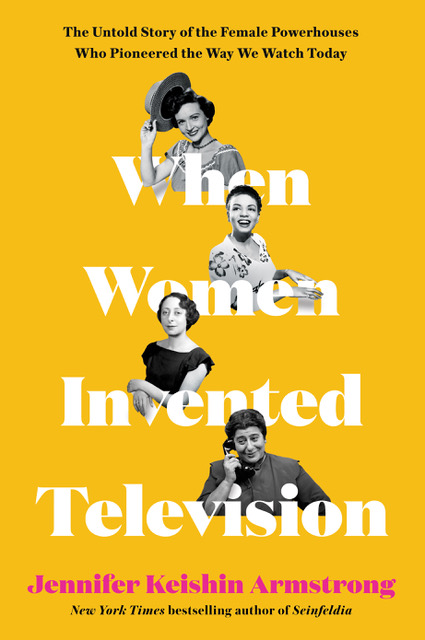

We are grateful to Jennifer Keishin Armstrong and HarperCollins for permission to include this excerpt from her superb book about four women who played foundational roles in the early days of television. Before she was Sue Ann Nivens, a Golden Girl, Hot in Cleveland, and a national treasure, Armstrong describes Betty White as ’50s television all-purpose star on- and off-camera, doing commercials, producing and starring in a sitcom, hosting a variety show and a talk show. Get a copy of Jennifer Keishin Armstrong’s When Women Invented Television here.

Betty White never knew what crazy idea she’d come up with next as she applied powder to the face of her TV co-host, Al Jarvis. Jarvis was “a chunky man of medium height, pushing forty—from one side or the other,” as White later described him. As she tended to his shiny forehead, she had already finished her own preparations, arranging her chin-length dark curls just so and highlighting her flawless ivory skin. That constituted her daily morning routine circa 1949 backstage at a studio in Hollywood, a building on Cahuenga just south of Santa Monica Boulevard that had recently been converted from a radio to a television operation. White, then twenty-seven, served as the makeup department while she and her cohost planned their episode. There was no writers’ room, just makeup time.

That was what Betty White had to offer television: her crazy ideas, her willingness to do whatever it took to succeed, and her outrageously charming personality. Betty and Al’s chats during makeup application were as close as they’d get to rehearsing for the five and a half hours they were about to spend in front of cameras broadcasting live. To be clear, that’s 330 minutes of uninterrupted airtime nearly every day, with no live audience to play off of and no commercial breaks—just pitches for sponsored products that they themselves delivered.

As Betty primped Al, they’d come up with a few loose ideas about how to keep their audience entertained for all of those daytime hours—sketches that would provide a bit of structure to their ad-libbing. They’d wing the rest. This was how they got through six days a week for Hollywood on Television.

On one such day, Jarvis pitched a rough idea for a conversation starter they’d use on the air later: “Let’s talk about how you’re going to take dramatic lessons.” He didn’t have much else to go with for now, but that was standard for them. White knew what to do. Her motto was: Always say yes. Improv came naturally to her.

A few hours later, as cameras rolled, White came up with a fictional drama teacher in response to his prompt. They made up the details as they went. The teacher’s name: Madame Fagel Bagen- hacher, who had, of course, changed her name from Madame Fagel Bagelmaker. (She was, presumably, a Jewish immigrant.) Details continued to emerge over several days of sketches: Madame Bagenhacher lived in an apartment with beaded curtains and would sometimes send White out to fetch her medicine. Once, White explained, Madame Bagenhacher spent a whole lesson teaching how to get into and out of a carriage, because, she said, you never knew when you might be cast in a period movie.

As Betty and Al kept up the ruse over many shows, Madame Bagenhacher even began to get fan mail.

White would eventually rise to Gertrude Berg’s level of sitcom stardom. But she would get there by first competing with Irna Phillips for the daytime audience full of housewives, and she would do it by helping to invent a new form of her own: the talk show.

By the age of twenty-seven, White had followed her acting dreams through various small parts on radio shows to the new frontier of television, where her charming personality was needed as a hostess. She could look into a camera, her eyes sparkling, then flash the warmest of smiles that made viewers watching her on their living room television screens, strewn across the greater Los Angeles area, feel as though they were right there with her, as though they were the only one she cared about. That charisma of hers alchemized into a superpower in 1949 as television came into its own.

Betty White was born on January 17, 1922, in Oak Park, Illinois. About two years later, her parents, Christine Tess and Horace White, moved with infant Betty from the Chicago suburb to Los Angeles. Tess was a stay-at-home mom with dark hair and an easy smile, and Horace, a balding man who had passed his dimples on to Betty, was a lighting company executive. They made a small, loving family: Tess and Horace adored each other, according to Betty, and they doted on their one child. She felt loved but not coddled. Betty had lots of friends, but she considered her parents her best friends.

She grew up in the Los Angeles area, which perhaps helped to spark the show business ambitions that would drive the rest of her life. Young Betty first thought she wanted to be a writer, so she scripted an eighth-grade graduation play at Horace Mann Grammar School in Beverly Hills. She also played the lead. Because her class had studied Japan, the WASPy preteen wrote a Kabuki-style piece in which she played a princess who talks to a nightingale.

She fell in love with the stage right there as she looked out at the audience, all rapt in her performance. As every person in the room paid attention to her and only her, she thought, “Well, isn’t this fun?”

Just four years later, she sang “Spirit Flower”—a melodramatic number about a flower that bloomed on a former love’s grave—at her graduation from Beverly Hills High School. A man who attended the ceremony, an investor in the fledgling technology known as television, saw her performance and offered her a role that would set the course of her life. He asked if she’d like to appear in a signal test he was running in downtown Los Angeles a few months later.

On a February day in 1939, Betty found herself at the six-story Packard Motor Car Company building in downtown Los Angeles. The stylish structure sat at the corner of Hope Street and Olympic Boulevard, the entrance welcoming potential car buyers with the Packard logo in cursive, lit up with neon—one of the first neon signs in the United States. A row of windows allowed passersby to see the gleaming vehicles inside as cars chugged by on the downtown streets.

Los Angeles Packard dealer Earle C. Anthony was a pioneer in broadcasting, having established his own radio station in 1922 to facilitate internal communication between the Hope Street building and his other area dealership. The station, KFI, was Los Angeles’s second, and its reach grew from 2 to 50,000 watts at 640 AM on the radio dial, where it became a public commercial station and remains in operation as of 2020

Now Anthony was again at the forefront of another new medium, his Packard dealership serving as laboratory. A small crowd gathered on the ground floor, buzzing with excitement. They would see a demonstration that movielike images could be transmitted live to audiences from a distance—that is, a few floors away.

Two months before television would be unveiled at the New York World’s Fair, Betty stood in front of one of the first television cameras ever used, set up on the top floor of the Packard building. She was joined by her school’s student body president, Harry Bennett, to perform for the experimental broadcast at the building.

In a makeshift TV studio, Betty and Harry prepared to perform songs from the operetta The Merry Widow in front of the camera. That thrilled Betty because her idol, Jeanette MacDonald, had starred in a movie production of it. Betty had short, dark hair that she wore in curls, and thin, carefully tended eyebrows like all the movie stars had. She was clad in her graduation dress, which she described as “a fluffy white tulle number held up by a sapphire blue velvet ribbon halter.” They had to wear deep tan pancake makeup on their faces and dark brown lipstick “so we wouldn’t wash out,” she later said. The hot lights necessary for the early cameras coaxed sweat from their pores.

Soon their moment came. The camera switched on. They waltzed and sang for the watching lens.

Success: the signal beamed down to a monitor on the first floor of the building, where the audience, including Betty’s and Harry’s parents, stood among the Packard cars and watched the teenagers waltz and sing. This “broadcast” on one of the earliest TV systems had reached its viewers. Betty and Harry had appeared on a television before almost anyone else in the world, albeit on a test channel seen by just a handful of people.

After the experiment, White began to consider what kind of performing career she wanted to pursue. At first, she believed her calling was music. Instead of going to college, she opted for classical voice training. Her instructor, the opera singer Felix Hughes—the film and aircraft tycoon Howard Hughes’s uncle—encouraged her in her hope of becoming an opera singer herself. But as White’s mother, Tess, later wrote, a bout of strep throat that lingered for several weeks devastated Betty’s vocal cords and ruled out a life of divadom. White herself later described it differently: “I had been studying singing diligently, and my mind and heart were set on an operatic career,” she wrote. “Unfortunately, my voice had no such plans. This didn’t deter me one iota: I was sure that if I worked hard enough, I could whip my voice into submission. Wrong.”

As World War II took over Americans’ lives, Betty set her career plans aside to join the American Women’s Voluntary Services, helping to transport military supplies—toothpaste, soap, and candy— to gun emplacements in the hills of Hollywood and Santa Monica. Her uniform was a garrison cap that sat to the side of her head atop her styled curls, a jacket, and a skirt. In the evenings, she attended dances and activity nights at military rec halls with soldiers who were stationed nearby. She met several boys there and continued to write letters to them after they shipped out.

At first she was saving herself for a young man named Paul whose marriage proposal she had accepted before he had left for service overseas in November 1942. They wrote each other every day. But after two years, she sent him a letter that ended things and returned the engagement ring to his mother.

While she volunteered, she met another young man: a P-38 pilot named Dick Barker, whom she married in 1945. But then, to her surprise, she found herself driving back with him to his home state of Ohio to live on a chicken farm. She divorced him after six months and returned to Los Angeles. As she later explained, “Back in those days, you didn’t sleep with a guy until you married him.”

With the war and her brief marriage behind her, she wanted to find her place in show business. She enrolled at the Bliss-Hayden Theatre just outside Beverly Hills. Run by a husband-wife team of film actors, Harry Hayden and Lela Bliss, the school provided practical experience onstage, with a production every four weeks. The $50-per-month tuition earned students the chance to audition for a role and, if they didn’t get one, to work in the stage crew. Betty landed the lead in her first audition, for Philip Barry’s Spring Dance. After eight performances, the school tackled the wartime romantic comedy Dear Ruth. Betty played the lead again; she was on a roll.

During the performances of Dear Ruth, she met another man. Lane Allan worked as a talent agent and had come to scout the show. He was movie-star handsome, with strong eyebrows, a Roman nose, and a sculpted jaw. In fact, he had done some acting and had changed his name from Albert Wootten to Lane Allan for the stage. He had since decided to become an agent for more career stability.

He returned for the closing-night performance. Betty almost blew her line when she saw his face in the front row again. This time, he came backstage and asked her to join him and his friends for an after-show drink. They began dating.

Lane suggested that she pursue a new line of acting work: radio programs. She made audition rounds, and soon developed a job- seeking routine. She went from station to station and sat in offices, even if there was no particular part on offer. She figured the executives would have to give her something if she hung out long enough. But even as the rejections continued, she made the most of her wide-open schedule, going to the beach, horseback riding, swimming, and dating Allan. She maintained a close group of friends who were classmates from Horace Mann. Many of them had grand ambitions like her; they included a future New York stage set de- signer, a film editor, and a newspaper columnist. They discussed their dreams together, though it’s notable that the others were all young men.

Finally, on one of White’s casting visits to the fifth floor of the Taft Building at Hollywood and Vine, a producer of the popular comedy The Great Gildersleeve, Fran Van Hartesveldt, brought her into his office. She couldn’t get a job, he explained, unless she was in the union.

She found the advice helpful but disheartening. She couldn’t get a job unless she was in the union, but she couldn’t get into the union unless she booked a job. Feeling hopeless, she left his office and headed for the elevators with the lunchtime crowd. The wait stretched for minutes and minutes as the busy elevators tried to get everyone off to their lunch hours.

White turned to head for the stairs instead just as an empty elevator finally showed up. She got in, and right before the doors closed, another passenger hopped in with her. It was Van Hartesveldt. They shared a silent ride down together.

As they stepped out on the ground floor, he piped up, “Listen, I know the spot you’re in. It would help you one hell of a lot to get that union card, so here’s what I’ll do. I’ll take a chance and give you one word to say in the commercial on this week’s Gildersleeve. You won’t break even, but it will get you your card. Think you can say ‘Parkay’ without lousing it up?” Her mouth gaped wide open in response. “Come back to our offices after lunch and the girl will send you over to the union,” he said.

White in fact got to say “Parkay” twice: once for the Eastern Time Zone broadcast, and once for the West. She earned $37.50 total. She had to pay $69.00 to join the union. Her father loaned her the money to make up the difference.

She worried that she would screw up her line, saying “parfait” instead of “Parkay,” but she made it through just fine.

She performed several other uncredited, small speaking roles on the program, delivered a Christmas message on the air, and pro- vided a few sound effects. She even sang a song in a questionable “Mexican” accent for an American Airlines ad. (“Why not fly to Meheeco Ceety/You weel like the treep, ee’s so preety” is how she later described it phonetically.) This led to other bit parts on the radio comedy Blondie and the crime drama This Is Your FBI.

She even landed a role in a movie produced by Ansco camera company to show off its new color film. She would have to shoot on location in the High Sierra in eastern California for six weeks. That prompted tense discussions with Allan, who hadn’t quite counted on her career taking off even to that low altitude. They were still only dating, but they spent hours discussing the difficulties of two-career families. That brought White face-to-face with her conviction that career and marriage didn’t go together. “There are some outstanding examples to the contrary,” she later wrote, “so let me clarify by saying I just don’t feel it’s feasible to start them at the same time and still expect to give full attention to both. The fact that I’m compulsive explains a lot.”

And, she had to admit, she wanted a career more than anything. She took the film shoot as an opportunity to break up with Allan. She figured she’d be more likely to stick to the breakup if she wasn’t near him.

In the movie, called The Daring Miss Jones, an actress named Sally Forrest plays a young woman who gets lost in the woods and befriends two orphaned bear cubs. White—her now shoulder-length hair in huge, looped curls—plays Feeney’s best friend back home who worries about her so much she flies a plane in to rescue her.

White did a little bit of everything on the set. She worked as the de facto script girl, tracking shots and continuity. She often wrangled the cubs because their “trainer” was drunk. That became more difficult as the cubs doubled in size over the length of the shoot.

She developed a friendship with Forrest, who soon became a successful film noir actress, appearing in such movies as John Sturges’s Mystery Street and Fritz Lang’s While the City Sleeps. White returned to the safety of home and realized how much she had missed Allan. The feeling turned out to be mutual: a package from him waited for her at home, containing a Carl Ravazza record of “their” song, “I Love You for Sentimental Reasons.” When they reunited, he professed total support for her career ambitions. They married two months later.

Soon after, Allen’s agency, National Concert and Artists Corporation, went out of business and left him without a job. He had to take a position selling furniture at the May Company, and he squeezed in film roles when he could. The couple’s budget shrank so much that they considered it a grand night out if they went to get a 25-cent hot dog and Delaware Punch at a stand on the corner of La Cienega and Beverly called Tail o’ the Pup, which was shaped like a giant hot dog on a bun. Once, White had to collect some empty Coke bottles around the house to return for their 50-cent deposit so she could pay for her dry cleaning and have a decent dress to wear on her casting rounds.

She really needed to get some more reliable work.

White didn’t care whether she did radio, movies, or even television, a market that looked increasingly promising, or at least like one more possibility, by 1949. Gertrude Berg’s The Goldbergs was flourishing as TV’s hottest new thing, and Irna Phillips was still struggling to crack the code for bringing soap operas to the small screen during the daytime hours. Despite the uncertainties, White saw a market just beginning to open up, and she needed to find a job wherever she could get it. And indeed, TV would be the one to embrace White, in contrast to film’s cold repudiation and radio’s shrug.

On one of her casting rounds, a receptionist surprised her by asking if she would like to speak to a producer who was working on a television show. She said yes, of course. As she later explained, there is one rule for show business success: Whatever they ask you, always say yes. When she went in to meet with the producer, Joe Landis, he asked, “Can you sing?”

She said yes again. Besides, she had studied opera. Just because her voice was no longer suitable for Tosca didn’t mean she couldn’t carry a tune on TV. He hired her on the spot, without even asking to hear her sing. He offered no pay. She said yes anyway.

The special starred Dick Haynes, who was locally famous as a KLAC radio disc jockey with a show called Haynes at the Reins. Landis told White to pick two songs, put on a nice dress, and show up Tuesday ready to sing.

White fretted over her one major job: choosing songs. She spoke of nothing else for the next few days. She asked her husband, her parents, her husband’s parents. Finally, consensus emerged: Landis had asked for something bright, and White didn’t want to stretch herself beyond her vocal capabilities. She would sing “Somebody Loves Me” and “I’d Like to Get You on a Slow Boat to China.”

She arrived at the studio at the appointed time, wearing a black taffeta skirt and a white blouse with sequin flowers on one shoulder. That proved to be all wrong: the taffeta skirt rustled in the microphones wherever she went; the white and the sequins wreaked havoc under the intense lighting, reflecting the light and casting spots on her face.

Nonetheless, she got through the performance, buoyed by the support of the bandleader, Roc Hillman, and the generosity of Haynes himself. She appreciated that she could never see the show, since it was live.

Her career began to flourish, at least as much as it could in television’s small market at the time. Haynes recommended her for a new fifteen-minute comedy show on KLAC called Tom, Dick, and Harry that starred three vaudevillians. Barely a sitcom, the series featured three characters who ran a hotel. It had one set: the hotel desk. Every episode opened with Tom, Dick, and Harry singing their names and popping out from behind the desk. Then White would emerge, feather dusting everything in sight.

That lasted only a few weeks before Tom, Dick, and Harry gave up and left television.

But White had become a KLAC favorite, and soon she found herself sitting at the end of a line of three other young women like herself answering phones, a made-for-TV switchboard operation. They were appearing on KLAC’s Grab Your Phone, which featured four “girls” picking up ringing receivers live on the air. The host, Wes Battersea, asked the audience questions, and viewers called in with the answers. White and the other women received those calls. “It must have looked like a tiny telethon,” White wrote in her memoir. “But we weren’t taking pledges—we were giving out five whole dol- lars for each correct response!”

In the clattering chaos, Betty had an idea: Wouldn’t it be so much more fun if, instead of simply relaying the information about her caller to the host, she delivered it with a little flirtatious smile, some extra sweetness in her voice, maybe a flattering aside, maybe a little banter? She had an instinct for the new medium: no one wanted to see regular old phone answering. She couldn’t—nay, shouldn’t—pretend the cameras weren’t there.

The producer loved it. He pulled her aside and told her, “Betty, I must ask you not to mention salary to the others. We are going to pay you twenty dollars a week because you sit on the end and ad-lib with Wes, but they are only getting ten a week.”

She wondered if he had said the same thing to the others. For all she knew someone else got $20 or even more. But she accepted the bump up, and she understood that she was different from the others, maybe even special. It seemed that even the right kind of phone answering could be scintillating on the small, flickering living room screen. At least when Betty White did it.

Soon another DJ with his eyes on a television career wanted to cast White. Al Jarvis, having seen her other performances, rang her at home, at the apartment she shared with her husband in Park La Brea, a sprawling new complex in West Los Angeles. When she picked up the phone, she recognized Jarvis’s voice from the radio. She had listened to him forever. Everyone had: he was Los Angeles’s biggest DJ with his show Make Believe Ballroom. She could not fathom why the man was calling her.

It turned out he was preparing a daily daytime TV show to be called Hollywood on Television. He planned to play records on the air, similar to his radio show. “Would you like to be my Girl Friday?” he asked.

She thought, Gee, another job! Maybe I’ll make another $20! But the job proved much bigger than that. As she told the story, “not only would I be his Girl Friday, but I’d be his Girl Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday as well.” And she would do so for hours and hours: he went on the air five hours a day on radio, so why wouldn’t he do the same on TV?

“I like the way you kid with Wes Battersea, and since we are going to be on the air for five hours every day, I thought that might come in handy,” Jarvis told White. “The job pays fifty dollars a week. What do you say?”

As usual, she said yes.

She couldn’t wait to tell her husband and her parents: she had landed a huge part on television! She would make more than twice as much per week as she had on Grab Your Phone! She would appear on TV every day! Everyone celebrated, though she noticed Lane was the tiniest bit less excited than her parents were on her behalf. He seemed to like the money part, but he focused right away on how much time she’d spend at the studio. “I should have heard the first faint warning bell,” she wrote; “could it be that my taking a job when I could get one was okay, but an actual career for me was not high on his list of long-range plans?”

Startlingly minimal preparation occurred to get Hollywood on Television onto television. A few meetings with some advertising reps, nothing more.

As a start-up operation the show had sparse production resources, and White did a little bit of everything: applying makeup, booking guests, and hauling props around as necessary. Jarvis was a mentor from the start. “All you have to do is respond when I talk to you,” Jarvis said, explaining the job she was taking on. “Just follow where I lead.” She was in heaven. When she looked back on the time she spent there, from ages twenty-seven to thirty-one, she considered it her college, four years packed with fun and learning experiences that would set the tone for the rest of her life.

Jarvis and White shot on a simple set just below the radio tower atop the station’s Hollywood building. White had spent some of her childhood with her parents in a small white house just two blocks north of there. Her father had sold floodlights to KMTR, the radio station that had been in the exact same building before it had switched over to KLAC.

The broadcast started at 12:30 p.m. so Jarvis could do his popular radio show in the morning. This gave White the morning to do chores around the apartment. She could even walk their Pekingese, Bandit—or “Bandy”—who was a wedding present from Allan to White. The complex didn’t allow pets, so she had to sneak the dog out, riding on her arm under a coat, past the security guards who watched over the eighteen high-rise towers. Once they had made it across the street to the park that housed the La Brea Tar Pits, she and Bandy walked freely.

However, she hadn’t been as sneaky as she’d thought: one day, a security guard called out to her, “Mrs. Allan, your tail is wagging.” Indeed, Bandy’s tail was waving hello from beneath her coat. Blessedly, the security guard then went about his business as if he hadn’t seen a thing.

After walking the dog, she headed three miles northeast to the studio and put in her five hours. The show wrapped up by 5:30 p.m., which gave her enough time to get home and start dinner for Allan. It all seemed as though it would work out, with minimal disruption to her marriage.

Hollywood on Television premiered in November 1949, right around Allan and White’s second wedding anniversary.

Recordings of the show don’t exist, but accounts of its production indicate that it evolved before viewers’ eyes. At first, Hollywood on Television—known as H.O.T. behind the scenes—simply transferred Jarvis’s radio show to the screen. He sat behind a small desk, with White on one side of him and his record player on the other. He opened each show with a brief welcome to the audience, then introduced White, then played a record. Between each song they chatted briefly to the camera.

While the songs played, the audience heard only the music, but they saw Jarvis and White hanging out on the set and talking to each other, their microphones off. Occasionally, the lone cameraman panned to the tank filled with tropical fish, the set’s one distinctive feature, for some visual variety.

Viewers did not care for any of that. By the second week, complaints began to roll in, and what they hated most was that Al and Betty talked to each other and said things that the viewers couldn’t hear. It drove the audience crazy not to know what Al and Betty were saying. So it was decided that Al and Betty would talk for five hours on the air and say whatever they wanted. The turntable was gone, though the fish stayed.

Jarvis and White developed an on-air bit about her being his “Girl Friday”—and Monday, and Tuesday, and Wednesday, and so on. Jarvis often referred to her on the air by the day of the week. As an inside joke, White’s mother bought her pairs of silk panties embroidered with the names of each day. White dutifully wore the proper panties throughout the week.

Three weeks into their run, on Thanksgiving Day, they broad- cast as usual, despite the holiday. After they signed off, Jarvis called White into his office. She recognized the situation: after three glorious weeks, the fun was probably over. Their show must be ending, as all of her shows so far had done.

She entered his office already dejected and was struck by how official Jarvis looked behind that desk. He made things worse when he opened with an apology. This is it, she thought. Then he finished: He was sorry, he said, for keeping her from the holiday with her family. But he wanted to tell her that the station’s manager, Don Fedderson, loved the work they were doing. KLAC would soon launch a big promotion to get the word out about Hollywood on Television to even more viewers. And the station wanted to add a half hour to each day’s airtime, plus an entire five and a half hours on Saturdays.

Granted, only one other station broadcast in Los Angeles at the time, so viewers didn’t have a lot of choices. But viewers did choose Hollywood on Television more often than not. Al and Betty would now ad-lib for a total of thirty-three hours per week. White got a raise, from $50 to $300 per week. She could not believe her good fortune.

Jarvis laughed. Meeting adjourned, happy Thanksgiving.

Viewership grew by the day, driven in large part by the growth of television. The station office expanded. Construction began on a new Hollywood on Television studio on the other side of the lot.

Meanwhile, the station threw a tentlike roof over the building’s patio and drained the fish pond that sat in the middle. Hollywood on Television broadcast from here for the next few months until the new set was finished.

They were on the air. Always. White loved it. She never felt tired out by her exhausting schedule. “For whatever reason, be it workaholism, lack of good sense, emulating a father who loved working above all else, the truth of the matter is, it was plain, flat-out interesting,” White wrote.

They came up with sketch ideas such as Madame Fagel Bagenhacher to entertain their expanding audience. The parade of guests further helped to fill time and inject some celebrity glamour into the show, not to mention spectacle and fresh excitement: the audience could now see their favorite singers and musicians instead of just hearing them, and they could discover new favorites as well. The jazz musician Herb Jeffries, known for his appearances in Western musical films for Black audiences, appeared before the cross section of KLAC’s daytime viewership. The French singer-actor Robert Clary, who had survived a concentration camp by performing for SS soldiers, appeared on the show early in his American career, singing songs in French. Billy Eckstine and Nat King Cole were also among the guests.

The blond singer Peggy Lee stopped by to do a number. When White returned home that night, she found her father was smitten. “That girl in the green suit,” he said. “She’s really something.”

The on-air proceedings had a frontierlike atmosphere in which anything could happen. Anxiety could erupt into laughter. Impending disaster could lead to high comedy. Jarvis and White had to appease their sponsors and keep KLAC’s entire daytime schedule afloat, so the stakes were high, but no one was sure how to measure the quality of their work or their success. They didn’t aim for a seamless show. They just worked to keep viewers interested. And, of course, to keep the commercial spots flowing.

Sometimes those two goals conflicted, particularly when Jarvis’s friend Buster Keaton stopped by for occasional appearances. Keaton, a genius of the silent film era, combined physical comedy and deadpan expression to brilliant effect. (The critic Roger Ebert would later call him “the greatest actor-director in the history of the movies.”) Keaton, too, had a syndicated half-hour show in 1950.

Once, as he and Jarvis schmoozed and bantered and schmoozed some more on camera, the required commercial spots, to be delivered by White, continued to stack up. The men seemed oblivious. White grew nervous. After all, the show existed through the beneficence of Thrifty Drugstore. Commercials were the real point of the program; the “entertainment” portions were incidental. “As our audience multiplied, our commercial load increased proportionately, and if an interview ran a little long or Al happened to get carried away on a subject, or if we began having a little too much fun, we knew we would have to pay for it,” White wrote. “Once we slipped behind, we’d face having to do three or four spots in a row to catch up.”

Finally, time had run out, even as Jarvis and Keaton prattled on. White cut in with her pitch for Thrifty, displaying the products available at the store. Keaton, sensing a comedic opportunity, wandered into the spot.

First he watched from the sideline. Then he went in. As White spoke about toothbrushes, he picked one up and pantomimed brushing his teeth. With each product, he followed her, miming with the drugstore items one by one.

Committed to professionalism, White breezed on, touting the wonders of each product and allowing Keaton’s comedic genius to take its course. She knew she was the straight woman to his deadpan physical bit. For ten minutes, Hollywood on Television became high art. Luckily the Thrifty executives loved every minute.

White delivered many of the ads on the show, and there could be nearly sixty in a given five-and-a-half-hour episode. (The longer format of the show required multiple sponsors, unlike shows that were sixty minutes or shorter.) Adding to the challenge, both she and Jarvis refused to read off a script on camera or even use cue cards. They memorized what they needed to know about the products and delivered as best they could while broadcasting.

That didn’t always turn out well. One time, White glanced at some new ad copy and headed to her spot on camera to tell viewers about a handy attachment for the kitchen sink. “You put the soap in here, then press this little button, and—and soapy water comes out of your—of your—” She could not remember the word for “faucet.” She attempted to finish things off anyway: “ and soapy water comes out of your gizmo.” Jarvis and cameraman Bill Niebling cried and shook with laughter—the shaking a much bigger problem for Niebling, who was holding the camera. Soon White convulsed with laughter as well.

Sometimes, as the show developed, hired pitchmen performed the ads. Many of the spots resembled a visit from a traveling salesman: the pitchman would toss dirt across the studio floor and demonstrate how well his vacuum cleaner sucked it up or tote in a sewing machine and offer it to the audience for the low price of $19.95. Lou Slicer came by to show off his kitchen gadget, which also, as the station learned from irritated letters, sliced many viewers’ fingers. Charlie Stahl brought his sofas and jumped on them to demonstrate their resilience. White herself often couldn’t resist the pitches delivered on the show: she purchased an O’Keefe & Merritt gas range as well as press-on manicured nails that took the top layer of her own nails off with them.

Animals emerged as another favored way to fill airtime. Betty loved animals, especially dogs, and had grown up in a pet-loving home. One episode of Hollywood on Television featured a Saint Bernard and her two-month-old puppy, who arrived on camera with a can of Dr. Ross Dog Food (sponsored!) tied under his chin with a red bow. White held the puppy up, did her signature look straight into the camera, and addressed one particular audience member who she knew for a fact was watching on her new ten-inch Hoff- man set: “Mom?” Betty pleaded. Her mother kept the set on channel 13 for all five and a half hours every day. Stormy was the family pet for the next eleven years.

Almost anything could turn into a segment for the show, given the hours to fill. One time, White dressed as a young girl, sat on huge furniture, and sang “Young at Heart.” Other times, she and Jarvis riffed on local news stories, even violent crimes, or discussed their ideas (mainly, Jarvis’s ideas) about local politics. Those segments often elicited floods of viewer mail. One of Jarvis’s particularly popular rants called for stricter penalties for sex offenders. Still other times, Jarvis opened a wooden gate on the set that led right out onto Cahuenga Boulevard. If someone passed by, he’d call them in to be interviewed on camera.

White and Jarvis added to their cast of regulars, which helped them to fill their allotted hours. Mary Sampley dressed in a kelly green uniform to deliver local car race results, sponsored by Kelly Kar Kompany. KLAC sports director Sam Balter offered updates from the world of athletics. Piano player Ronnie Kemper provided music. Station manager Don Fedderson’s friend, a Unity Society minister named Dr. Ernest Wilson, closed out the show with a Thought for the Day. He told White he “loved doing the show be- cause it was the only way he knew to be heard in every bar in town.” White realized that even the local fame she enjoyed could have gotten the better of her. But Jarvis was a good teacher, role model, and grounding force. He had rules to deal with audiences: “Never to talk down to them—nor, for that matter, over their heads. Without ever claiming such was the case, to give the viewers the comfortable feeling that you could have come to work on the bus.”

Alas, the success White had so long hoped for took a toll on her marriage. A little more than two years after their wedding, during Hollywood on Television’s first year, Betty and Lane separated. He ad- mitted that he didn’t want a wife with a career as big as White’s had become. She described him as “all the good things I thought I had seen,” but she couldn’t abandon her ambition. She resolved never to marry again. She realized she was a career girl at heart. “I love working,” she later said in an interview with her friend Jane Ardmore, a journalist. “It’s part of me. So I love my freedom and this is how it’s going to be. Forever.” She remained friendly with Allan and attributed the marital breakdown to having made the wrong match at the wrong time. At age twenty-eight, she had now divorced twice, but she was on her way to the kind of career she could love. Unlike Allan, White’s parents supported her aspirations. She moved back in with them in their house in Brentwood. They celebrated with her any time she came home and announced a career victory.

Around this time, the average age of marriage for women was twenty-eight, and birth rates doubled in the postwar flush of economic stability. Middle-class white women such as Betty White were expected to get married, stay married, and remain happily at in their husbands’ homes to raise children and tend to domestic du- ties. In fact, such a life was seen as idyllic: with so many new gadgets to make housework easier than ever, including washer-dryers and electric mixers, they had it good! Why wouldn’t they want to give up working outside the home to enjoy the cozy satisfactions of unpaid home labor?

White, however, saw her life differently; she would devote her- self to her work for the foreseeable future. Lucky for her, television’s power was growing every day.

Local Los Angeles television had proven that power in 1949 with a real-life tragedy. A three-year-old girl named Kathy Fiscus fell into a well in the Los Angeles suburb of San Marino on the afternoon of April 8, and the rescue effort was broadcast live on KLAC’s main competitor, KTLA. Crews with drills, bulldozers, and trucks from surrounding towns, aided by Hollywood studios’ floodlights, convened to save her. By the time they got to her on the evening of April 10, she was dead. At that point, twenty-five thousand people, beckoned by the news coverage, had gathered on the site. Thou- sands more watched at home on television. Her headstone reads, “one little girl who united the world for a moment.”

The reach of television on Hollywood’s home turf was undeniable. But that didn’t mean anyone knew how to make a cohesive, professional daily entertainment broadcast. White, Jarvis, and KLAC did their best to figure out what daytime television might look like, with no references to guide them. The same was happening at KTLA. Monty Margetts, an actress and radio announcer, became one of the station’s biggest stars by hosting the city’s first televised cooking show, Cook’s Corner. The subversive twist: she didn’t know how to cook. Viewers delighted in writing in to give her pointers.

As White, Jarvis, and Margetts bluffed their way through their first year on the air, television had come a long way since the first commercial TV networks began in 1941 in New York City, but it had a long way to go before it would overtake radio as the nation’s main form of mass communication. At this point, it was a relative rarity that appeared mostly in the homes of the wealthy. The first TV owners on any given block would find themselves suddenly very popular, their home a gathering spot for folks eager to catch a glimpse of Milton Berle or William Boyd, who played Hopalong Cassidy.

Critics differed as to what television might become. Around 1950, the media scholar Charles A. Siepmann predicted that TV would “conform rapidly to a few stereotyped conventions. It will be technically ingenious and inventive but artistically poor. Except on rare occasions, and for some time to come, its true scope as a medium of expression will not be fully realized.” But the critic Gilbert Seldes, one of the first to take TV seriously, said, “The extraordinary sense of actuality given off by live television programs can show up the fictitious quality of the movies, the artifice which has become their art.”

In any case, movies had no reason to fear television yet. Most of the TV schedule consisted of variety shows, which were easy to produce live because of their loose and unscripted structure, and daytime talk shows such as Hollywood on Television, which were equally uncomplicated. East Coast production was developing rap- idly, but the West Coast had Betty White, Monty Margetts, and little else. Further hampering the medium’s progress, the Federal Communications Commission in fall 1948 froze new station applications while the government agency figured out how to proceed with licensing. It had allowed several stations to cluster too close together, causing interference. Too much was happening too fast. That meant that the western half of the country, in particular, remained isolated from the East Coast stations, which were being connected by a growing cable network that allowed them to receive New York’s live broadcasts. East Coast shows made it to White’s side of the country only via inferior kinescope recordings, days or weeks after they had aired. And shows that originated on the West Coast mostly stayed on the West Coast, forced to be content with only regional success.

Still, the TV industry was inching toward viability. As TV sets proliferated, broadcasters diversified their offerings, including children’s programming such as Howdy Doody and dramas such as The Lone Ranger, sitcoms such as Gertrude Berg’s The Goldbergs, and Irna Phillips’s daytime soap These Are My Children. As of 1949, the TV business remained welcoming to such women. From the late 1940s on, women’s trajectory in television would be one of revolution followed by retrenchment, several times over. Each of these women would experience inevitable setbacks but would move us farther forward than back.

The first revolution was just getting started, and one more true revolutionary was about to join: the glamorous jazz superstar Hazel Scott would soon become the first Black person to host a primetime network television show.

Get your copy of Jennifer Keishin Armstrong’s When Women Invented Television here.