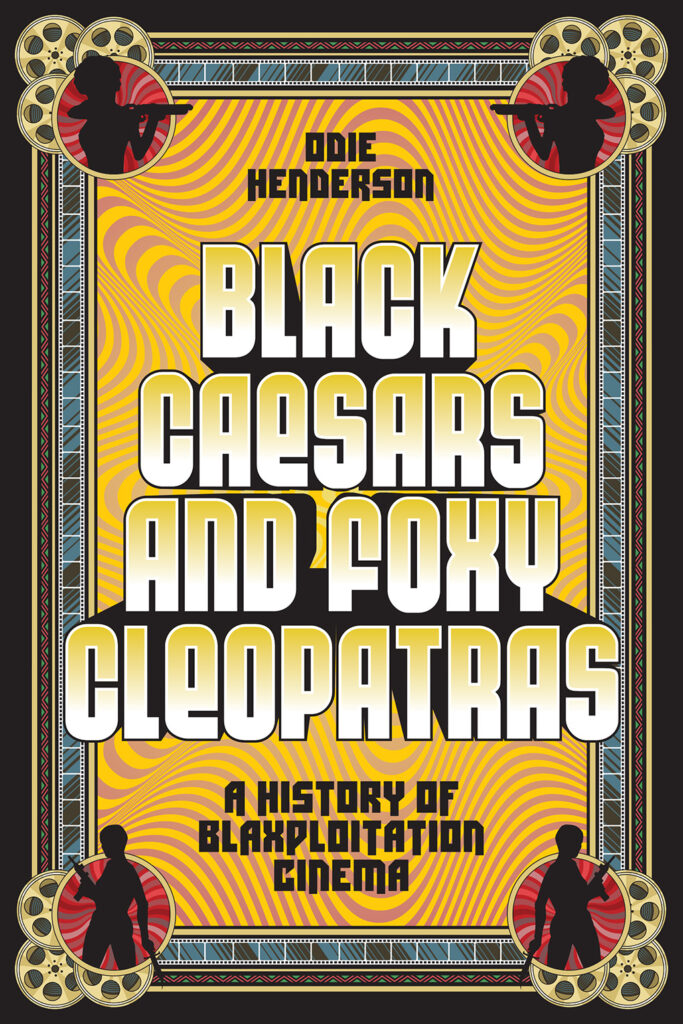

We are incredibly proud to present an excerpt from Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras: A History of Blaxploitation Cinema by Odie Henderson. Get your copy here. And please join us for a special conversation between Henderson and Managing Editor Brian Tallerico at the Music Box Theatre on February 27th.

Here is the official synopsis, followed by the excerpt:

A definitive account of Blaxploitation cinema—the freewheeling, often shameless, and wildly influential genre—from a distinctive voice in film history and criticism

In 1971, two films grabbed the movie business, shook it up, and launched a genre that would help define the decade. Melvin Van Peebles’s Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, an independently produced film about a male sex worker who beats up cops and gets away, and Gordon Parks’s Shaft, a studio-financed film with a killer soundtrack, were huge hits, making millions of dollars. Sweetback upended cultural expectations by having its Black rebel win in the end, and Shaft saved MGM from bankruptcy. Not for the last time did Hollywood discover that Black people went to movies too. The Blaxploitation era was born.

Written by film critic Odie Henderson, Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras is a spirited history of a genre and the movies that he grew up watching, which he loves without irony (but with plenty of self-awareness and humor). Blaxploitation was a major trend, but it was never simple. The films mixed self-empowerment with exploitation, base stereotypes with essential representation that spoke to the lives and fantasies of Black viewers. The time is right for a reappraisal, understanding these films in the context of the time, and exploring their lasting influence.

Every genre has its Citizen Kane, that is, the greatest movie in its canon. Super Fly fits that bill for Blaxploitation. Its screenplay, by Phillip Fenty, is tightly constructed, with hustler characters breathing life into the “one final score” trope commonly found in heist movies. It is very well-acted with few exceptions. The reviews were better than most of the films that preceded and succeeded it. The soundtrack became a best-selling classic soul album. And its fashion sense, inspired by Nate Adams’s costume choices and the actors’ own closets, started a trend so widespread that it influenced this book’s author’s mother, who dressed him in a rust-colored “Super Fly coat and hat” ensemble when he was three years old. He looked fabulous.

One of the characteristics that makes Super Fly a valid contender for the top of the Blaxploitation heap is its shocking amorality. Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song had a similar viewpoint, but its hero eventually realized that the community took precedence over his individual needs. Super Fly posits the exact opposite: Youngblood Priest’s (Ron O’Neal) actions are done solely for self, with no regard for his fellow man. Gordon Parks Jr.’s film forces the viewer into making a potentially fraught decision about its protagonist. Rooting for him is an act of capitalistic complicity; rooting against him is siding with the corrupt system that made his hustle necessary. “A victim of ghetto demand” is how the film’s title song puts it.

Either way, Priest is an antihero whose lifestyle appears seductive even in its most unpleasant moments. He’s a gorgeous-looking light-skinned Black man with a straight hairdo to die for and threads that fit the title (Super Fly is two words, not one; an adjective, not a noun). He sleeps with the “baddest bitches in the bed,” as Curtis Mayfield sings in his brief cameo. He also drives an incredible car and has $300,000 in a safe, all of it made by his team of cocaine dealers. Violating the cardinal rule of drug dealing, Priest partakes in his product, usually via a coke spoon dangling from his necklace. He snorts so much cocaine that the viewer wonders how he can stay upright, let alone unleash karate ass whippings on his enemies. The plot hinges on whether he can turn that $300,000 into a cool million bucks by saturating Harlem with enough coke to make Scarface’s Tony Montana look amateurish.

Helping him achieve this goal are his right-hand man, Eddie (Carl Lee), his mentor Scatter (Julius Harris), and Fat Freddie (Charles McGregor), a hapless low-level clocker who meets a tragic end. Giving Priest trouble are assorted Harlem competitors, corrupt politicians, and crooked White cops, one of whom is played by the film’s producer, Sig Shore. Providing a small peek into the other major racket in Harlem is a pimp named K.C. The scene with K.C. is completely extraneous, very poorly acted (it’s impossible to understand his dialogue), and feels as if it were some kind of mandatory condition hoisted on the filmmakers. Actually, it was—the real-life pimp allowed the use of his customized Caddy in exchange for an onscreen appearance and an “Introducing” mention in the opening credits.

Keeping Priest sexually satisfied are his two main squeezes, one Black (Sheila Frazier, in her film debut) and one White. Priest is introduced in a postcoital scene with the latter, Cynthia (Polly Niles). When she begs him not to go, he offers her a sniff of his product as a trade-off for his having to leave. She turns him down, saying, “Some things go better with coke.” That was Coca-Cola’s slogan at the time, so this was a product placement the Atlanta based company probably didn’t appreciate.

Frazier’s Georgia has more scenes and a more fleshed-out characterization, but she’s still reduced to being a booty call for the hero. When she auditioned for the role, the producer, Sig Shore, didn’t want her. According to Frazier, he desired a more buxom actress. Aggravated by the runaround she received during the auditions, she gave up, changed her phone number, and moved to a different apartment in New York City. While doing this, Shore had a change of heart, but no one could find her. By sheer coincidence, she ran into someone associated with the production who recognized her. Frazier learned that the filmmakers were frantically searching for her.

To one-up Shaft’s shower sex scene, Georgia and Priest get it on in a bubble bath, screwing in slow motion as the audience tries to figure out the logistics of the tub and their bodies. (“I had no idea they were going to shoot it that way!” Frazier said.) More than one review cited this scene, and it surely inspired some folks to discover that bathtub sex isn’t as easy as this movie makes it out to be. Especially without the benefit of slow-motion in real life.

Ron O’Neal may be the main character in Super Fly, but he’s not the true star of the movie. That role went to its score by Curtis Mayfield. Mayfield appears onscreen in the requisite Blaxploitation movie club scene, but his compositions rule the soundtrack so much that Super Fly often feels like a music video. Shaft may have received the Oscar nomination for Best Score, but Super Fly has the better application of its music. And while Shaft deservedly won the Oscar for its hero’s unforgettable theme song, Super Fly ups the ante by giving its hero two unforgettable themes, “Pusherman” and “Superfly.”

Super Fly’s soundtrack, released two months before the film, in June 1972, also sold more copies than the Shaft double album in its original release. In fact, Super Fly the album made more money than Super Fly the movie, paving the way for song-filled soundtracks like 1977’s equally successful Saturday Night Fever. The album’s first single, “Freddie’s Dead,” was released in July and reached number 4 on Billboard’s Hot 100 and number 2 on its R&B chart.

Mayfield’s music is in constant conversation with Super Fly, underscoring what’s onscreen but also occasionally offering up a contrapuntal narration. An example of the former is the opening scene. Two junkies who will later try to rob Priest are shown running the streets of Harlem, angrily discussing their plans. “Little child, running wild,” sings Mayfield on the soundtrack, describing the men from his omniscient perch in the theater speakers. He knows what they’re up to before the viewer does, and it lends the scene a suspenseful aura. And his soothing, sexy falsetto on “Give Me Your Love (Love Song)” makes the aforementioned tub sex scene even steamier.

Based on his twelve years writing songs for his gospel/soul music group, the Impressions, Super Fly might have seemed a bit of a stretch for Curtis Mayfield, in terms of subject matter and language. But his music had already taken a rawer, more sociopolitical turn on his 1970 debut solo album, Curtis. Its leadoff song, “(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Below, We’re All Going to Go,” opens with a vocally distorted Mayfield yelling “n*ggers,” “crackas,” and “whiteys” before condemning everybody to hell.

Additionally, this was a man born into the Chicago ghetto on June 3, 1942, so the salacious material was not going to be foreign to him. “Street living gives you something special,” he said of his upbringing. “You don’t have to turn out bad. You can learn the rights and wrongs in the street, and sometimes I think the education you get in the streets is more valuable than what you get in school.”

The Chicago native who knew the seductive allure of a ghetto hustle is in musical residence, but so is his alter ego, the activist who wrote all those Impressions songs. Long before Super Fly would be lambasted for its depiction of drug use, Mayfield pointed out that it played like “a commercial for cocaine” and chose to counter that notion. As a result, there’s a tension between what is heard and what is seen. It’s explicit in songs like “Eddie You Should Know Better” and “No Thing on Me (Cocaine Song),” and it’s implicit in “Freddie’s Dead,” a song whose lyrics are not heard in the film (costing it Best Song Oscar eligibility), but were well-known by audiences when Super Fly opened. A lament for Fat Freddie, who gets killed in a hit-and-run, the song also serves as a warning for anyone who decides to pursue Freddie’s lifestyle: “If you wanna be a junkie, wow! Remember Freddie’s dead.”

Speaking of commercials for cocaine, Super Fly’s most controversial sequence is exactly that. Like his father, who directed Shaft, Gordon Parks Jr. was a shutterbug of some note. He used his skills to take pictures of numerous people enjoying Priest’s product. These stills propel the narrative of Priest’s final big score forward and are edited with Madison Avenue–level precision into a montage depicting cocaine-fueled euphoria. In an interview, the comedian Sinbad said a lot of his friends saw this sequence and became convinced selling drugs was for them.

Though this montage is Super Fly’s biggest flex of amorality, it still had to contend with Mayfield’s voice on the soundtrack. “Pusherman,” the most complicated track on the score, is reprised here. On the surface, it’s a boastful Blaxploitation hero’s song, but underneath its braggadocio is a message to drug users: the dealer owns your soul and he’ll use your destruction to fuel his success. “I’m your mama, I’m your daddy, I’m that n*gger in the alley,” Mayfield sings in his sexy, seductive, and ultimately Satanic falsetto. This is a deal with the devil that won’t work out for the junkie. The song is hypnotic, with its relentless percussion distracting from the brutal bluntness of its words. Whether this successfully counters the visual intent of all those happy cokeheads is debatable, but it does at least muddy the waters.

When Deputy Commissioner Sig Shore finally catches up to Priest during the climax, he demands not only a big cut of the profits from this big score but also Priest’s continued employment. Priest has outsmarted him, however, by purchasing a Mafia hit on the commissioner in the prior scene. Should anything happen to him, the commissioner gets rubbed out by “the best killers, WHITE ONES!”

“You better take real good care of me,” Priest warns. “Nothing, nothing better happen to one hair on my gorgeous head. Can you dig it?”

Like Sweet Sweetback, Youngblood Priest gets away with it at the end. And, like Van Peebles’s runaway success, Super Fly made a lot of money, 90 percent of it from Black audiences in Black neighborhoods. It successfully fended off Shaft’s Big Score!, the sequel to Shaft that was once again directed by Gordon Parks Sr. and scripted by Ernest Tidyman. Viewers who had already seen that film when it opened in June flocked to Super Fly. In one week, it made $65,000 in Baltimore, $43,000 in St. Louis, $40,000 in Kansas City, and $30,000 in D.C. In the last week of August 1972, it outgrossed The Godfather, a movie that was constantly being compared to Super Fly in numerous articles. The comparison was based not on box office but on outrage. Italian-American groups were livid with Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo’s depiction of them, and Black organizations like the NAACP and CORE were equally angry about Super Fly.

In a joint statement, the two organizations proclaimed:

“The movie epitomizes, without any hint of retribution, the absolute worst images of blacks. Super Fly glorifies the use of cocaine, casts doubt upon the capability of law enforcement officials, casts blacks in roles which glorify dope pushers, pimps and grand theft.”

The two groups were adamant about banning this new genre of film, an action that ran counter to the average moviegoer’s opinion on the matter. If all the pushback over Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song did little to stem the tide of Blaxploitation, why would the same arguments be effective against a far less avant-garde and more polished product like Super Fly? As more films of this ilk began to be released, the sense of outrage grew. In October 1972, the Coalition Against Blaxploitation was formed. Like the Catholic Legion of Decency that policed Old Hollywood, this coalition would issue ratings to describe Black movies as “Superior, Good, Acceptable, Objectionable, or Thoroughly Objectionable.”

‘Excerpt from the new book Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras: A History of Blaxpoitation Cinema by Odie Henderson published by Abrams Press ©2024’