The Toronto International Film Festival, a bellwether for the awards season, typically invites a certain kind of film: prestige period pieces, serious dramas on heavy subjects, and especially biopics. This year offers three wildly different kinds of biopics an eccentric Victorian set tale concerning one man’s love of cats, a famous actor’s modest childhood within the religiously divided city of Belfast, and a miniseries about a politically passionate quarterback. They show the wide eclectic range that can sometimes spring from what can be a rote genre.

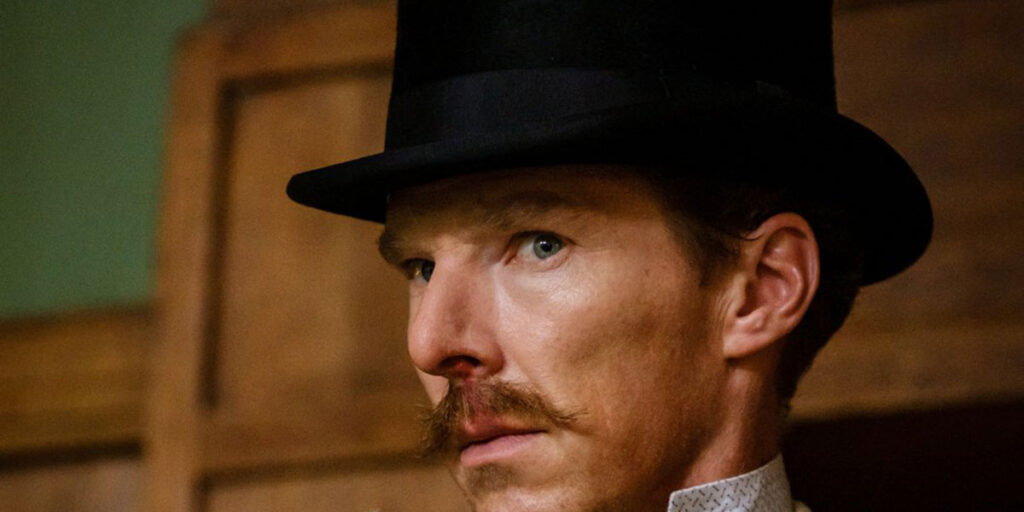

Director Will Sharpe’s quirky biopic “The Electrical Life of Louis Wain” shouldn’t work. Opening in 1881, the film follows Louis Wain (Benedict Cumberbatch), a gifted but troubling eccentric illustrator careening through the social mores of Victorian England in search of love. Following the death of his father, Wain is tasked with caring for his five sisters and aging mother, but is wholly unsuited for the position. Unlike his taskmaster sister Caroline (played by an icy Andrea Riseborough), Wain would rather pursue his varied creative outlets: composing terrible operas and drawing animals for pennies on the dollar, than concern himself with finances.

The peculiar Louis falls for his sisters’ governess Emily Richardson (Claire Foy), causing great scandal due to their opposing social statuses and Emily’s spinster’s age. But Louis cares little for idle gossip. Emily accepts his depressive thoughts—a recurring nightmare sees him drowning on a storm-ravaged ship—his cleft lip, and his physical oddness. Cumberbatch lays the artifice on thick as Louis, crafting the character as a mound of overbearing mannerism. For that reason, the first half of this movie is all over the place, with disparate tonalities that depend on Chaplin-inspired vaudevillian physical comedy from the slender Cumberbatch.

Sharpe also relies on hyper-stylized aesthetics: distracting lens flare, infrared tints, wildly swinging camera work, etc. while Olivia Colman provides witty voiceover narration to actualize Louis’ disintegrating mental state. When tragedy strikes the illustrator, his only solace against the unbearable grief is his pet black-and-white cat Peter. Inspired by his feline companion, Louis gains worldwide fame by fashioning a long-running series of anthropomorphized cat cartoons (this is a film made for cat lovers). Taika Waititi and Nick Cave make cameos, and Toby Jones is a calming influence as Louis’ editor.

“The Electrical Life of Louis Wain” is extremely flawed, and rarely makes any logical or tonal sense. Even so, you can tell how much Sharpe identifies with Louis. That connection gives this bizarre biopic its strange heartbeat. “The Electrical Life of Louis Wain” is just an exceptionally sincere piece of filmmaking.

A brightly lit, colorful montage of aerial shots captures present-day Belfast, mostly the shipping yards where the Titanic was built. The array of images play with the uniqueness of a Chromecast screensaver before a harsh transition takes us back in time to a black and white 1969-set residential corner of Belfast. Buddy (Jude Hill) skips down the street, waving to his cheerful, salt-of-earth working class neighbors. It’s an idyllic scene of an apparent, tight-knit neighborhood, that is blown asunder by an approaching mob. The rioters are the first sign of The Troubles, and are composed of Protestants. They want the local Catholics out.

In this destruction-laden scene, director Kenneth Branagh relies on every visual cliche in the book: the soundscape of explosions is overcooked, flattening the intended heart-stopping effect to a permanent flatline. The camera does an obnoxious 720 rotation around Buddy as he stands in the middle of a melee composed of punishing wooden clubs and smashed windows. Branagh’s “Belfast,” a personal story for the writer-director, contains little dramatic momentum, and even less of a coherent visual language.

“Belfast” is about a disintegrating way of life: Buddy’s parents are fighting because his Pa (a serviceable Jamie Dornan) is in debt to the taxman, and his mother (Caitriona Balfe) can’t seem to pay it off. Judi Dench and Ciarán Hinds are charming as Buddy’s grandparents, a bickering old couple. Buddy has a crush on the smartest girl in school. And every day he and his family are being asked to choose sides in this local religious skirmish. These compelling narrative components aren’t enough to propel “Belfast,” a film chock-full of saccharine pieces but devoid of deeply felt stakes.

Colin Kaepernick was once a Super Bowl starting quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers. Now he’s out of the league. It’s not for lack of talent. Kaepernick had all the attributes NFL franchises look for in a QB. Those qualities were ignored when he took an action the NFL despises, the one unwritten rule—he became political.

In 2016, before the 49ers fourth preseason game, Kaepernick unleashed a maelstrom when, in protest of police violence against Black people, he kneeled during the national anthem. Berated as un-American by many, as a “thug” by Donald Trump, he hasn’t played a snap of NFL football since that season. In that time however, he became a symbol for the Black Lives Matter movement, and a passionate activist decrying police brutality. Now he’s teaming up with director Ava DuVernay for a six-episode Netflix-Array series entitled “Colin in Black and White,” to recount his life.

Co-written and co-executive produced by Michael Starrbury, Kaepernick serves as host and moderator. He can be stiff: in the DuVernay directed premiere his voice overbears the importance of the subject matter. Still, he looks the part, a suave range of black overcoats and his robust afro form a great profile. He discovers great ease as a narrator, providing heartfelt recollections of how his emotional response to certain events, such as his parents’ want for him to cut his hair rather than keep his Allen Iverson-inspired cornrows. Some of the series’ best moments have the action on screen freezing, only for the camera to pan to Kaepernick watching the action unfold from a minimalist set, reacting to their import.

The show aims to have several directors helm the varying episodes: the second, for example, was led by Sheldon Candis, and the third by Robert Townsend (“Hollywood Shuffle”). The topics covered include: the origins of the word “thug,” microaggressions, and white privilege. Mary-Louise Parker and Nick Offerman are a winning pair as the QB’s racially illiterate parents. And Jaden Michael as the young Kaepernick gives a detailed performance, offering slight variations in his delivery to impart his calm, sorrow, and belongingness. “Colin in Black and White” is subversive and provocative, bearing passing similarities to DuVernay’s “The 13th”—it’s brisk, witty, and sweet, and offers a thoughtfully constructed critique of America’s racial history and present.