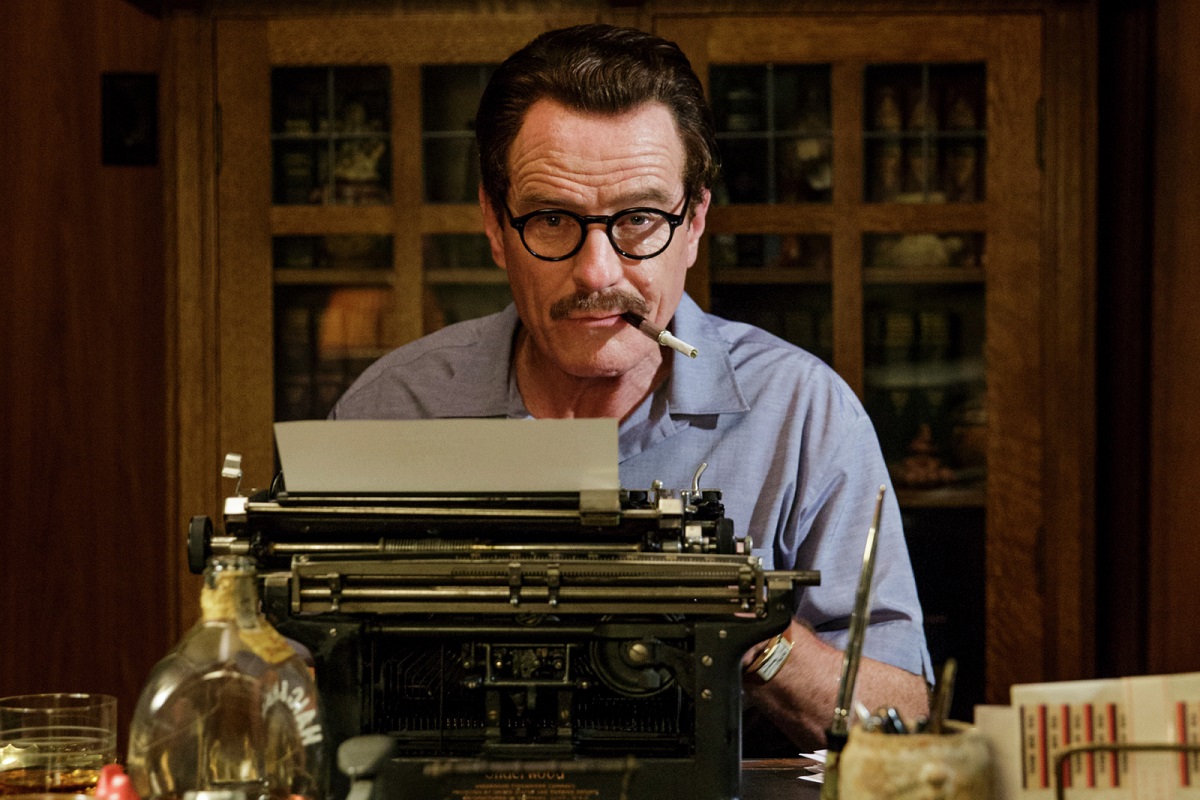

Dalton Trumbo (Bryan Cranston), after being sent to prison,

with his career destroyed by the blacklist, is brought a script by Kirk Douglas

(Dean O’Gorman). The matinee idol tells him that he’s attached to the project but

that the massive screenplay for “Spartacus” needs some serious work. He says something that

Trumbo will quote later about another script—“There’s a good story in there somewhere.” Rarely does a film give

you such a distinct quote to so easily apply to itself. Jay Roach’s “Trumbo” contains an undeniably strong

story at its core, and Cranston does nothing wrong here, but the film feels artificial and staged when it needs to feel heartfelt and passionate. It’s one

of those works that, from scene one, is telegraphing its sense of importance to

the viewer. Every line, every scene, every beat is weighed down with a sense

that the filmmakers value message over character, period detail and even

filmmaking. The message of Trumbo’s story—that we should never punish people

for that which they believe—is a timeless one, and one that bears repeating

throughout the years in various forms of fiction. But Roach and screenwriter

John McNamara’s approach is leaden, thumping and pushing viewers to its themes

instead of letting them come organically.

From the very beginning, storm clouds are on the horizon for

screenwriter Dalton Trumbo. It’s mere minutes into the film before his daughter

asks, “Dad, are you a Communist?”

Newsreels of Trumbo rallying protesting workers in Hollywood play before a film

and the writer gets doused in sweetened beverage in the lobby afterwards. The

tide is turning as the Cold War intensifies, and the word Communist takes on

new meaning for Americans. It is not a different belief system, but that which

will take us down from inside. The Red Scare is fueled by hatred and

misunderstanding, represented by several people in “Trumbo,” including Hedda

Hopper (Helen Mirren), who uses her column and clout to force studios to fire

Communist screenwriters, and even John Wayne (David James Elliott), who

preaches intolerance for anything anti-American. Trumbo and his Communist friends,

including writer Arlen Hird (Louis C.K.) and Edward G. Robinson (Michael

Stuhlbarg), plan to fight back. They refuse to answer questions in front of

HUAC, hoping that their case will rise all the way to a liberal Supreme Court,

where they will be vindicated. In the middle of their journey, a justice dies,

and they know they’re in trouble, as the political balance will now shift. In fact, Trumbo and other members of the

Hollywood Ten are sent to prison for contempt, and their home lives and careers

come tumbling down.

When Trumbo emerges from his incarceration, it is to a completely

different world. No producer is willing to put his name on a screenplay. The

movie won’t get made if people know Trumbo wrote it. So he starts to work

behind the scenes, not only because he’s still got the immense talent to do so,

but because he needs to feed his family (Diane Lane plays his wife, Elle

Fanning his now-grown daughter). He essentially turns his brood into a script

doctor workshop, covertly receiving scripts, working on them (often in his

bathtub), and then sending them back via messenger. He does his most work with

the King Brothers (John Goodman and Stephen Root), helping tweak their B-movie

cavalcade. He also happens to write “Roman Holiday,” which he gives to a

colleague (Alan Tudyk), which wins the Oscar for Best Screenplay, and “The Brave

One,” which he writes under a pseudonym, and wins as well. It’s not until Kirk

Douglas and Otto Preminger come to Trumbo that it looks like he may finally be

able to emerge from the shadows.

“Trumbo” is about freedom of belief. It needs to be

passionate, intellectually engaged and confident. I’m not sure if Roach was the

wrong fit or McNamara the wrong writer, but one never senses a pulse in “Trumbo.”

It’s missing the human element, the beating heart that kept Trumbo, and others

like him, going. Dialogue is stilted, forced and Hollywood. There are a few

scenes between Cranston and Louis C.K. in which it feels like we’re actually

watching two friends relate, but too much of “Trumbo” is lacking that humanity.

More than half the dialogue is thematically purposeful. This is one of those

scripts in which people talk about what they’re doing and why they’re doing it

in nearly every scene—you know, like no one in real life.

It’s also a fatal mistake to frame the film as flatly as cinematographer Jim

Denault and Roach chose to do so. Some people have accused it of looking like

an HBO movie, but films like “Olive Kitteridge” and “Mildred Pierce” had a much

stronger visual language. This film has none. It is box framing, pointing the

camera in the direction of the action.

The Red Scare and the Hollywood blacklist are shameful chapters

in this country’s history. Lives were destroyed over paranoia and belief. It’s

a story that’s not taught well in schools, and a film like “Trumbo” could bring

it to a wider audience. I do believe there’s value in learning from our

mistakes as a country. And writers will always fascinate us, especially those

for whom it would have been so easy to give up, but they chose not to. What

drove Trumbo to keep writing when it felt like the forces pushing against him

were unstoppable? The film that bears his name never answers the question satisfactorily.

Still, there’s a great story in there somewhere.