Whenever I consider short films for the Chicago Critics Film Festival, I usually don’t read up on them before I hit “play.” When I first saw Trevor Anderson’s “The Little Deputy,” it felt like a documentary. The crude VHS quality of the opening shots of a big indoor shopping mall certainly looked real enough to convince me I had been given a very personal home movie re-fashioned into a documentary. I was half-right. It becomes apparent later that we are seeing a reenactment of a memory from a very particular time and place, and it is to Anderson’s credit that he chose to go that extra mile by using a camera from that time period. A digital camera would never have the same effect.

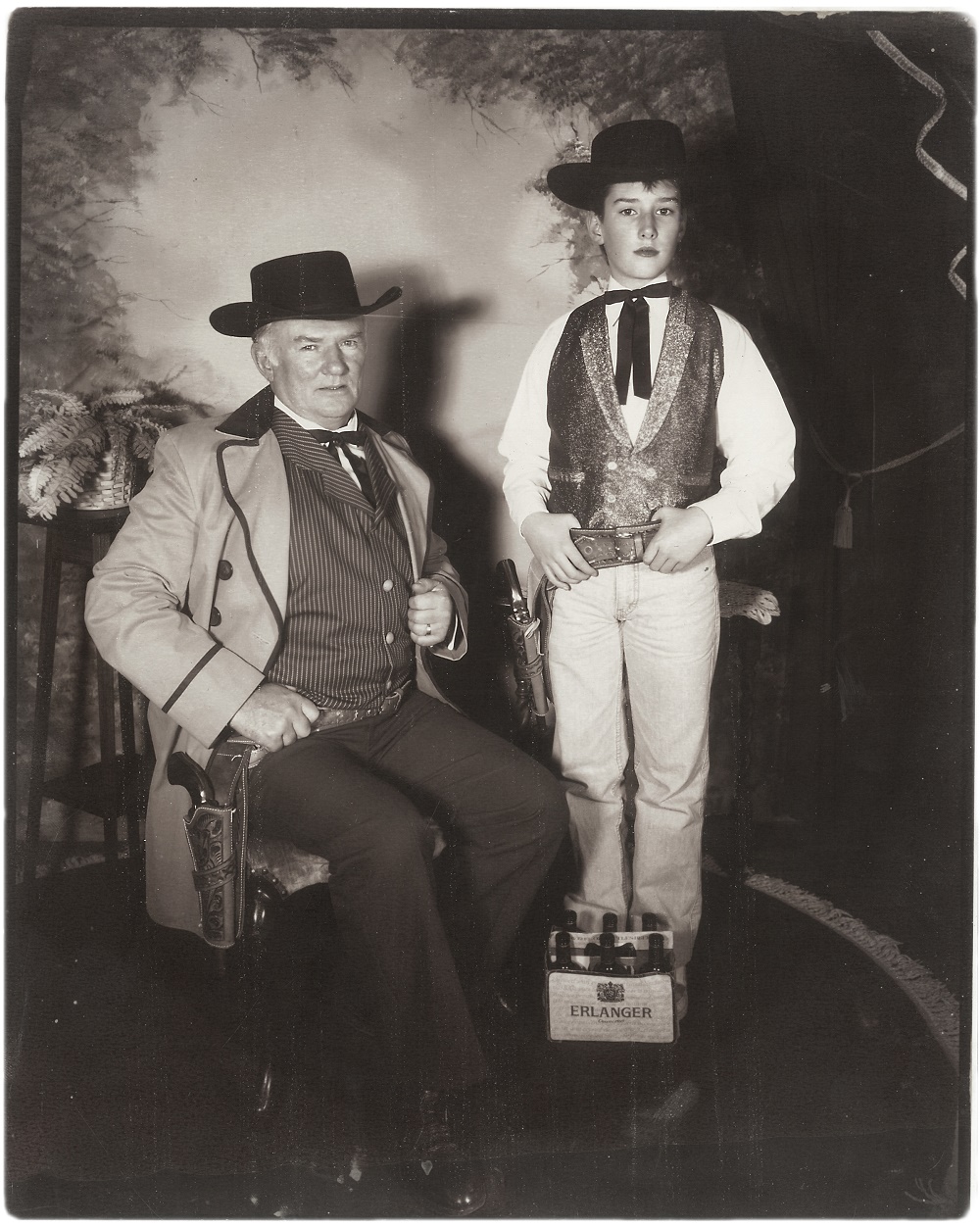

“The Little Deputy” charmingly re-creates a time when Trevor and his father want to the West Edmonton Mall to spend a day together, the very concept of which, Anderson tells us, is a rarity in and of itself. They stop at one of those corny photoshops that dresses people up in old Western costumes and sends customers home with a sepia photo of them dressed as gunslingers and deputies. The man running the store offers the father a sheriff costume and offers the boy a red, sparkly dress. Could this have been a bizarre, momentary oversight on the part of the retailer? Or did he sense something in the boy that nobody could have known at the time, but would manifest itself later in life?

Anderson’s film eventually breaks free from the VHS film stock and goes for a more beautiful, cinematic approach for the present day shots, in which a mistake from long ago becomes corrected as an adult. “The Little Deputy” takes normally heavy-handed subject matter and distills it down to its very essence utilizing different film stocks, concise narration and by choosing to tell the second half of the film completely visually. It’s the best kind of short film, the kind that does not adhere to any familiar narrative trappings, but still conveys something deeply personal that never once feels like an exercise in self-indulgence.

Is this a true story? If not, where did it come from? If so, why tell it now?

Yes, it’s all true. I like to start with a true story simply told, and use that to springboard into wilder filmmaking territory. The first half of the film is straightforward storytelling: I talk directly to the audience about an important day I spent with my dad when I was a kid—a difficult, tricky memory that’s stuck with me—and the second half of the film is me doing something about it; flipping the idea of “documentary recreation” into “documentary creation.” Writing my own life story, changing the story by telling it. Filmmaking as action. I’m contrasting the disempowerment I felt as a little kid with the power I have now as an adult professional artist. My personal filmmaking manifesto is: “Be careful what stories you tell: they become true, and they become you.”

The reveal at the end is wonderful and the film could have ended there, but you chose something different for the final image. What went into that decision?

Thank you. The whole film is about me trying to get a photo taken with my father. I end the movie on an original photo of me and my dad from thirty years ago. This is the document in the documentary. It’s the main promo image, too, so usually the audience has at least glanced at it in passing before they watch the movie. Then at the end, I push in close on it so you can see the whites of our eyes on the big screen, me and my dad, and hopefully you’ll see a little deeper, feel a little more, thanks to the nine minutes of film that lead up to this moment of looking. That same photo hung on the wall of my childhood home the whole time I was growing up—I would stare at it, knowing there was something wrong with it. This movie is my chance to correct the photo without actually altering it.

When I first saw the film, during the opening segment I thought it was a documentary because the VHS footage looked so authentic and the VCR tracking static added a nice effect. Did you use an actual VHS camcorder?

Haha! Well, I do consider it a documentary even though we shot all that footage fresh for this film with, yes indeed, an old, half-busted VHS camcorder we bought off the internet. I don’t like applying false video or film effects in post … why emulate a format when you can just shoot the real thing? That said, my sure-handed editor Justin Lachance was carefully pausing the VCR tape transfer at just the right moments, manipulating it almost like a turntable DJ, to get the right emotional rhythms out of the tracking glitches.

You go from a cruddy VHS look to black-and-white to a gorgeously shot widescreen Western look. What were some of the challenges in going from one extreme to the other?

There are three distinct sections in the movie, each with its own particular “look”: First, VHS footage for the 1986 sequence. I grew to love the look of it—we preserved the 4:3 aspect ratio and even hung it in a black field so you can see the little digital artifacts around the edge of the frame … those details are really pretty to me. We cranked the saturation during the colour grade to give it candy tones. And we shot it shaky hand-held to make it feel like found, archival footage, so that the moment we drop the actors into it, hopefully the audience’s mental needle skips a bit. It’s a surprising little moment that asks you to start questioning your assumptions about what you see … which is what the movie’s ultimately about, I think.

Then, for the present day, we get a second “look” when the picture widens to a very contemporary 16:9 frame, shot on DSLR HD video. Here, you see the “real” me and my “real” mom, but I shot it in black and white as a nod to the fact that this part of the movie is just as constructed as the rest. I mean, that’s not my mom’s bathroom, that’s a set. With a camera crew. The black and white treatment is another gentle alienation strategy. Plus, if I’m shooting my own face that close-up, I’m gonna desaturate it to flattering high-contrast black and white!

The third section is set in 1886 (sorta), shot in Western widescreen, 2.39:1, on an Arri Alexa, with the biggest Hollywood Western production values I could muster. I was lucky to have two cinematographers on this film: Peter Wunstorf shot the big Hollywood-looking stuff—he shot the first season of AMC’s “The Killing” and was Second Unit DOP on “Brokeback Mountain.” And aAron munson, hero of the Albertan experimental underground, shot the VHS stuff.

With three such distinct visual strategies, the sound is what ties it all together. It’s designed by Johnny Blerot, with a deceptively simple original score composed and performed by Canadian guitar god Luke Doucet. That score is all reverse-engineered from the song on the tail credits, which is also by Luke and his wife Melissa McClelland, performing together as Whitehorse. Luke built the score in the same key as the final song, with the same chord progressions, moving from acoustic to electric guitar so it would feel right, inevitable, when the whole band kicks into that great song “Achilles Desire” at the end. A subconscious effect of destiny being fulfilled.

What have been some of the reactions to the film?

My two favorite reactions were when I showed the finished film to my mom on her computer, just the two of us, and she said, “Well, I think you did a very good job, and I sure liked everyone I met that day on set.” That was subtle and sweet. And then there was the Saturday matinee screening to a standing-room-only audience in the gorgeous Castro Theatre at San Francisco’s Frameline festival, where 1,400 queers with daddy issues burst into loud applause two minutes before the end of the film, and kept clapping right through to the end of the tail credits. That was a real heart-stopper for me.

What’s next for you?

After ten shorts in ten years, it’s finally feature time. I’ve made a short musical about my great-uncle’s life, and a short western about my dad. Next: a full-length horror about my fear of dating. It’s called Docking. We’ll shoot the short in 2017 and the feature in 2018. In the meantime, I play drums in a touring rock ‘n’ roll band called The Wet Secrets. Our label, Six Shooter Records, just released an EP worldwide on iTunes called I Can Live Forever, and there’ll be a full album this fall called The Tyranny of Objects.

The Little Deputy from Trevor Anderson on Vimeo.