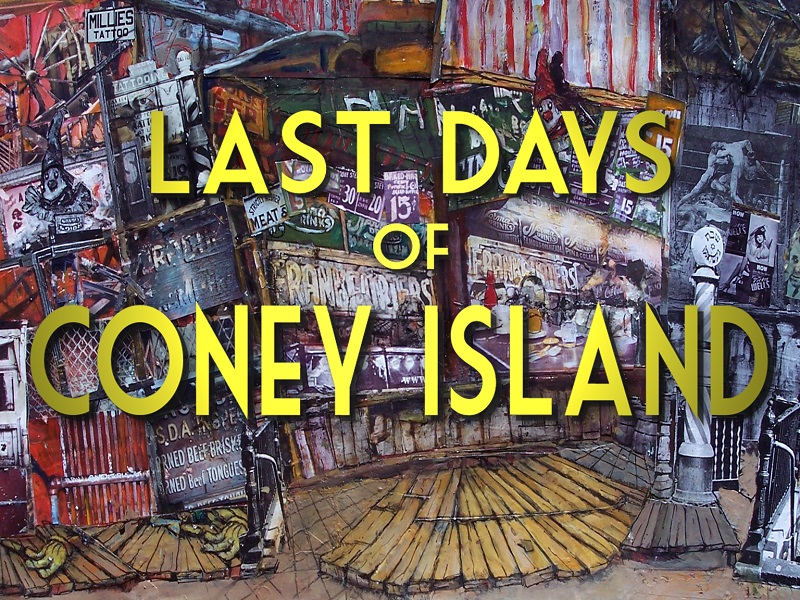

When cult/independent animator Ralph Bakshi took to Kickstarter to finance “Last Days of Coney Island,” a new 22-minute hand-drawn short, his fans’ response was immediate. In six days, Bakshi raised $10,000 more than his original goal of $165,000. This is especially striking since Bakshi’s most recent feature film is “Cool World,” a busy, studio-produced “Who Framed Roger Rabbit” clone from 1992. Since then, Bakshi has worked on a couple of television projects, including the perilously underrated (and short-lived) HBO cartoon noir anthology series “Spicy City,” taught some courses, and sold very few of his paintings. But between then and now, Bakshi’s reputation as an outsider artist has grown exponentially. Last year, Bakshi was celebrated with a retrospective at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Now, two years after its successful crowd-funding campaign, “Last Days of Coney Island” is finally here. Bakshi hasn’t screened the film prior to its the October 29th release date since so much of the film’s meaning comes from its left-turn finale. The 29th is also Bakshi’s 77th birthday.

Born in Haifa, Israel and raised in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn, Bakshi remains an essential, idiosyncratic artist whose creative eccentricities are symptomatic of his stubborn, quixotic personality. It didn’t take long before Bakshi, a rambunctious student at a racially segregated high school for African-American residents of Washington D.C.’s Foggy Bottom neighborhood, developed his drawing skills beyond notebook doodles. After he moved back to Brownsville and graduated with a vocational degree from the School of Industrial Art, 18-year-old Bakshi followed a high school friend to work at Terrytoons animation studios in New Rochelle, NY, where he learned basic techniques of hand-drawn animation.

Television studio executives eventually took notice of Bakshi’s work, and in time greenlit one of his dopier ideas: a superhero serial called “The Mighty Heroes” that supplemented Terrytoons-produced “Mighty Mouse Playhouse” cartoons. But Bakshi soon grew dissatisfied with the quality of the cartoon, and sought out new ways to express himself. That growing dissatisfaction would follow Bakshi throughout his career, and result in several major creative clashes with everyone from underground cartoonist Robert Crumb to American International Pictures distributor Samuel Arkoff.

Bakshi left Terrytoons for a position at Paramount Pictures’ animation division, but that job was short-lived since Paramount shut down their cartoon line down months after Bakshi joined them. With the help of Paramount producer Steve Krantz, Bakshi formed his own studio, Bakshi Productions, whose early financial successes included the 1960s “Spider-Man” cartoon. Of his early Bakshi Productions work, “Marvin Digs,” a rough 1967 short film about a Candide-like hippie optimist, is probably the most significant. There is, however, a reason you haven’t heard of “Marvin Digs”: the film is a negligible stepping stone towards Bakshi’s milestone comedy “Fritz the Cat,” another comedy about a confused counter-cultural type who chases girls, sings songs and generally acts like a goon.

Bakshi left Terrytoons for a position at Paramount Pictures’ animation division, but that job was short-lived since Paramount shut down their cartoon line down months after Bakshi joined them. With the help of Paramount producer Steve Krantz, Bakshi formed his own studio, Bakshi Productions, whose early financial successes included the 1960s “Spider-Man” cartoon. Of his early Bakshi Productions work, “Marvin Digs,” a rough 1967 short film about a Candide-like hippie optimist, is probably the most significant. There is, however, a reason you haven’t heard of “Marvin Digs”: the film is a negligible stepping stone towards Bakshi’s milestone comedy “Fritz the Cat,” another comedy about a confused counter-cultural type who chases girls, sings songs and generally acts like a goon.

Based on Crumb’s cartoons, the Krantz-produced “Fritz the Cat” was Bakshi’s breakthrough project. The film’s sexually explicit humor earned it an X-rating, which was treated as a major selling point by American exploitation distributor Jerry Gross (Bakshi wasn’t so thrilled about Gross’s use of the film’s X-rating throughout the film’s advertising campaign). But Bakshi also wasn’t as naive as Marvin and Fritz either: when he first approached Warner Brothers to make “Fritz the Cat,” he showed them his plans for the ribald (and now infamous) Big Bertha sequence. This was after they offered him $850,000 to make the picture, mind you. Like an explosion from a hormonally-activated id volcano, the Big Bertha sequence was considered too raunchy for Warner Brothers’ tastes; Bakshi was thrown out on his ear, and lost the most lucrative deal of his career because he wanted to be up-front about the type of movie he had in mind.

By the time Bakshi met and talked with Gross, Bakshi’s top priority was getting his film made his way. You can see Bakshi’s attention to detail and tempering of Fellini-esque surrealism with bracing social realism by looking at the film’s photorealistic backgrounds (Bakshi and his team traced over photographs of East Village skyline for these background cels). The film’s unabashedly combustive satire of both authority figures and anti-establishment types was similarly daring. But it was the film’s copious ribald humor, and sexually explicit sequences that made “Fritz the Cat” the most financially successful, independently-financed animated movie.

After “Fritz the Cat,” Bakshi was pressured by Krantz and Arkoff to make more pornographic, talking animal pictures. Since that prospect didn’t thrill Bakshi, he declined to direct the Krantz-produced sequel, “Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat.” Instead, Bakshi made “Heavy Traffic,” an audacious, semi-autobiographical look at a young cartoonist, and his turbulent family life (a Jewish mother and Italian father, hoo boy). Bakshi’s liberal use of taboo-busting racial stereotypes was tempered considerably by his innovative use of ad-libbed dialogue. The film’s explicit, humorously grotesque sexual content earned the film another X-rating, a healthy box office and critical praise from the likes of The New York Times’s Vincent Canby, who called “Heavy Traffic” one of the best films of 1973.

Still, despite his films’ financial success, Bakshi didn’t immediately enjoy the fruits of his labor. He alienated Krantz by demanding Krantz pay him for his work on “Fritz the Cat.” Krantz claimed the movie didn’t make any money, and eventually locked Bakshi out of his studio. Bakshi was re-admitted thanks to Arkoff’s intervention; as arrogant as he could be, Arkoff knew that he was paying for a Ralph Bakshi film, not an adult cartoon by Ralph Bakshi.

Bakshi followed the success of “Heavy Traffic” with “Coonskin,” a controversial anti-fable that combines gangster movie tropes with racial stereotypes taken from minstrelsy, including animated characters that appear in blackface. Like “Heavy Traffic” before it, “Coonskin” featured improvised dialogue, including real conversations between Black Panther members recorded live in Bakshi’s studios. The film’s deliberately crude animation style similarly apes a graffiti style that complicates the racist caricature archetypes used throughout.

Despite playing well with African-American audiences, “Coonskin” understandably didn’t enjoy the financial of Bakshi’s previous two features. Many critics and audiences couldn’t help but see Bakshi’s films through the lens of their controversial content. Still, Bakshi’s films succeed as personal works of popular art, as was made clear by a now-legendary screening of “Coonskin” at the Museum of Modern Art. Al Sharpton led a vocal protest of “Coonskin” outside the theater, and tried unsuccessfully to storm the theater’s stage after it screened. Sharpton’s posse didn’t follow him on-stage; apparently, they enjoyed “Coonskin” too much to attack it.

Bakshi would go on to make a mix of personal projects, like animated musical “American Pop,” coming-of-age story “Hey Good Lookin'” and fantasies like “Wizards” and “Fire and Ice.” Of these projects, Bakshi’s fantasies are perhaps most well-known thanks to their formative use of the rotoscoping technique that Max Flesicher invented on his early “Koko the Clown” cartoons. Rotoscoping, a technique that uses photographs as the basis for cel-drawn animation, is perhaps best employed on Bakshi’s adaptation of “Lord of the Rings,” the 1978 United Artists-produced adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s fantasy trilogy. For that film, Bakshi drew over live-action battle sequences shot in Spain. Spanish film developers quit the production because they didn’t understand Bakshi’s rotoscoping technique, which was erroneously publicized as the first use of a new “moving paintings” style. The film’s developers lost confidence in Bakshi after they saw raw footage of actors, dressed in costume, running around with modern-day cars and lamp-posts in the background. This misunderstanding amuses Bakshi to this day.

After “Lord of the Rings,” Bakshi’s career was about as erratic as one might expect given Bakshi’s fierce independence. After briefly retiring in the mid-80s, Bakshi’s most prominent project was the studio-produced “Cool World,” a far cry from Bakshi’s original vision. Bakshi originally wanted the film—his first feature in nine years—to be more like a horror film. But producer Frank Mancuso Jr.—who was closely associated with the “Friday the 13th” films—did not, and there were significant unauthorized rewrites. Bakshi wound up punching producer Mancuso Jr. in the mouth as result of their creative differences. Bakshi tried to focus on the quality of the film’s Fleischer-esque animation, thinking that would make the experience worthwhile. But he left the project feeling dispirited and disillusioned.

Bakshi returned to television, where he wrote and directed a tantalizing 1994 live-action neo-noir called “The Cool and The Crazy” that starred Jared Leto and Alicia Silverstone, and was developed for Showtime by producers Debra Hill and Lou Arkoff, Sam’s son. But creative mismanagement continued to plague Bakshi’s work. For further proof, see the Bakshi-created “Spicy City.” After a six-episode season, HBO asked Bakshi to fire the “Spicy City” writing staff, a group of non-professional writers that Bakshi was attracted to because of their real-life experiences. This was HBO’s way of controlling the show’s success which, if Bakshi’s to be believed, had bigger ratings than Chris Rock’s comedy specials and talk show. Bakshi walked away from “Spicy City” because he refused to part with his writers. The series was summarily cancelled.

Like other late career comebacks—Alejandro Jodorowsky’s “Dance of Reality” comes to mind—”Last Days of Coney Island” could signal a new phase in Bakshi’s career. During my recent interview with him (look for it here next week), he seemed revitalized. Promotional material for the film makes it look like it was drawn with the kind of crude animation style Bakshi used to complement the rough character of his earlier films’ working-class heroes. Bakshi told me that his recent success with Kickstarter has left him feeling optimistic, and even suggested that he’d like to do a sequel to “Wizards.” With a little luck, “Last Days of Coney Island” will be the first of many new Bakshi films.

Last Days of Coney Island from Bakshi Productions, Inc. on Vimeo.