Saturday

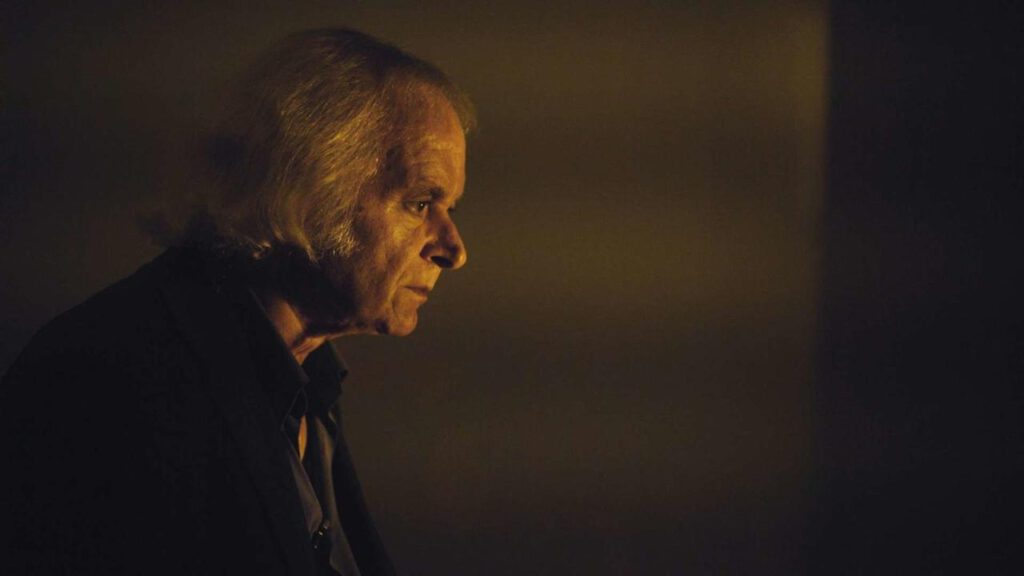

An odd, disquieting film about negotiated desire, Cristina Haneș’ “António e Catarina” explores the tender, somewhat fraught relationship between the director and a much older man named Augusto. Haneș frames Augusto in tight, intimate shots over the course of three years as he openly longs to be with the younger woman behind the camera. He asks teasing, uncomfortably forward questions about her boyfriend and her sexual history, frequently testing the limits of their relationship, while Haneș, mostly off screen, humors him. In between his explicit yearning, Augusto expresses regrets about his life, and ponders openly about his inability to maintain lasting relations with women, platonic or otherwise (though one gets the sense that the man can’t sustain relationships of any kind).

Haneș’ brisk feature stands in firmly melancholic terrain: Augusto’s lonely, wistful eyes dominate the frame, even as his mouth produces consistently lecherous material. There’s a role-playing element to the author-subject relationship; they call each other by different names (António and Catarina, respectively, hence the film’s title), ostensibly to channel their respective emotions into a persona distant from their own. Haneș raises obvious questions about power imbalances in relationships, especially with relation to age as well as sex, but I’ll confess that aspect doesn’t interest me all that much. It’s partially because “António e Catarina” hints at those ideas rather than really sussing them out, but mostly because the conversations/monologues are plenty entertaining on the surface that their subtext largely falls by the wayside. Some might call that a failing, but for me, “António e Catarina” doesn’t need the extra weight to sustain the interest. (Note: Mileage will inevitably vary based on one’s patience with harmless, yet relentlessly dirty old men.)

A former Marine assigned as a Combat Camera in Afghanistan, Miles Lagoze was supposed to shoot and edit recruitment videos for the Corps, but he ended up leaving the camera on and filming more than he needed. He eventually assembled his footage along with those of his fellow cameraman into “Combat Obscura,” an inside look at daily Marine life on the frontlines. The results are somewhat expected, but nevertheless engaging: the Marines shoot the shit and smoke Afghani hash in their off time, but when they’re on duty, they search for Taliban operatives among innocent civilians and engage in frequent firefights with a faceless enemy. Lagoze foregrounds various contrasts between professionalism and adolescent shenanigans, violence and relative peace, readiness and boredom, all while depicting the psychological vigor one must maintain to get through days in a war zone.

Some of the specific footage disturbs, such as the centerpiece sequence when the unit must transport a fellow Marine with a fatal head wound onto a medevac chopper before it’s too late, but it’s the frontline immersion that will plague the emotions more than anything. “Combat Obscura” raises the necessary point that soldiers are expected to otherize their enemies and adopt an aggro, emotionally detached exterior in order to be combat ready, an uncomfortable idea for peaceniks and armchair liberals alike to swallow. How much can one chalk up, say, the accidental murder of an innocent shopkeeper, or unnecessary harassment of a group of Afghani mourners to “war is hell”? Lagoze doesn’t explicitly pose questions like that in the film, choosing instead to let them percolate in the background amidst the noise. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that there are plenty of casually funny moments in between the horrors that feature Marines as overgrown kids, another discomfiting idea that Lagoze puts forth regarding who exactly we send to do our government’s dirty work. (In that respect, “Combat Obscura” brings to mind David Simon’s great, underrated miniseries “Generation Kill,” which dramatized similar ideas and situations about Marines, albeit from a civilian journalist perspective.)

Far and away the best film I saw at True/False, Leigh Ledare’s “The Task” positions itself as a provocation, something designed to rankle and frustrate audiences, especially those suspicious of, or prematurely exhausted by, modern identity discourse. But “The Task,” which debuted as an art installation piece in Chicago late last year, doesn’t exist to push buttons or push hollow ideas, even if it’s trying to examine Who We Are. Instead, it’s a fascinating, dispiriting examination of the cultural dialogue in today’s hyper-aware political climate, and how the necessary work one must put in to better understand personal biases and prejudices can also engender circular misunderstandings. Do large group settings foreground our differences more than our similarities? Are human beings inherently inefficient communicators? Is the search for greater insight into our diverse human landscape an unproductive one? These are the compelling questions at the heart of “The Task.”

After a brief overture establishing the makeup of a large room, the film’s sole setting, and a survey of the camera operators assigned to film the proceedings, Ledare throws his audience into the thick of an unspecified conference at the Art Institute of Chicago. At the conference, a diverse group of people that make up a cross section of the population are tasked with decoding and examining group dynamics. Some of the participants are named during the film while others are not (a running gag involves people repeatedly asking one another to identify themselves). There are rules in place as well as goals to be accomplished, presumably, though Ledare never explicates what they are. There are “consultants” who are supposed to lead the conference, but they’re never explicitly identified. Ledare keeps most of the pertinent “how” and “why” details purposefully vague, so much so that one might wonder why these people are in attendance at all.

However, Ledare’s goal, at least for the theatrical audience, is to engage with the larger conversation, in which participants interrogate, defend, and question each other’s behavior, actions, identities, and quickly enough, the fundamental premise of the conference itself and “The Task” as a film. Examples of such spirited interactions include an Asian woman who tearfully explains why she feels she has to censor herself because of systemic oppression dating back to her ancestors helping to build the railroads, only for an elderly white man to interject that the Irish also helped build the railroads; fierce debate over whether people are undermining an attractive woman who assumes a position of power at the conference because she’s attractive and a woman, only it’s unclear what power, if any, she holds over the group; and frequent assertions that the presence of cameras are hindering the group’s progress because they’re either unconsciously performing or silencing themselves. Eventually, events take a turn for the worse when Ledare, a silent observer for the majority of the conference, officially enters the group, throwing the conference into minor chaos.

Influenced by the Tavistock method, a psychoanalytic approach devised in the 1940s that strives to investigate group survival, “The Task” functions, in the words of Ledare, as a “microcosm of our collective culture.” Anyone who has ever spent time in a college common room, let alone a Facebook comments section, will likely recognize the types of intense debates that occur in the film. Participants at the conference frequently invoke the phrase “in the here and now” as a grounding force for what they might accomplish, but “The Task” illustrates the upward battle of investigating the present through self-examination. Many interesting insights are shared, some worthier than others, but little is accomplished. Everyone is supposedly on the same page in terms of shared goals, but no one can seem to get through to each other. People talk, but it’s unclear if anyone says anything. At one point, a frustrated participant, who hadn’t spoken before and will not speak again, throws his hands up and openly ponders how human beings ever evolved out of the caves. I cannot express to you how often I’ve had that exact same thought after spending a day on the Internet. For some, “The Task” might be a maddening thought exercise, but if it should receive a theatrical release, it will be the one film that will live up to the “Now More Than Ever” promise of relevancy that so many less worthy films try and fail to embody.

Sunday

After days of watching fairly depressing work, a film like Anna Frances Ewert’s “Lovers of the Night” feels like a salve for the heart. Ewert’s film follows seven Irish monks who live in a Cistercian monastery in the Irish countryside as they go about their daily routine. We listen as they explain why they entered the monastery, we watch as they tend to the farm and the cattle, but most importantly, we witness their strong devotion to a cause bigger than themselves. It’s unclear if the monks are just the last of a dying breed, or if they’re elder statesman simply waiting to pass their wisdom onto the next generation.

Ewert’s film has a casual, understated charm because her subjects are genuinely sweet people who have stories to tell, but also because Ewert herself functions beautifully as a conduit for their stories. The monks’ palpable comfort with Ewert allows them to open up about their origin stories (surprisingly, none of them were particularly devout before entering the monastery) and their various fears and regrets. One monk in particular presents an alternate timeline of his own life where he became a professional Rugby player, but a crucial loss sent him on his current path. Ewert frames the countryside as a placid, but necessarily solitary place, an ideal environment for the monks to live out the rest of their lives. It’s rare to see people at peace with their own existence in a tumultuous world, but it’s even rarer to see them bring such lighthearted humor to their own relative insignificance. They’re mirthful men of God who wish nothing more than goodwill for themselves and others before their time runs out.

RaMell Ross’ “Hale County This Morning, This Evening” was the last film I saw at True/False, and in terms of sheer ambition, it’s a fitting end to a festival that strives to break new ground in creative nonfiction. An experimental documentary that chronicles the lives of two young black men living in rural Alabama, Ross examines the southern black experience beyond narrative confines, which tends to be weighted down by hegemonic symbolism that merely serves to flatter majority-white audiences. “Hale County” follows Quincy Bryant, a young father, and Daniel Collins, an aspiring basketball player, over almost a decade as they face life’s various trials and tribulations, but Ross doesn’t superimpose any trite character arcs that render either subjects metaphors for Black Life in America Today. In fact, Ross doesn’t even try to make explicit parallels between the two stories. Instead, he lets a poetic eye lead the way and equally foregrounds both the mundane and the dramatic, allowing his subjects’ humanity to shine through first and foremost.

In his post-screening Q&A, Ross discussed how he wanted to “bring the black banal into a commercial space,” and that goal more or less plays out in “Hale County.” Ross focuses on offhand moments in Daniel and Quincy’s lives—Daniel diligently shooting baskets at practice, a casual exchange at a drive-thru, Quincy’s child running up and down a living room—but he also frequently hints at the historical shadow that hangs over the land. In the film’s most powerful moment, Ross invokes archival footage of blackface performer Bert Williams during an eerie trip to a crumbling plantation house, illustrating how specters of the past linger well beyond their lifespan. The scene eventually turns into a burning tire bonfire on the dilapidated property, a cathartic fire that attempts to cleanse the rotten soil, but will inevitably come up short. Some of Ross’ lyrical imagery can lean towards the obvious, especially in some of the early match cuts, and there are times when the film’s meditative energy proves tedious instead of provoking thought, but “Hale County” mostly succeeds in its aims to adjust the structures of black depiction on film. May other films set their sights just as high.