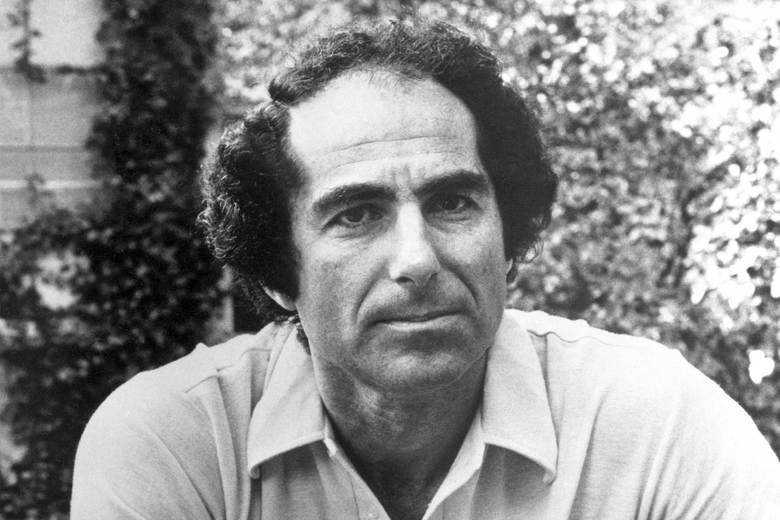

I never read a Phillip Roth book that I did not enjoy. This is an odd thing to say, given that with most authors by which one has read more than one title, there has to be one clunker, or at least one book you prefer over the others, but with Roth: no. Like Doctorow, Oates, and Heller, to name a few writers more or less of his generation, he produces a consistent product: the well-constructed, well-executed novel, whose style and shape will be dependable from one book to the next, and which will almost always, to use a phrase most familiar to people under 45, “go there.” Early novels like Goodbye, Columbus and later novels like The Humbling might show differences in relative aggressiveness but they grow from the same work aesthetic and the same desired relationship with the reader. Much like the greatest films, they pick you up, they draw you in, they show you a world—and the world, usually, is not the world you would have dreamed up. It is a world in which you are morally and intellectually uncomfortable.

The first Roth I read was Portnoy’s Complaint, in college; I had the benefit of having a professor at Columbia read it, out loud, doing different voices, animating it, and at no time did I think it was the least bit odd that a professor was reading, with great enthusiasm, a tale of a prolific masturbator. It was literature. The key there, and the key up until his last books, has always been the individual sentence. Sentences are difficult, and easy to underestimate. I would defy any writer to give the number of redeemable and wholly beautiful sentences they have written in a lifetime—and yet, in reading Roth’s prose, you really might want to try harder to write one, one that lasts in the memory, that starts with a blast of energy, like the beginning of a fireworks display or symphony, and then charges forward.

The tables Roth’s sentences have always been laid out upon, further, are not card tables, but tables that grow out of the earth, constructed out of our deepest, most disturbing thoughts. What if Lindbergh became president? What if body parts were allowed to narrate novels? What if a casual joke in a classroom was misunderstood and destroyed your life? The important thing here is that Roth doesn’t stop with the mere idea, though there are many examples of novels that staked their claim on an interesting idea and didn’t go much further. Roth explores, he prods, he pokes, he questions—the method is philosophical, though he is far from a writer’s writer. It is most significantly a freeing method.

Once the examination begins, Roth can head in any direction he likes, which would explain why, of the American novelists, he is among the most vibrant and entertaining tellers of sociopolitical stories. It would also explain why he wrote so comfortably and so persuasively about sex, about its urges and mishaps, his only equal being Erica Jong. He has weathered significant criticism, as well he should, for his attitudes towards sex writing and towards women in general in his fiction: his visions of the female body read like a combination of Hieronymus Bosch, R. Crumb, and less-inspired Henry Miller. Which is not to discredit these authors! It’s the way the writing is used—to confirm not so much an old boy network as a boy network, and to extend pimply, horny, inner adolescence as long as possible.

And so the reports come in, and the words are familiar—debasement, misogyny, sexism. Repeat offenses. And sometimes there’s a bookfire. Again, wholly justified. BUT. Let’s make a series of hypotheses. Suppose things aren’t going well for you. Suppose the level of frustration you feel has reached an upper limit that is no longer tolerable. Suppose as a last resort you take a book to a park. Suppose that book is The Human Stain. Suppose you stare at it in your state, in your little froth, thinking life can’t be that bad, but it actually might be. Suppose you’ve opened it because all you want, at this moment, is for something to take you out of yourself. Suppose you begin reading and an old familiar sensation takes hold, that of being carried from one line to the next. Suppose you ignore the fact you’re sitting on the grass and your pants are dampening with the condensation. Suppose you just keep reading. Suppose you ignore the bugs flying around your head as you just keep reading. Suppose the sun sets. Suppose you don’t notice until you can’t see the words on the page. Suppose you go to a diner to finish the book and stay there until it’s finished. Suppose at the end of the book you realize that it is evidence that Roth had a higher purpose in writing it, examined the purpose, planned it out, and executed it. Suppose you have some inkling of how hard that is to do, repeatedly, over the course of a life’s work. What then? RIP.