We’re proud to present an excerpt from a new book written by Robert K. Elder, Aaron Vetch and Mark Cirino, “Hidden Hemingway: Inside the Ernest Hemingway Archives of Oak Park“. The passage below explores Hemingway’s experiences with Hollywood.

Synopsis of the book (from Amazon.com): Thinking of Ernest Hemingway often brings to mind his travels around the world, documenting war and engaging in thrilling adventures. However, fully understanding this outsized international author means returning to his place of birth. “Hidden Hemingway” presents highlights from the extraordinary collection of the Ernest Hemingway Foundation of Oak Park.

Thoroughly researched, and illustrated with more than 300 color images, this impressive volume includes never-before-published photos; letters between Hemingway and Agnes Von Kurowsky, his World War I love; bullfighting memorabilia; high school assignments; adolescent diaries; Hemingway’s earliest published work, such as the “Class Prophecy” that appeared in his high school yearbook; and even a dental X-ray. “Hidden Hemingway” also includes one of the final letters Hemingway wrote, as he was undergoing electroshock treatment at the Mayo Clinic. These documents, photographs, and ephemera trace the trajectory of the life of an American literary legend.

The items showcased in “Hidden Hemingway” are more than stagedressing for a literary life, more than marginalia. They provide definition—and, in some cases, documentation—of Hemingway’s ambition, heartbreak, literary triumphs and trials, and joys and tragedies. It’s Hemingway’s stature as a Pulitzer Prize– and Nobel Prize–winning author that draws so many biographers and historians to his work. It is also the wealth of material he left behind that makes him such a compelling, engaging, and often polarizing figure.

For Hemingway, the material he saved was both autobiography and research. He gathered data and details that made the life lived in his books more authentic. The authors of “Hidden Hemingway” have done the same, telling a life story through items that illuminate Hemingway’s legacy. Some of the material contradicts the public image that Hemingway built for himself, and some supports his larger-than-life myth. In all, “Hidden Hemingway” celebrates the Ernest Hemingway archives and Oak Park’s most famous author.

Hemingway’s Tortured Relationship with Hollywood: An Excerpt

Ernest Hemingway avoided Hollywood, where many of his literary peers—notably William Faulkner and F. Scott Fitzgerald—were lured by easy money to write scripts. He felt that novelists who turned to screenwriting had to write “as though you were looking through a camera lens. All you think about is pictures, when you ought to be thinking about people.” Hemingway’s philosophy about Hollywood was to “throw them your book, they throw you the money, then you jump into your car and drive like hell back the way you came.”

It’s not a surprise then, that Hemingway was rarely satisfied by the treatment of his work in the movies: “Except for the film versions of ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls,’ ably acted by his good friends Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman, and his friend Spencer Tracy’s creation of the role of Santiago in ‘The Old Man and the Sea,’ Hemingway could hardly endure to sit through the cinematic or televised versions of any of his works,” wrote biographer Carlos Baker.

Adapting Hemingway to the screen was no easy feat. Screenwriter Ben Hecht (“Scarface,” “Notorious”) lamented over—or complained about—the simplistic grace of Hemingway’s prose, and how difficult it was to translate on screen. “The son-of-a-bitch writes on water,” he complained. Aldous Huxley similarly said of Hemingway’s prose, “Hemingway’s gift is that he writes in the white spaces between the lines.”

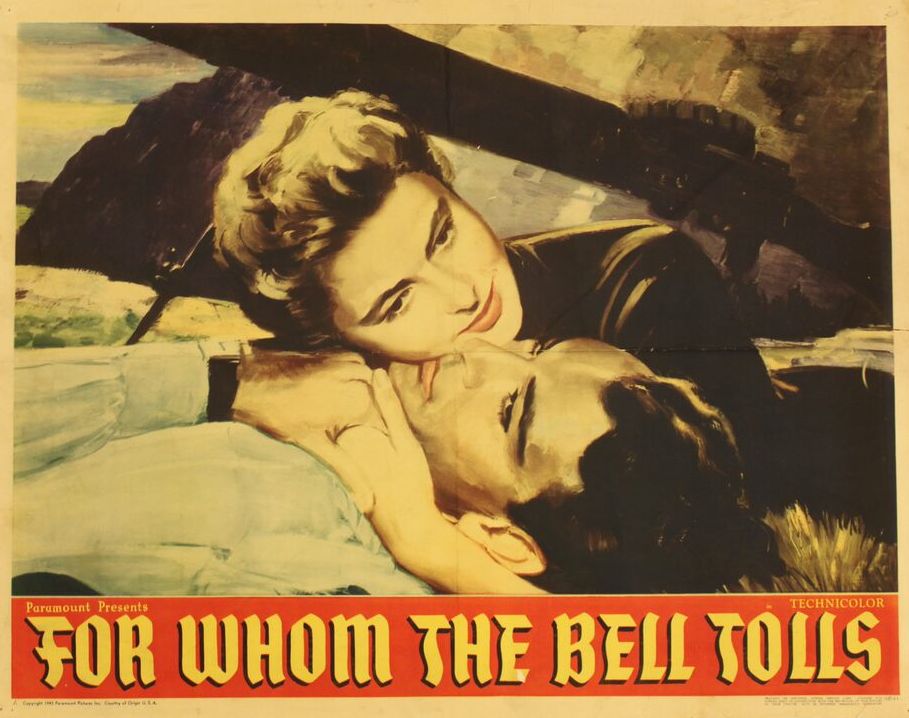

Paramount bought the film rights for “For Whom the Bell Tolls” for nearly $150,000 three days after the publication of the book. The studio initially considered Cecil B. DeMille to direct the project but finally chose Sam Wood (“The Pride of the Yankees,” “Our Town”). Posters for the release of the 1943 film of “For Whom the Bell Tolls” emphasize the stars playing the leads, Ingrid Bergman and Gary Cooper. An on-location shoot in California’s High Sierra Mountains proved challenging. “I never experienced anything as difficult as filming under the conditions we had, at an elevation of 10,000 feet, scrambling over rocks,” Wood remembered.

After a critical drubbing over its running time, Wood ended up carving thirty minutes out of the film for a second run. Yet the movie was still nominated for nine Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Although Bergman and Cooper were nominated in the Best Actress and Best Actor categories, respectively, only Katina Paxinou won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her role as Pilar. Cooper was complimented on his work by Hemingway, according to the former’s biographer, Stuart Kaminsky. “You play Robert Jordan just the way I saw him, tough and determined. Thank you,” Hemingway told Cooper.

Cooper became friends with Hemingway and visited the author at his home near Sun Valley, Idaho, where they hunted together. According to film scholar Gene D. Phillips, “neither ever mentioned to the other the 1932 “A Farewell to Arms” in which Cooper had starred and against which Hemingway still harbored a grudge.”

(The grudge stemmed not from Cooper’s performance, but from the film’s multiple endings and Hemingway’s financial compensation. Hemingway’s issues began with playwright Laurence Stallings, who had adapted a 1930 stage version of the novel, which had an undistinguished run on Broadway. Hemingway was unhappy that the film version would adapt Stallings’s play rather than his novel. Stallings got $24,000 for the screen rights to his play, the same fee Hemingway received for the screen rights to the novel itself. Famously, the film was offered to distributors with two different endings, one in which Catherine Barkley, played by Helen Hayes, dies and another in which the love stricken nurse appears to survive, just as bells ring in the Armistice.)

Both Cooper and Hemingway had both championed Ingrid Bergman to play Maria in “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” Hemingway and his third wife, Martha, met Bergman and her husband in San Francisco for lunch as the film was being cast. Afterward, he gave her a copy of the book, inscribed “To Ingrid Bergman, who is the Maria of this book.” Bergman started on “For Whom the Bell Tolls” the day after she finished “Casablanca.” Hemingway cultivated a friendship with Bergman, even sending her advice when she was being pilloried for her affair with director Roberto Rossellini (whom Hemingway referred to as “the 22 pound rat”).

Still, he wrote: “Great actresses always have great troubles sooner or later… All things great actresses do are forgiven…Everybody reaches wrong decisions. But many times the wrong decision is the right decision wrongly made.” Hemingway rarely felt as forgiving toward the adaptations of his work.

Excerpt from “Hidden Hemingway: Inside the Ernest Hemingway Archives of Oak Park“ by Robert K. Elder, Aaron Vetch and Mark Cirino (Kent State University Press, June 27). Reprinted by permission of the publisher; all rights reserved.

For more information, visit HiddenHemingway.com or follow @HiddenHemingway on Twitter.