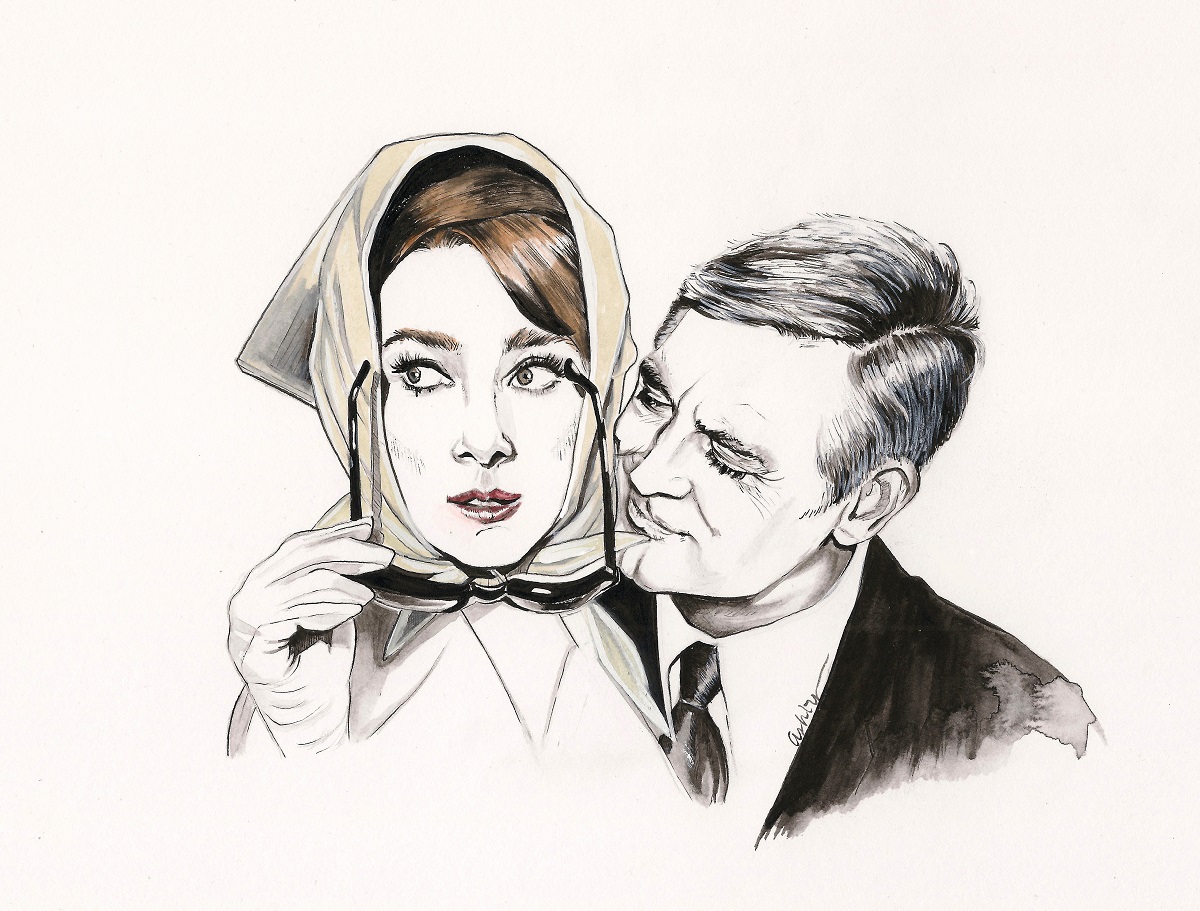

The remarkable team at “Bright Wall/Dark Room” have released their August 2015 issue today, entitled, “Paris,” which includes the following piece by Karina Wolf on “Charade.” In addition, the issue also features essays on “Amelie,” “Before Sunset,” “Breathless,” “Casablanca,” “A Cat in Paris,” “Three Colors: Blue,” “Ratatouille” and “The Razor’s Edge,” as well as a travelogue from film critic Alissa Wilkinson on her time spent watching movies in Paris this summer. Read more excerpts here and you can buy the magazine on your iPhone and iPad here, or sign up for the web-based online version here. The illustration above is by Brianna Ashby.

For the English-speaking world, no star is more essential to

the romantic identity of Paris than Audrey Hepburn. In two of her earliest

leading roles (in Sabrina and Funny Face), Hepburn plays an ordinary

American transfigured by her encounters with the City of Lights. These are Hollywood

fantasies, of course. Hepburn was an untraditional beauty for the 1950s, when

Jane Russell’s curves were the idealized form (even Truman Capote preferred

Marilyn Monroe for the lead in Breakfast

at Tiffany’s). But a spare figure hidden in a gunnysack dress couldn’t

cancel out Hepburn’s knockout cheekbones and alchemical charm. Any cinematic

signifiers of plainness were always a conceit, like a pagan god slumming in a

beggar’s disguise. In a Hepburn film, Paris provides the X-ray vision to reveal

the star as she’s meant to be. If a Hepburn character begins a film humbly, you

are about to be pleasantly shocked — thanks to Paris’s glamorous priorities. If

the starring role begins in elegance and world-weariness, as it does in Charade, the journey through Paris will

reveal the tenderness that underpins Hepburn’s fashionable armor.

Hepburn had a background equal parts privilege and

privation. Her mother was a Dutch duchess; her English father alleged a

hereditary link to Mary, Queen of Scots. When World War II began, her mother

removed the children from London to Belgium, incorrectly thinking that the

Netherlands would remain sheltered from German military offensives. The effects

of wartime malnutrition limited Hepburn’s physical abilities and redirected her

career hopes from dancing to acting. From ballet, she retained an elegant

bearing; from her family, a polyglot’s unplaceable accent; and from wartime

cruelties, perhaps, a lifelong empathy and grace.

She remains the ideal figure to follow through France’s

capital — her sharp silhouette travels well among the grand boulevards and

elegant buildings. Amid the city’s grays and beiges, Hepburn is a pop of color

and enthusiasm. Funny Face makes this

counterpoint most evident when her shop girl character poses in a bright ball

gown, arms aloft, echoing the Venus de Milo, which is perched behind her at the

Louvre. Hepburn is a classical beauty brought to life — both in the symmetry of

her body and the idealized force of her feelings. In Paris, she is vulnerable,

whimsical, unreservedly loving. She animates Paris’s reserved good taste, and

in turn, the city takes on her qualities.

In Charade, we

meet Hepburn’s Regina Lampert at an Alpine resort, drowning in misery. She is

mid-course through a hearty meal and cloaked in a unitard and an ovoid fur cap.

The clothes are by Givenchy, but the effect is more adorable alien than haute

couture cosmopolitan. Regina has a mysterious husband, Charles, now and forever

absent. She doesn’t love him, and what’s

more, she believes Charles is concealing something terrible (spoiler: she’s

right). Regina announces that when she gets back to Paris, she’s getting a

divorce.

Enter Peter Joshua (Cary Grant), stern, dimple-chinned

stranger who returns errant child Jean Louis to Regina and her friend,

Sylvie. “Do we know each

other?” Peter asks Regina. “Why, do you think we’re going to?”

she retorts. In the dialog of Charade,

characters return a question with a question, but somehow everyone gets the

unspoken message. From the start, these

two are engaged in a roundelay of courtship, a pas de deux of interest and

unavailability. The script bubbles over

with playful nonsense:

“You’re blocking my view,” Regina says, face

obscured by cocoa mug and some heavily glamorous shades. The vibe is

adversarial and nonchalant; that is to say, flirtatious.

“Which view do you prefer,” Peter asks.

“The one you’re blocking,” Regina replies in a

deadpan.

Peter excuses himself — he also is returning to Paris later

that evening. Regina isn’t quite ready to let him escape.

“Wasn’t it Shakespeare who said, ‘When strangers do

meet in far off lands they should ere long see each other again’?” she asks brightly.

“Shakespeare never said that.”

“How do you know?”

“It’s terrible.

You made it up.”

*

With Charade,

director-producer Stanley Donen set out to create the best movie Hitchcock

never made. But Hitchcock is all poisoned humor, icy sex, murderous men and

women. Charade is a soufflé — its

characters are light as air, its plot a spun confection. The story’s MacGuffin

concerns the mysterious murder of Regina’s husband, and the rivalry among a quartet

of criminals who hunt for the money he carried when he died. The matter of this

missing fortune accelerates the intimacy between the two attractive strangers,

Regina and Peter. But the

setting—Paris—reinforces the true subject: the delectable, mazy matter of

romance.

In 1963, when Charade was

released, Paris was still dominating artistic cultural conversation. And we find in the film an idealized portrait

of that era’s Gallic good taste—this is the Paris of Sempé drawings and

Bemelmans’ Madeline. Because the picture

is shot in the saturated hues of Technicolor, there is a vibrancy to 1960s

Paris that matches the vivid whirl of the love story. If anything, Charade is a screwball thriller—surely the best movie that Howard

Hawks never made.

Donen was a director who engineered effervescence, a light

touch who guaranteed a giddy feeling. He began his creative life as a dancer

and went on to direct iconic musicals like Singin’

In The Rain. He enabled Fred Astaire’s dance on the ceiling in Royal Wedding by rigging a set that

rotated while Astaire moved.

It makes sense that some of Charade’s best moments are variations on dance. When Peter takes Regina to a nightclub, the

audience is the floorshow—they form two teams and are asked to pass an orange

from person to person without the use of their hands. The fruit is wedged under

the neck of a zaftig older woman, whom Peter approaches with some diffidence

when he sidles up to her body to retrieve the fruit.

When he passes the orange to Reggie, the pair wiggle closer

and we see the couple together as the movie wills them to be—she is fresh-faced

and open; he is arrested by her beauty.

They regard each other for a beat too long, twisting back and forth,

provocatively, and then they separate, in accordance with the game rules. The

mood is further ruptured when one of the villains accosts Reggie on the club

floor and threatens her life for the missing money. This is the dancing rhythm of Charade—fun followed by danger followed by

romance followed by murder. It’s a difficult tone to achieve, this balance

between gentle humor and actual threat, between overt sexuality and demure

courtship. Grant was 60 at the time that the project was proposed, and resisted

the film, saying he was too old to play Audrey Hepburn’s love interest (she was

34). Peter Stone’s script deftly acknowledges the age imbalance: “Stop

treating me like a child!” she cries. “Stop acting like one,” he

tells her.

In fact, in the title, the filmmakers address the biggest

problematic within this charming story, the charade at the center of Charade.

Everyone wants the money Regina allegedly has—the three wartime

buddies of Charles, the CIA bureaucrat played by Walter Matthau, and especially

Peter, who manufactures quite a number of identities to explain how he knows

the other criminals and why he wants to get his hands on Regina’s bequest. Peter’s

deception posits a universal dilemma—it has to do with our identities in love. Who

is Peter really and what are his motives?

Can one know a person if he introduces himself through lies? Is a liar

always a liar? Does someone’s identity remain constant, or is it mercurial and partial?

Is there a moment, at bottom, that all is revealed and it’s possible to make a

judgment?

*

A star is a performer whose craft is projecting the most

appealing and delightful version of himself.

That is not to say that stars aren’t acting or that a star’s performance is

easily achieved—there are few people whose best selves are as charismatic as the

worst days of a superstar. They also tend to be singular in physiognomy—a

caricature of beauty and the ne plus ultra of their type. You can think, for

example, of all the secondary stars who lived in the shadows of their more

compelling counterparts: how Marilyn outstripped Jayne Mansfield and Jane

Russell, how Liz Taylor’s decadence was never equaled by the starlets who

followed her (as recently as the women of Twin

Peaks). They are of their moment and eternal, only themselves but also

transcendent.

Cary Grant had such a powerful singularity, and it was used

by various filmmakers to achieve a positive or negative charge. Grant could

play absent-minded or shrewd, callous or calculating, or aping for a crowd. With

Grant (in contrast with Audrey Hepburn), there’s always a remove. Possibly this is the result of the sheer

technical skill of his performances, the Tommy gun speed line readings in His Girl Friday or the acrobatic tumbles

in Holiday. Perhaps, this vagueness

is inseparable from a self-invented matinee idol who began as a vaudevillian.

In Charade, Cary

Grant works at the perfect intersection of MVP dream guy and menacing mystery.

Is he pretending attraction to Hepburn’s Regina to find the missing money? Is he her ally, or a murderer, or the worst

kind of seducer, one who engages emotionally for selfish gain? We can see the dramatic irony—with Regina’s

husband Charles, everything was secrecy and lies. Now, she is repeating the patterns of her

marriage in this next relationship. Cary Grant is a handsome charmer, but when

he lies about his identity for the third and fourth time—at what point should

she suspect his character, no matter how much he enchants?

“Why do people tell lies,” Regina asks Peter.

“Usually because they want something, and they think

the truth won’t get it,” he tells her.

In Charade‘s final

act, Regina must choose between two allies who have lied to her, and the wrong

choice means her certain death. She stands amid the columns of the Palais

Royal, carrying the missing money, positioned like prey at a shooting gallery

between two gunmen. “Reggie — trust me

once more — please,” says Grant’s character, urging her to take his side. “Why should I?” she cries. “I can’t think of

a reason in the world why you should,” he tells her. The choreography of the scene is schematic—there

is darkness and light, shelter and exposure, danger and safety—but Regina is

not simply a pawn on a chessboard. Her faith in Peter might have arrived

unprompted—the beloved may not have earned her adoration or confidence—but it’s

up to her whether to sustain the feeling.

The ultimate emotional gamble is something that comes easily

to Hepburn’s characters—it’s the ability to be vulnerable without defense. It’s

not a matter of intellect but of intuition. With little proof of his integrity,

Regina won’t let Peter (who is revealed to be Alex, then Adam, then Bryan) out

of her sights. Reflexively, we, the audience, also want them together, no

matter the alarms his duplicity might set off. Hemingway, another Parisian

expat, famously noted, “The best way to find out if you can trust somebody

is to trust them.” In Billy Wilder’s Berlin or Roman Polanski’s Chinatown,

Regina’s faith in Peter might have a more bitter resolution. But in Charade’s Paris, her inclination to

trust pays off in love (and because it’s the early 1960s, in a marriage

license, too). Hepburn’s Funny Face

character sang about the city, “It’s too good to be true / You change my point

of view. / That’s for me. Bonjour,

Paris!” Rosy-colored, optimistic, Charade

and its Paris propose a romantic notion that also happens to be true: the

greatest reward is earned when we lower our defenses to love.