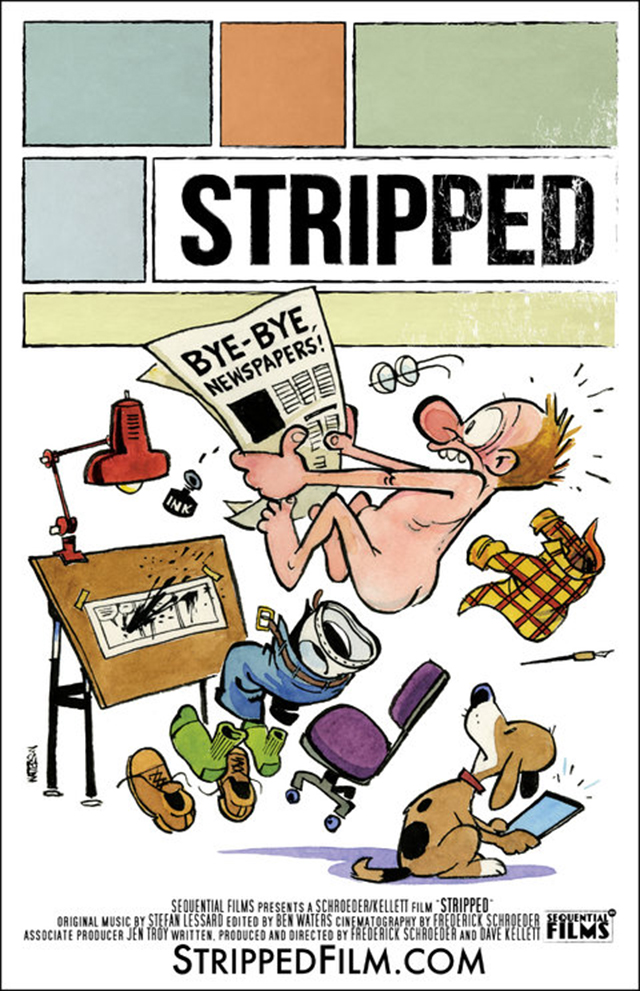

The San Diego Comic-Con Film Festival winner for Best Documentary is a

film that harks back to the original purpose of SDCC—a love for

cartoonists and comics. “Stripped: The Comics Documentary” is about this history of cartoonists

and their comic strips, and how they face an uncertain future. Not to be

confused with the R-rated 2013 horror flick “Stripped,” this

documentary comes in several versions, including a clean all-ages

version, and is available on DVD and VOD on several different platforms.

Other versions available include the “Stripped” Super Awesome Deluxe

Edition which comes with 26 hours of additional content—mostly full

interviews with the participating cartoonists—and can be ordered on the

official website.

Directed and written by Dave Kellett and Frederick Schroeder (director

for “Static” and cinematographer for the TV series “Prom Queen” and

“Heroes: Nowhere Man” and “Chow Ciao! With Fabio Viviani”), “Stripped”

features the first ever authorized recording of Bill Watterson’s voice

(you won’t see his face though) and brings sharply into focus the

problems facing comic artists today.

The documentary begins with a nostalgic, loving look at the Sunday

papers. Remember when Sunday was all about the funny papers? The funnies

were something you could appreciate before you could even read, and, for

some, appreciating the comic strips meant quality time with your father or

mother during a relaxed Sunday brunch.

The voices of several comic strip artists create a mural of memories as

they call out their funny paper favorites. So many of the cartoonists

interviewed recall their fondness of “Peanuts” and others mention

“Garfield.” Younger comic artists recall Watterson’s “Calvin

& Hobbes.”

Yet none of those three strips were from the Golden Age of Comics.

Kellett and Schroeder take us back, using black and white archival film

footage as well as commentary by R.C. Harvey, a comics historian. There

was a time when the writer of “Steve Canyon” (1947-1988), Milton Caniff,

was famous. People knew Rube Goldberg, who drew several cartoon series in

syndication from 1922 to 1934.

We see grainy black and white footage of Chester Gould, the creator of

“Dick Tracy” on the American game show “What’s My Line?” More recently,

Mell Lazarus (“Miss Peach” and “Momma”) appeared as himself on Angela

Lansbury’s “Murder, She Wrote” which ran from 1984-1996.

These artists and others like Al Capp (“Li’l Abner,” 1934-1977) were

celebrities. It didn’t seem so far fetched for the 1965 Jack Lemmon comedy

“How to Murder Your Wife” to have a successful and rich playboy

cartoonist as the central character.

Charles “Sparky” Schulz, the creator of “Peanuts” (1950-2000), is seen

in archival footage and his widow, Jean Schulz, and Jessica Ruskin of

the Santa Rosa, CA-based Schulz Museum. Board member Patrick McDonnell (“Mutts”) is also one

of the prominent voices of this documentary, particularly in respect to

syndicates.

Coming from different social backgrounds, the cartoonists often were

driven to draw by a variety of reasons. Jim Davis (“Garfield) was often

confined because of childhood asthma. Stephan Patis (“Pearls Before

Swine”) had bronchitis as a young boy. They drew to ease the boredom and

loneliness of their days in confinement. Others just had the compulsion

to draw, using whatever they could—even old Christmas cards when

resources were scarce.

Cartoonists were still doing well in the 1970s to the 1990s but cartoon

strips were also changing. Cathy Guisewite began drawing “Cathy”

(1976-2010), bringing to light a new concerns—the everyday life and

angst of the single career woman. Her contract went out to her the same

day her submission came in. Guisewite recalls how embarrassing it was to

show her vulnerable side. Her alter ego wasn’t glamorous and didn’t

have exotic adventures like “Brenda Starr” (1940-2011).

Darrin Bell (“Candorville”), who is black and Jewish, had a less

positive experience, recalling that he was often turned down and advised

he’d do better if his characters were white, animals or children. Bell

is among the new multicultural face of comic strips, and the

documentary includes interviews with Lalo Alcaraz (“La Cucaracha“) and

Kazu Kibuishi (“Amulet” and “Flight“).

Bill Watterson’s “Calvin & Hobbes”(1985-1995) used both children

and an imaginary animal. Watterson broke the more standardized pattern

of regular modular blocks, drawing in a manner more like graphic

novels, but that style has a lot in common with the illustrations for

cartoon strips from the Golden Age.

Once your comic strip was accepted at a newspaper, you wanted to get

syndicated. With a daily strip, particularly one that is syndicated,

you need to produce material every day, reliably. Watterson recalls

that he had “virtually no life beyond the drawing board.” Other

cartoonists talk about how they get inspired to deal with the dreaded

white piece of paper.

Syndication is explained in a 1950s hokey educational segment and we

also hear from the syndicates themselves such as John Glynn and Lee

Salem (both of Universal Press Syndicate) and Brendan Burford (King

Features Syndicate), yet we’re no longer in the heyday of newspapers.

Even then, syndication had its problems too—there seemed to be no room

for new talent. In today’s Internet-using world, there are other

problems. Syndication depends upon selling your strip to many

newspapers; what happens when newspapers begin to fail and fold? About

166 newspapers have closed since 2008. Major U.S. cities used to support

more than one major English-language broadsheet and often a morning and

an evening broadsheet.

If the syndication model is the jewel, then the web publication of

cartoon strips requires either a money manager (e.g. “Penny Arcade”) or

massive efforts in merchandising. One web cartoonist comments that 80

percent of the income was generated through merchandising. The Internet

allows anyone to be an artist and to be involved with one’s audience and

use as much space as one wishes. Yet then we have to strike a contrast

between someone like Charles Schulz or Cathy Guisewite and their

merchandising against hold-out Bill Watterson.

More subtly, the documentary also shows different working styles, the

different media and tools used, including software which is sometimes

combined with actual drawing with pen or pencil to paper.

There is, at this point in time, no way of knowing what the future holds

for newspapers, books or comic strips. Yet the documentary ends on a

positive note, allowing the last panel of Watterson’s “Calvin &

Hobbes” to end the documentary: “It’s a magical world. Let’s go

exploring.”