastline, and who have arrived in the province out of money and gas, with no place to go. In the Matthiessen novel, the commandante confiscates their passports and demands a bombing mission as the price for their freedom. The missionaries get wind of the plan and oppose it, ineffectually. And sexual and personal tensions grow.

The key scene in the movie is one where Moon, flying low over the jungle, sees an Indian defiantly shoot an arrow at the plane. This vision so enraptures him that later, lost in a cloud of drugs, he parachutes into the jungle and joins the tribe, where he is accepted as a god.

This is a good story to make a movie from. It has elements of “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” and “The African Queen” and “Farewell to the King,” and addresses the current passion over saving the rain forest. The novel has been announced as a project by several filmmakers over the years, from John Huston to Arthur Penn, but at last Zaentz got the rights and signed the Brazilian director Hector Babenco (“Pixote,” “Ironweed“) to direct it. And now here they all are, headquartered in Belem, 100 miles upriver from the mouth of the Amazon and surrounded by rain forest. This city had a boom time when the rubber trade took off in the 19th century, and there’s an opera house still standing as a memory of that time, but today it is a picaresque backwater, large and lively but not prosperous.

Zaentz has headquartered his actors and crew in the Belem Hilton, where the buffet in the dining room headlines a different “international cuisine” every night. Outside of town, he’s built two locations: Madre de Dios has been created as an elaborate shanty village on both sides of an Amazon tributary, and the mission station has been hacked out of the rain forest a day’s trip upriver.

It’s easy to get to Madre de Dios. You pile into a motorboat and head upriver, the banks of the Amazon presenting a green wall of thick tangled trees and vines. Here and there a space has been cleared for a small house and a dock – the Indians here commute by boat, not road – and presently you make a wide arc into a river tributary, and see a colorful village built along both sides of the water.

This looks like a real village, and it should, because Zaentz and his art designers have purchased real buildings, taken them apart, and moved them here. There is a church and a row of saloons and rooming houses, and a large red tooth hangs as a shingle outside the office of the dentist. After you climb up onto the dock the first stop is the fetid darkness of the lobby of the Gran Hotel Delores, where Commandante Guzman holds court. I had just finished reading the Matthiessen novel, and its images were so fresh in my mind that it was creepy to see the big chair in the corner where Guzman runs his affairs of state.

The shot that day involved a long walk in the rain by Daryl Hannah, who plays Lithgow’s missionary wife. She walks by the side of the water and into a church, oblivious of the rain, her soul torn between the faith she professes and her growing doubts. Although Belem is one of the rainiest places on Earth, it does not always rain, and so fire hoses on scaffolds were used to make the rain as she walked again and again, her blond hair slicked wet against her face. In charge of the shoot was Babenco, an expansive man who, judging by his appearance, will choose breakfast over shaving every time.

He and Zaentz stood in the shade of a veranda jutting out over the water, and followed every shot on a video monitor. Hannah, who seemed to enjoy her regular showers, consulted with Babenco after each take, and then went back to her starting place. It was a difficult shot from a technical point of view, because rain doesn’t photograph well and must be meticulously lighted.

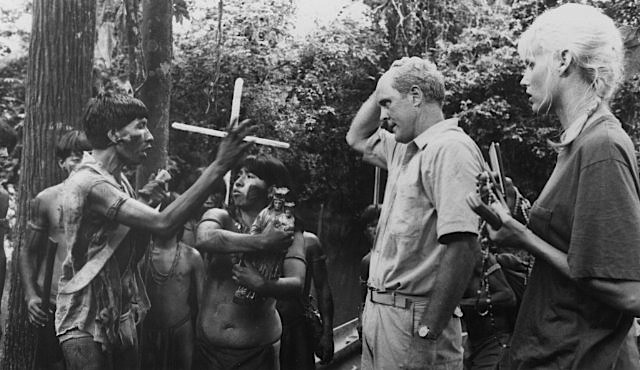

Babenco sat down and accepted a cup of lemonade from one of two people assigned to circulate all day with cold drinks; dehydration is a danger in these tropics. He talked about the expeditions into the rain forest he and Zaentz took while trying to find locations and Indian actors for the film. At first, he said, they went far into the rain forest, visiting tribes that were still relatively untouched by civilization. But it seemed wrong to disturb them with the demands of a film production. So they looked closer to Belem, to Indians who were in a transitional state between their villages and the city.

“It was an experience,” he said. “We gathered 65 or 70, and we worked with them for four weeks. We rented a little ranch about an hour and a half from here. We put everybody naked, as they used to be in their own villages, and we started to reactivate their cultural memory. I know this sounds a little pretentious. I don’t know even how the result will be.

“For instance, the Indian who is playing Aeore, who is the most important Indian in the movie maybe, was found in a road station in Brazil. He was waiting for money to go back to a little town where he could get a ride to get to his village. For three or four days, he was sleeping on a bench in a road station, and this is a guy who has a main part in the movie.

“The lady who’s playing the old lady is a local Indian who lives here with her three children. Her husband died, and she works washing clothes for some rich family, where she goes in the morning to get the clothes and brings them back at night. She has been living in Belem for five years. She is 53, she looks 70. She is somebody who has spent almost all of her life in her Indian village.

“Since the day that they came to work with us, these people, they have been guests of the production. They are living with us. There is no way to send them back. They have no addresses. They don’t have telephone numbers. There is no way to send them a telegram, or a telex, or anything.” The Indians of the Matthiessen story have their own notions of God and morality, and have little interest in the teachings of the missionaries, whose Christianity seems bizarre to them. In the novel, there is only one Indian who converts – and he does it not out of conviction but because he sees a way to benefit. The Moon character, on the other hand, converts to the Indian ways and eventually ends up leading the Indians in a guerrilla war against Guzman and his ragtag army.

Most of the scenes involving the Indians are being shot not in the Madre de Dios location, which is relatively easy to reach, but in the location which has been built to represent the mission station. It is an hour by air, and the night before we were scheduled to fly there we were sitting on the veranda of the Hilton when a young man named Chris walked up.

“I’ll be flying you folks tomorrow,” he said. He liked the phrase “you folks,” maybe because it sounded the authentic folksy note that pilots like to use. “We’re flying a DeHavilland Beaver. Built in 1950, but tuned up real nice. This is the plane that opened up Alaska. It’s fitted with pontoons, so if we lost both engines, which is real unlikely, why, we could just glide right down and land on the water and you folks wouldn’t be in any danger at all.”

The DeHavilland Beaver sounded a familiar note, and the next morning when we approached it at anchor in the Amazon, it indeed turned out to be the actual plane that was being used in the movie. The fuselage was painted with a pin-up girl and the words “Wolfie and Moon, Inc.: Small Wars and Demolitions.” We piled in with Chris and Zaentz and took off across the water, bouncing on the waves until we gained air speed, and then turning in a lazy curve out over the Amazon and upriver.

The further we flew, the happier the people along the bank were to see us. The clearings came further apart, but at each one children ran out to wave at the airplane, which was flying only a few hundred yards above the treetops. We circled over another of Zaentz’s sets – the Indian village – and then landed smoothly on the water and taxied over to a makeshift pier at the mission station.

“We had to build everything on this location,” Zaentz said. “Kitchen, mess hall, dormitory, costume and props departments, roads, everything.” He led the way into a Range Rover, which bounced down a corduroy road for half a mile. The rest of the way to the location was on foot through the trees, because of Zaentz’s insistence on being able to turn the camera 360 degrees for any shot. Half climbing, half falling down a muddy cliff, we were at last at the makeshift dwelling that the missionaries would use in their attempts to convert the Indians.

“Have a drink,” said Zaentz. He held out a paper cup of water. For a week I’d been drinking nothing but bottled water and rinsing my toothbrush in Dr. Tichnor’s, but now here was Amazon well water, which Zaentz insisted was as pure as all outdoors. “You won’t die of the runs,” he said. “It’s dehydration that will get you.” Flying back to Belem, we were assured once again by Chris that the faithful Beaver was the safest plane in the air because of its ability to land on the water. I was reminded of that conversation not long ago when I ran into Aidan Quinn in New York. He was on a whirlwind visit to America to promote his new film “Avalon,” in between scenes in Brazil. And he was carrying around photos of the DeHavilland, broken in two and nose-down in the Amazon.

“I thought it was supposed to be able to land on the water,” I said.

“It did,” Quinn said. “Then it ran into the bank.”

No one was killed in the accident, but it underlined the difficulties of making a movie on location. “We could theoretically have shot this movie in a studio, or in a more convenient location,” Zaentz said one day. “But it would have been wrong. This is a movie about the rain forest, and every shot should declare that it is being shot in the place it’s about.” Aidan Quinn and Kathy Baker play a less successful missionary couple who fly down to Brazil to join Lithgow and Hannah, who have built a somewhat spurious reputation for converting legions of Indians. Quinn said it was difficult for him to research his role because missionaries in the area “have all received directives not to talk to us, not to help us, not to have anything to do with this film. So, I went with my North Dakota accent and a green look on my face, and visited some missionaries in San Paolo. They just assumed that we were young children of God, and we proceeded to get lectured by this character who was like Leslie (the Lithgow character). He had all these fatuous anecdotes and was very full of himself, and then this guy came in who was more like Martin (Quinn’s character, ineffectual but more thoughtful and sincere). Finally, the Leslie character said he had to go, and he turned to Martin and said, `This is the real man of God.’ This guy was interested in preserving the Indian’s culture, preserving their dances, and not just promoting North American cultures.

“There are quite a few missionaries, although they are still in the minority, who are rebels. Instead of bringing in vaccines and playing the great white father, they’ll give it to the witch doctor, and let it be his idea. Then it really takes.”

There was a chance to talk with all the actors one night when they had dinner together in the apartment of a crew member whose wife was a gourmet cook. The weekly “gourmet dinners,” Lithgow explained, were a way to keep up morale, which would be especially shaky when the company made its big move to the mission station.

“I think they’ll fly us back to Belem for one or two nights a week,” he said. “The rest of the time, we’ll be living pretty rough. I think it’s going to be very hard, but I think it has to be that way in order to achieve what we’re after. I read the script, and I thought this was going to be a very rough time, but I suppose acting is such a martyr’s game. You want to participate in something where you’re really taxed, where you’re taken through this journey. I can’t imagine this movie being done anywhere but someplace in South America, with this kind of hardship. It’s like, it has to be done that way. You can’t simulate this in Southern California.”

Let’s say it’s 110 degrees in the shade one day, I said. You have something you feel very strongly about in terms of your character. You’ve been here for a month, and you have dysentery. At what point does your ego cave in, and you just want to get the thing over with? Or do you persist in what you believe in?

“Oh, I think I would persist. It’s an interesting thought, because you do have those feelings – for God’s sake, let’s get this over with. There’s no question about it. We haven’t really been subjected to the toughest times yet. We’ve all gone into this project believing two things. First, it was a worthwhile thing to do, and second, it was going to be incredibly difficult. Once you accept those two things – embrace one, and accept the other – I think you’re just in a different frame of mind.

“I’d be a much crankier actor in the comfort of a luxurious backlot in Hollywood than I am here. Besides which, you’re working with 50 other people who are working under the same circumstances. It makes you feel very egalitarian. Everyone is suffering. Of course, it’s murder when you spend an entire day waiting around on a boat, and then you’re told that we’re wrapping, without having even gotten one shot. Those are hard days, but I’m used to that.”

He was holding a guitar as he spoke, and now he strummed it absently.

“I’ve brought lots of things with me to keep myself interested,” he said. “I have my guitar. I’ve been doing a writing project. I brought oil paints, My philosophy is, take something along that you would rather do than act. That way, when they finally say they’re ready for you, you don’t want to go.”

I doubt that Saul Zaentz took anything along, because I don’t think there is anything he would have rather been doing than making the movie. When the others give him credit for running the whole show out of his back pocket, they are telling the literal truth. He doesn’t even have a unit publicist on his film, but meets a visiting journalist’s midnight flight himself. He stops in at an office where computers keep track of the shooting schedule and budget; he circulates in the hotel lobby when cars are picking up cast and crew members; he signs checks in the dining room and leaves notes for people about what’s coming up tomorrow. And he tells stories.

“You just missed Tom Waits,” he said. “Tom got to the airport and had forgotten his passport, and went back to get it, and almost missed his flight, and was convinced they sent his luggage down the chute without a tag on it. So he jumped on the conveyor belt and rode it right down to the luggage room, right through the rubber flaps. He was surrounded by airport security in a second. They thought he was a terrorist. We almost had an international incident.”

Zaentz smiled. He hadn’t had to telephone anybody about that, either.