The English-speaking world of cinephilia is in shock today at the passing of Philip Seymour Hoffman. No; any fan of the art, English-speaking or otherwise, is in shock today. Hoffman was a monumental talent, an actor capable of evoking the most complex of feelings through the twitch of an eye. When I watched him live on Broadway in “Death of a Salesman”, I didn’t see a 44-year old actor, but a sad, disillusioned and bitter old man. It proved Hoffman didn’t need heavy makeup or the artifices of cinema to completely transform himself. When his talent was put together with editing, cinematography and the other cinematic techniques, the results were often staggering. Watch him in “Synecdoche, New York” and witness the fruition of everything cinema has to offer us.

However, if you’re from a Portuguese or Spanish-speaking country and are familiar with Latin documentarians, this Sunday was an even bigger tragedy: we also lost Eduardo Coutinho, who is arguably one of the most sensitive and brilliant filmmakers cinema ever had.

A few months ago, Coutinho was finally invited to became part of the Academy after decades of prolific and frequently revealing work.

Now he’s dead at 80.

Stabbed by his own schizophrenic son, who also tried to kill Coutinho’s 62-year-old wife and himself (they are in surgery as of this writing).

When I heard the news, my heart broke. First, Roger Ebert; now Eduardo Coutinho. My heroes are going fast.

Yes, hero. Coutinho was not only a fantastic filmmaker; he was a revolutionary. He changed by himself the face of documentaries in Brazil and, dare I say, throughout the world. There’s not one Brazilian documentary filmmaker under 60 who was not heavily influenced by Coutinho’s work.

I certainly was.

My favorite Brazilian movie is “Cabra Marcado para Morrer” (“Twenty Years Later”), which has a fascinating story itself: It started in 1964 as a project in which Coutinho was going to tell how a peasant leader, João Pedro Teixeira, was killed by landowners two years prior. To make things more authentic, he decided to cast the man’s widow as herself, and other poor farmers in the other roles. That’s when the military coup happened in Brazil. The police arrested part of the movie’s crew and tried to confiscate their footage. Coutinho managed to retrieve what he had filmed, and escaped.

Seventeen years later (yes: 17), Coutinho looked for Elisabeth Teixeira, the main “actress”, and the other “actors.” He decided not only to finish telling the murdered peasant’s story, but also to relate what happened to all those people since the last time he saw them. In doing so, Coutinho created a fascinating narrative that combined the original footage with images of the now-older characters. Meanwhile, Elisabeth, who had gone underground and changed her name to avoid being assassinated, was tracked down by the director, and reunited with the children she’d had to leave behind.

“Cabra Marcado para Morrer” is not only a tribute to João Pedro Teixeira, but also a document about the Dictatorship in Brazil and the personal story of an incredibly resilient woman. It’s also one of the most intriguing documentaries you could ever see.

But that’s just one movie. Eduardo Coutinho created many other masterpieces after that. His trademark, his authorial signature, was his humanity: his kindness.

While he he kept a careful distance from his subjects, allowing his crew to do the preliminary interviews and only approaching the subjects when it was time to actually shoot, he was also a director who quickly fell in love with the protagonists of the stories he helped to tell—and if he didn’t fall in love with all of them, at least he respected them.

While other documentarians often corner, sting, judge and otherwise convey superiority to their interviewees (hey, Michael Moore), Eduardo Coutinho was unable to set traps for those he met. Besides, that was not the kind of nonfiction he enjoyed: the tabloid, the spectacle , the “gotcha” documentaries. Instead, Coutinho loved studying human nature, seeking beauty in the mundane, and extracting poetry from the everyday life of his quite ordinary characters.

His documentaries often used a central anchor that helped structure them: religion (“Santo Forte” a.k.a. “The Mighty Spirit”); poverty (“Santa Marta–Duas Semanas no Morro”), the preparations for the celebrations of the turn of the century (“Babilônia 2000”); the favorite songs of the interviewees (“As Canções”) or, in the case of one of his most brilliant films, the simple fact they lived in the same, colossal building (“Edifício Master”).

From that starting point, Coutinho would dug narratives. In one moment he would touch us by just revealing the sense of nostalgia and loss brought by a cheesy song. In another he would allow interviewees to expose all the nonsense of their beliefs, but without feeling the urge to reduce or ridicule them. In the process, he would create a tapestry of individual folklores.

I loved Eduardo Coutinho for making me love so many people I never met. I loved Coutinho for making me see with tenderness someone who looked proud of being ignorant. I loved Coutinho for making me more human.

In the 20 years of my career, I met the master on three occasions. In 2002 or 2003, I conducted a interview with him for my (now extinct) TV show, a long conversation that covered his entire career. Some years later I encountered him during the Sao Paulo International Film Festival and talked to him for about ten minutes.

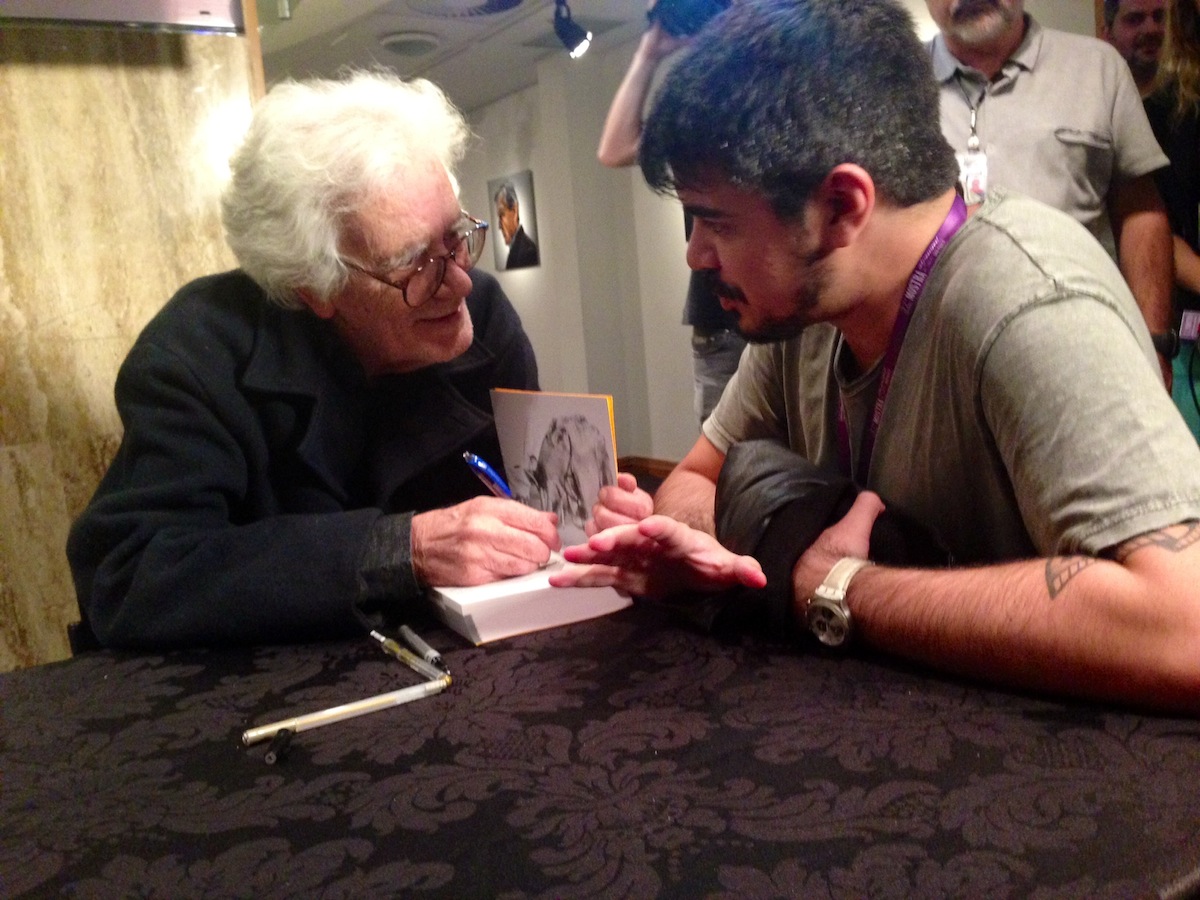

Finally, about two months ago, I went to the release of a book about his work and we chatted briefly (the picture above is from this final meeting ). I repeated then what I had done the previous two times: I told him how much I admired him and loved him for making me a better human being through his films. And I said his humanity was a privilege to witness. (A characteristic he shared with Roger.)

At that time, by the way, he proved once again his love for stories and individuals: before signing each book, he asked the person in front of him to talk a little bit about themselves, since he could not give an autograph without knowing at least a bit who would receive it. This caused a huge line, but ended up being rewarded by the attentive and interested gaze of the master with fluffy white hair and a voice hoarsened by age and cigarettes, who listened with rapt attention each stranger.

He knew the next person in the queue could contain the seed of a new movie.