There was a squirrel’s life between me and the edge. It was late May and my sister and I were driving down the tree-shaded road leading to my father’s house. My mother’s car is a big, graceful ride, so we took our time. Truth be told, rushing was beyond us.

For reasons fathomed only by acorn-obsessed minds, the squirrels kept dashing—kamikaze—into the road, dodging our mother’s tires only by the skill of my sister’s turning of the steering wheel.

“Please don’t hit them, Shaina,” I whispered, scanning the road for misguided scamper missions. “I don’t think I can take it.”

I knew—the way we know things in moments that stutter and can’t be explained—that my sanity rested solely within the madness of squirrels and my sister’s ability to turn the wheel just so. My hands gripped the dashboard, and I asked my brother, “How?”

I saw my British Aunts, Mona and Corinthia, that week. It was the first time in over half my life, and I loved them like it was genetic memory, loved them instantly—again. They were mine and I was theirs and they held my mother, sister, and me together like space-aged epoxy. They couldn’t mend us but they held strong so we could start to heal ourselves. During the nights I stayed with my mother in her room, neither of us sleeping, both of us silent, and I asked my brother, “How could you?”

My father cried that week. I had never seen it before.

They all cried that first day at Russell’s Funeral Home and I sat there. Rubbing their backs and patting their legs, chastising myself with, “Where’s the superhero you’ve always imagined yourself to be? Huh? Find her why don’t you.”

Later, in my mother’s front yard, a bee buzzed around my head. Insistent. I don’t speak the language so couldn’t understand. I listened anyway, then let the wind lick my face and asked my brother, “How?”

We wore orange for ‘the’ day. I don’t remember the date. Perhaps because I’ve always been very good at not doing things I don’t want to. Perhaps because May 27th, 2006, is burned indelibly into my skull. Other dates have no purchase. Orange is a color of joy and it seemed right. In the back of the limousine, I stared out at my hometown, a city rich with southern hospitality, culture, art, sassiness, and familial bonds reaching back through generations. I was not pleased with my city that morning, but I could do nothing—only wipe my face. Swipe at wet cheeks and try to smile. Reach out and squeeze someone’s hand, then turn back to the window.

When we went inside, I paused at the top of the aisle. Took a deep breath and because my brother may have been there somewhere I asked him, “How could you? How could you drown?”

Tarik had always gotten out of any—even the most desperate—situation unscathed. He was better than Houdini. It didn’t make sense. Maybe it never will.

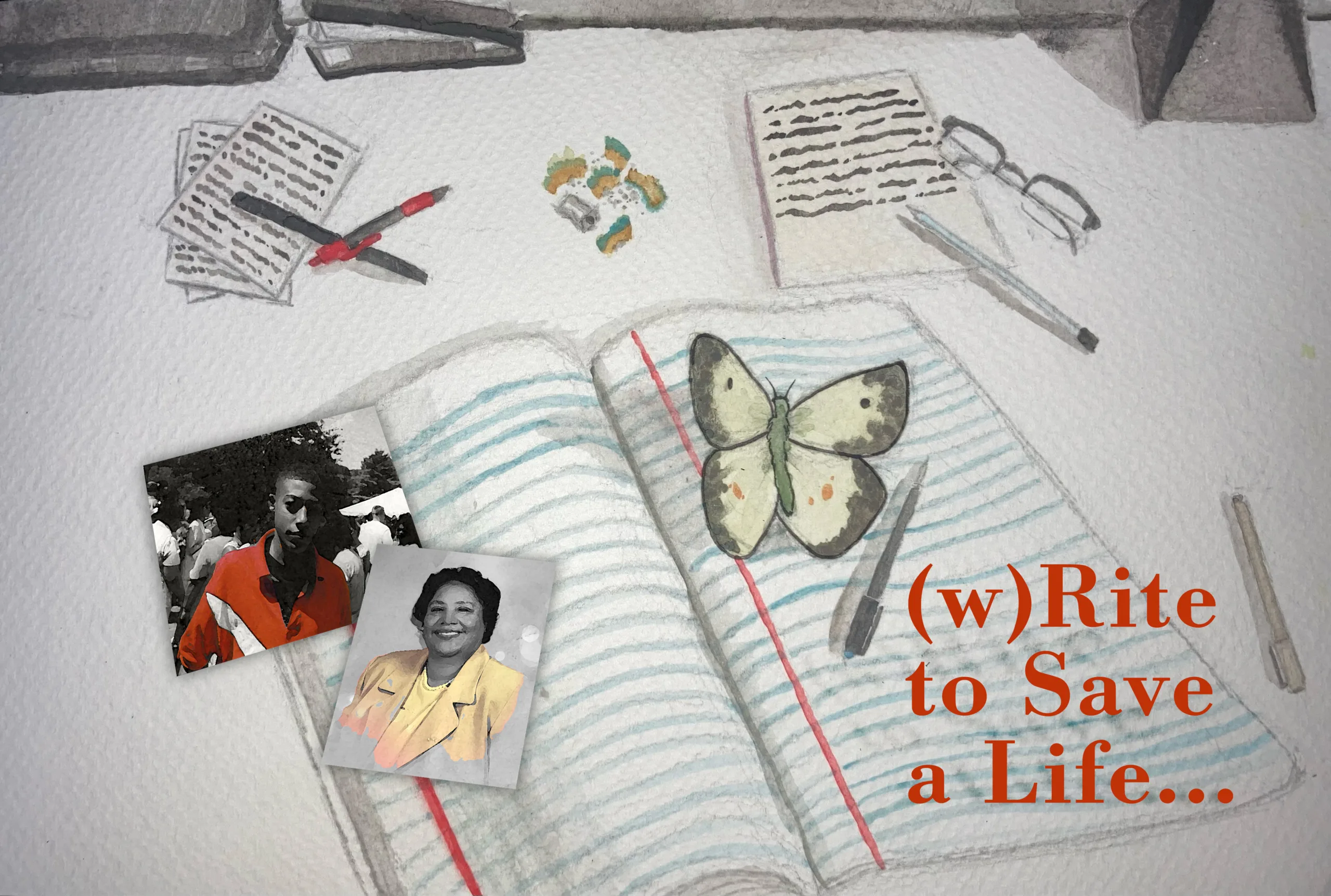

When I looked down into the coffin, I knew his soul was gone. What remained here was only a cocoon, a shelter for the soul’s metamorphosis. The butterfly had flown.

The following week I stumbled down the dock at Mallard Lake, leaving my shoes behind me. Silence plugged my ears. Nothing moved. Nothing breathed and I felt stuck between that moment and the one that would eventually follow. Having reached the edge I sat down, closed my eyes, and prayed. I prayed. I prayed and when I looked up there was sunlight dancing metallic on the dappled lake. A golden butterfly with black tips to its wing floated like hope over the water.

“Look, Sherin!” my Aunt Sylvia said, “A single butterfly, a spirit freed! He’s letting us know he’s okay.” I wanted to hug her as she stood beside me weeping, but I didn’t feel alive…until…the lake…burst…into sound.

Three ducks flew a slow graceful arc and landed like faeries on the golden waves. Bugs sang buzzing symphonies, and we cried, my aunt and I, while her little sisters, the Twins, stood silent vigil.

That night my mother went into her garden, drawn to the spot where my brother used to fumigate her plants with his cigarettes. At first, she thought it was a moth, that fluttering of wings at the periphery of her vision, but no. Instead, dancing like sun at midnight over my brother’s smoking spot was a golden butterfly with black tips to its wings. A spirit freed.

Three months later I began to write. Not for the first time but this time in earnest. I wrote the things I had reserved for ‘one day.’ Now had become paramount and one day seemed foolish to await.

Writing was solace. It blocked the quickening of dark dread that dogged my every thought. I worried constantly for the health and safety of those I love. Although not as frequently, I worried just as much for those I like.

I read and watched movies almost as much as I wrote. I’m an escapist so I had to go someplace beyond the rule of mortality. Fiction did the same job it had done in my childhood. Words were wings.

2006 did not relent. A shooting. A brain aneurysm. A death so sudden it seemed the skipping of a heart’s beat and then gone. On New Year’s Day, another death after cancer refused to let go. Requiems seemed a steady soundtrack. And even as I rejoiced in the recoveries from bullets and blood vessels, I struggled limping yet hopeful into 2007.

Good thing pens make great crutches.

***

May is a difficult month. On Mother’s Day, my mother’s memories linger on the last one she spent with my brother. He woke up that morning and decided he wanted to go to church. So, they did. The Church Ladies kept saying how handsome he looked in his suit. He and my mother must have beamed those identical smiles. Smiles that reflected their connection to each other and the joy of the moment. Today and in every May, Mother’s Day is wrenching. Only a week after that good day at church, Tarik transcended this world. May 27th, three months before his 25th birthday.

Life x Death is an equation we cannot solve.

365 days later, my mother’s other best friend, a tiny gray Shi Tzu called Yuri, died from an aneurysm. The timing aligned with the anniversary of my brother’s death. May…again. I ached for my mother, and I simply ached.

That morning, a dog’s life hurled me back into mourning. Back to the lake, to the end of my brother’s life on earth, to Bonnie Raitt singing “God Was in Water That Day” like a message the afterlife couldn’t return to sender. Perhaps that’s why my mother and I hold a particular affection for “John Wick.” We understand how the loss of a dog can replicate the loss of the loved one it’s connected to. We relate to the duality of that peculiar existential entanglement.

Seventeen years later—after five deaths in five weeks—the end of 2023 did the same. My friend Leon, a man who defied being defined, departed this dimension on the night we made plans for a next week that cannot come. Four weeks after that, my auntie-friend Ruth, a poet and a painter, transcended shortly after the morning she woke up and couldn’t get out of bed. I was at a wedding at the time. Life’s endings and beginnings are forever entangled.

6,833 days later, I can’t hug my Aunt Sylvia anymore. Not like I leaned on her when her beloved nephew, my brother, died. Not like I did when a bitter situation sent me into her arms. Another Mother’s Day arrived, this time in 2025, and I don’t know how to reconcile myself to life without her here. A woman who, for me, is as analogous to life as breathing. I ache for my family, and I simply ache. And yet, that morning, we welcomed a new baby boy into the world. Endings and beginnings are forever entangled.

Life x Death is an equation we cannot solve.

In “The Life of Chuck,” Stephen King and Mike Flanagan paraphrase Walt Whitman, “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes.)” Unknown parts of me died with those loved ones, with Tarik and with Sylvia. Yet they live in me. I guess “The Lion King” got that right too. Writers get it, they see us. Don’t they?

I stand here on tiptoe and flailing; my pen dug deep into the precipice; a lever and a place to stand to keep the world from tilting. I know mine is not the greatest of pains, but it knows me. One day at a lake shattered me. One morning a dog’s life rekindled that pain. One Sunday multiplied the hurt. Again. Thousands of days afterward, life persists in unpredictability. Yet love remains a self-renewing resource.

The numbers will continue to rise, until I follow them, but I’ve solved that unsolvable equation: Grief is the cost of loving into perpetuity. I guess even an android like The Vision could figure that out. “What is grief if not love persevering?” Someone wrote that. Someone understands. So, I dip my spine in ink and create a place to stand to stop my heart from tilting. I choose solace in words—through fiction and in faith. And I write to save a life.

Art Credit: Anna Kim