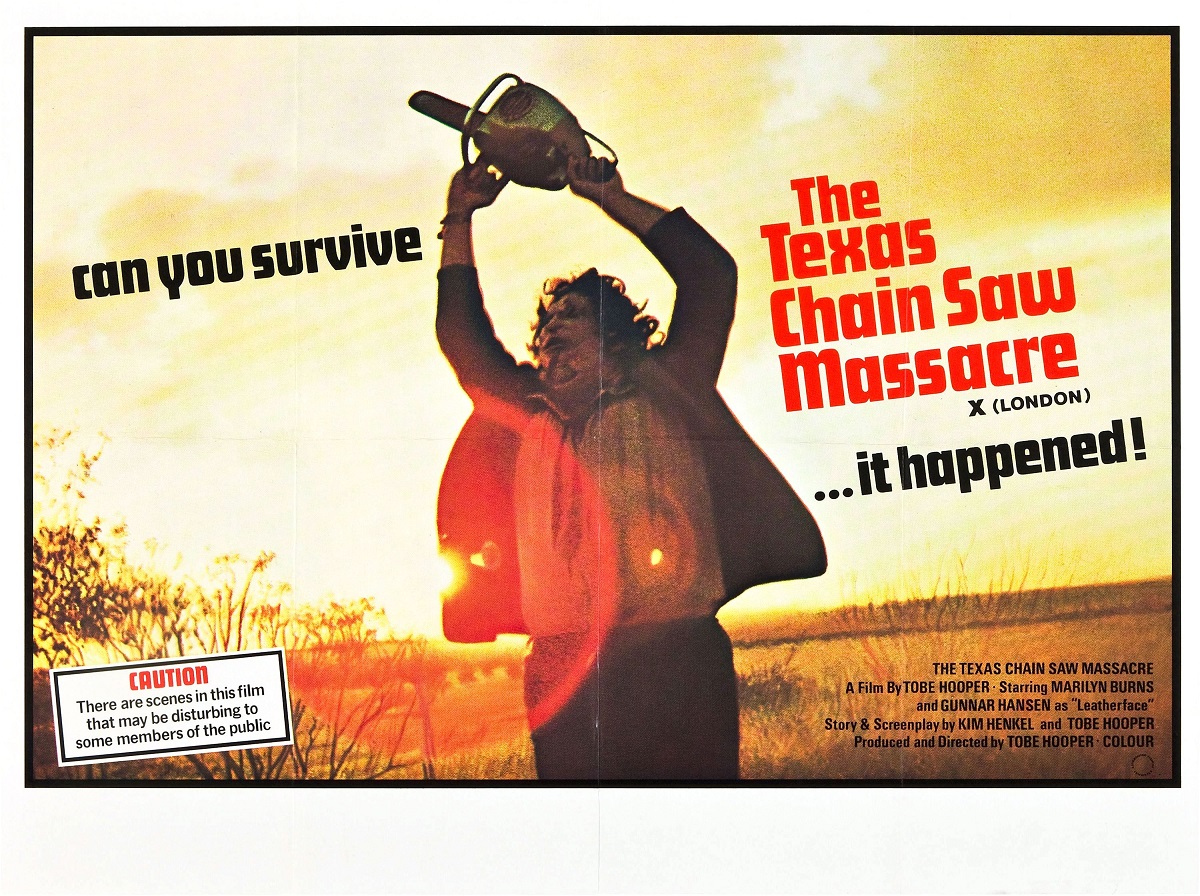

While movie posters primarily serve to hype the films they advertise, some of the original posters for “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” actually tell you a lot about the film. The now-infamous proto-slasher horror film’s most opaque poster is its most popular. It tantalizes prospective viewers by asking: “Who will survive, and what will be left of them?” That tagline inspired a generation of gorehounds, including William Lustig, the writer/director of “Maniac” and “Vigilante,” as well as the founder of Blue Underground, a DVD/Blu-ray label dedicated to sleazy exploitation/horror films like “Zombi 2” and “Mondo Cane.” But some of “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre”‘s other original posters circles around what makes “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,” now 40 years old (and being rolled out across the country in a 4k restored version, starting tomorrow, June 21st, at the Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York), such an enduring horror milestone: it’s partly true. “It happened,” the film’s British poster gasps breathlessly. while an Italian poster warns viewers

“Non E’ Solo Un Film! E’ Realmente Accaduto!’ (“It’s not just a film! It really happened!”).

Think of these taglines as tossed gauntlets. Several preceding

horror films titillated viewers with more graphic, quasi-realistic violence and built their PR campaigns around it. Both Herschell Gordon Lewis (“Color Me Blood Red”) and Wes Craven (“Last House on the Left’) recycled the now-famous “Just keep saying to yourself: it’s only a movie, only a movie, only a movie…” tagline that exploitation king William Castle used to advertise his 1964 psycho-drama “Strait-Jacket.” “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre”‘s poster responds to these ads by further provoking viewers: there’s no such thing as “only a movie.”

Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen), “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre”‘s chainsaw-wielding monster, is partly based on Ed Gein, the real-life Wisconsin murderer and body-snatcher that also inspired “Psycho”‘s Norman Bates, and “The Silence of the Lambs”‘ Buffalo Bill. Arrested in 1958, Gein defiled local graves, dismembered

corpses, and hoarded body parts from 1947-1952. He made clothing, including belts and leggings, out of human skin. Gein was caught soon after he shot and posthumously tortured Bernice Worden, a local hardware store owner. He was tried twice, but only convicted in 1968 of first-degree murder and confined to mental hospital for the rest of his life.

Gein’s mental instability is the source of Leatherface’s disturbing behavior. Director Tobe Hooper and co-writer Kim Henkel made Leatherface an essentially impenetrable monster: his behavior is erratic, and his motives are unclear. When a group of post-Summer of Love twenty-somethings stumble upon him, Leatherface’s existence and violent actions are a given. The only clues we have as to

why he behaves the way he does are his dilapidated home, his cannibalistic family, and his human trophies.

That lack of clear-cut motivation is striking when you compare “The

Texas Chainsaw Massacre” with earlier Vietnam-era horror films. In “Blood Feast,” the first historically recognized “splatter film,” writer/director Herschell Gordon Lewis grossed viewers out in 1963 with a Grand Guignol-inspired murderer that makes human sacrifices in the name of Egyptian goddess Ishtar. The undead zombies in George Romero’s seminal 1968 horror classic “Night of the Living Dead” are only relatively mindless: they live to eat. And the not-quite-hippies that

terrorize Wes Craven’s scuzzy 1972 debut “The Last House on the Left” are even more menacing because they’re comparatively sympathetic thrill-seeking humans. “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” goes even farther than these earlier films by offering a more cynical kind of realistic horror film, one in which the monsters can’t be interrogated or dismissed as supernatural creatures.

While they were working on a tiny budget of approximately $140,000, Hooper and Henkel wanted to make “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” look real enough. Their film, originally titled “Headcheese” and then retitled “Leatherface,” starts with what exploitation filmmakers call a “square-up” title card designed to simultaneously wind up viewers (“…one of the most bizarre crimes in the annals of American history…”) and placate censors (“It is all the more tragic in that they were young”). This introduction tells viewers that “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” is essentially historical fiction. It’s also a precursor to the now-ubiquitous, and much-more succinct “Based on a True Story” tag that haunts virtually every post-“The Exorcist” ghost story. “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre”‘s very first scene teases viewers in a similar way, featuring a radio announcer’s graphic report of Gein/Leatherface’s crimes: “…in some instances only parts of a corpse have been removed, the head or in some cases the extremities, the remainder of the corpse left intact.”

The line between fact and fiction was similarly smudged throughout “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre”‘s fast-and-dirty 32-day shoot. This was partly by design. For example, in order to preserve an element of surprise, Hansen’s co-stars were not allowed to see him in full make-up until their characters were attacked. Art director Robert A. Burns designed the patchwork shroud of flesh that Leatherface hangs over his face so that it would look crude. He dismissed make-up pioneer Tom Savini’s later attempt to improve his own

work in Hooper’s 1986 sequel “Texas Chainsaw Masscare 2.” To Burns,

Savini’s Leatherface was obviously designed by a professional artist. Burns’s Leatherface is a self-made monster. His skin-mask is

sickly yellow and translucent. It seems to have been cured, like leather. That false

face is only held together by wire and wild stitching. It looks real,

like the work of a madman.

Budgetary restraints only made Leatherface even more

terrifying. Hansen prepared for his role by wandering around a special

needs school’s campus, and observed its students’ mannerisms, but that

probably didn’t unnerve his fellow actors as much as his costume did. The film was shot during an Austin summer. Temperatures ranged from 90-100+ degrees.

There wasn’t enough money to buy Hansen more than one outfit, so he

spent twelve to sixteen hours a day in the same outfit. Hooper’s crew couldn’t

afford to clean Leatherface’s clothes; they were supposedly too afraid they would get lost or damaged in the wash. Imagine how Hansen’s pungent

stench contributed to scenes like the one where Leatherface chases Sally

(Marilyn Burns), one of his victims, through surrounding woods, up and

around his family home, then back out into the woods again. No amount of

familiarity with Hansen, a smelly 6’4″ Icelandic giant wearing a

skin-like prosthetic and holding a working chainsaw, makes this scene

less terrifying.

That chase sequence is indicative of the “You are there” atmosphere

Hooper achieved throughout “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.” Today, he

grouses about how people don’t appreciate how macabre his film

is. In fact, both his “Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2” and Henkel’s “Texas

Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation” serve as correctives to that

perceived slight. And yet, to be fair to those who see the original “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” as more horrific than funny, Hooper and Henkel are constantly trying to pull the rug out from under

you, making it impossible to anticipate what’s going to happen beyond

any given scene. Anything conceivably funny about “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” is

funny in a sadistic kind of way. You can laugh at Burns as she’s

terrorized by John Dugan’s blood-sucking, noodle-limbed Grandfather, and you can chuckle nervously at the goggle-eyed looks of disgust that

Edwin O’Neil’s Hitchhiker earns when he cuts his own palm, but these

scenes are seriously disturbing. Any hints of verisimilitude, like when

Hooper shows Leatherface’s first victim twitching on the floor after

he’s bludgeoned with a meat mallet, make “The Texas Chainsaw

Massacre” that much more surreal.

Hooper and Henkel’s original film resists psychological

analysis. Characters attack or are attacked without reason. The mysteriousness of the violence is underlined when Sally naively explains her interest in astrology:

“Everything means something, I guess.” “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre”‘s

creators spend the entirety of their film’s lean 84-minute running time

disproving Sally’s wishful thinking, dropping her into a nihilistic void

in which violence is a pitilessly unexplainable fact of life.