Pretty much every Chicagoan who has traveled abroad has a version of this story: You tell people in India or Japan or France that you are from Chicago and they immediately respond with some variation on “Oh, Al Capone. Bang bang.” Imagine then how Chicagoans, myself included, feel when we learn that the eight-part CNN series with the sweeping, epic-scaled title “Chicagoland” focuses on the undeniably terrible problems with violence and failing schools, especially in neighborhoods that are predominantly home to African-Americans. Is violence and failure the only reputation we have in the world?

The subject is worthy of a series, of course, particularly in the wake of Rahm Emanuel’s closing of 51 schools and the seemingly endless roll-call of shooting victims. Things got so bad a few years ago that the nickname “Chi-raq” became popular. When Emanuel decided to close so many schools, a major concern was that gang territories had been stabilized in neighborhoods such that kids going to school knew whose turf they were on and affiliations protected them. Close those schools and consolidate the population and suddenly kids were crossing into rival gang territory, with those unaffiliated with any gang caught in the crossfire.

“Chicagoland” chooses to tell these intertwined stories by following a few key players in the drama: Mayor Rahm Emanuel, the notorious former Obama Chief of Staff with a penchant for foul language and an approach to politics that might politely be described as no-holds-barred; Garry McCarthy, Emanuel’s choice as Superintendent of Police, who brought a statistics-driven approach to crime response from New York City and Newark, NJ; Elizabeth Dozier, Principal at Fenger High School, who was tasked with turning around a school plagued by violence and painfully low graduation rates. At least in the first four episodes, everyone else is either doing what amounts to walk-ons (celebrity chef Achatz, club owner Billy Dec, the Blackhawks, etc.) or supporting roles (Fenger High senior Leo McCullum, Chance the Rapper, etc.).

This approach makes sense, and the access the filmmakers got is terrific, but everyone comes off as people with the best of intentions bravely fighting a mysterious set of problems that are not given a face. Emanuel should send flowers to the filmmakers; though many Chicagoans now think of him as deploying strong-arm tactics and making troublingly familiar deals that suggest the rich and connected are getting richer because they’re connected, the series shows him as dedicated, energetic, given to the occasional F-bomb and eager to mentor kids. On the other side of the school closing battle is Chicago Teachers Union head Karen Lewis, who also comes across as having the best intentions, and parents deeply engaged with keeping their kids’ schools open. That’s inspiring, but oversimplifies the problem and makes it rather puzzling to viewers not well-versed in a lot of the minutiae of what was going on during the school closing battle.

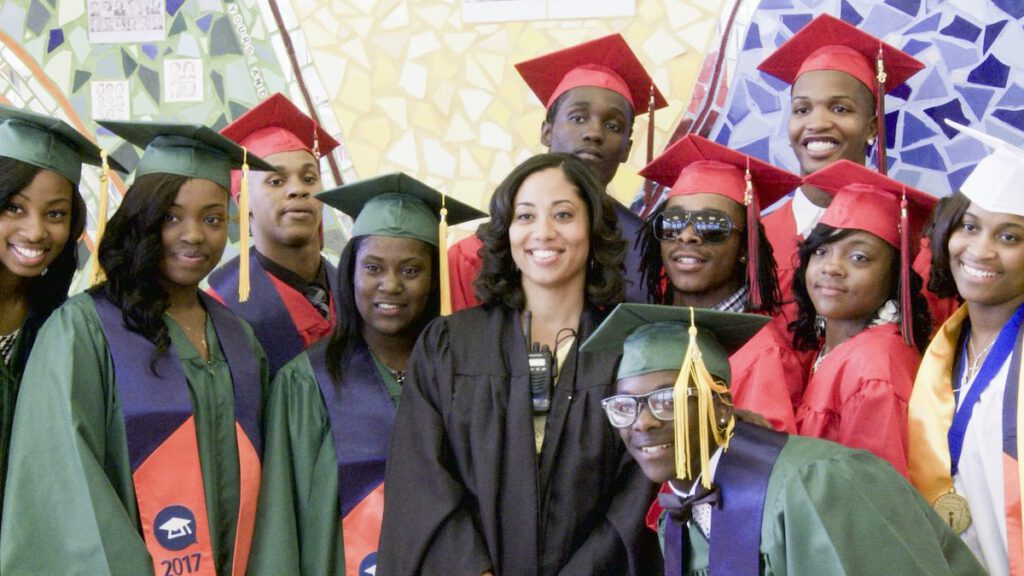

The focus on personalities makes for good drama, and you can’t help but being awed at the energy and dedication of Elizabeth Dozier, who becomes the real hero of the first four episodes. She’s tireless: visiting a former student in jail and doing everything in her power to get him a second chance, walking the streets around her school after the final bell to check in with kids on their way out into the danger zone, trying to squeeze everything she can out of dwindling funds to keep her turned-around school on track.

But after a while, it feels as though some things are missing, and their absence is deeply felt. Serious analysis of the problems isn’t on the menu. We get some troubling statistics (In Chicago in 2012, three quarters of all murder victims were African-American, though African Americans make up only a third of the city’s population), but no deeper look at causes or systemic problems. And since the series shows ‘good actors’ doing good actions for seemingly all the right reasons, we’re left with a telling absence; where are the voices of the people doing the shooting? You’ve heard of victimless crime, but this series is all victims and heroes, with no perpetrators or sense of what their lives are like.

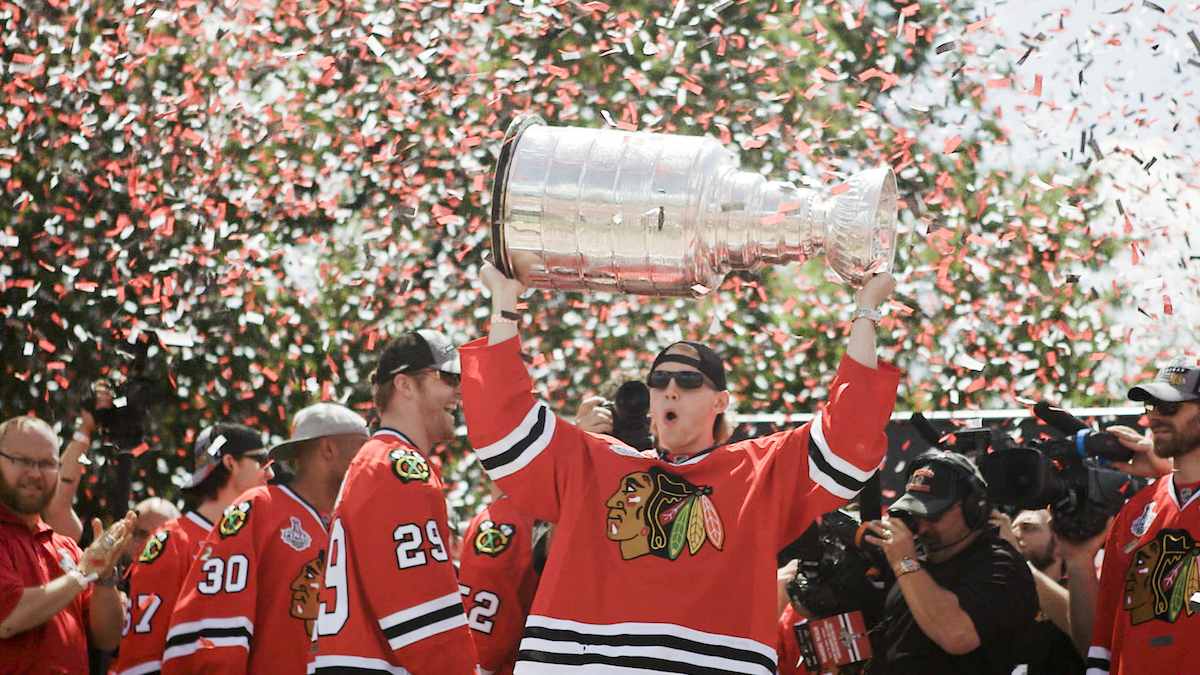

The over-simplification is reinforced by the filmmakers’ choice to add contextual pieces acknowledging other aspects of the city’s daily life. Every fifteen or twenty minutes, we’ll get something like “meanwhile, the city is gearing up for the NHL playoffs, and Blackhawks fans are excited”, punctuated with shots of predominantly white crowds drinking at one of Dec’s bars and cheering on the Blackhawks. Then we cut back to the grim realities of violence on the South Side. Next up, the city welcomes Lollapalooza (quick interview with Perry Farrell), and meanwhile, at Fenger High School, Dozier tries to save a kid from gangs…The result, intentional or not, is to make it look like there is real life—the dangerous streets of the South Side—and a bunch of oblivious drunk white people at sporting events and concerts. Yes, Chicago is one of the most segregated cities in the United States, but by including these little punctuations, “Chicagoland” seems to make a claim to being more comprehensively about Chicago as a whole than it actually is.

That’s not to say that this isn’t interesting television. Emanuel, love him or hate him, is fascinating to watch as he adjusts his talk to fit his audience, from little kids to cops to administrators to celebrities. And Elizabeth Dozier ought to have been the subject of a whole series of her own. But by its title and its intermittent claims to being about the city as a whole, and by making the story of violence and schools about a small group of personalities, “Chicagoland” feels like a bigger, more emotionally engaging version of “Al Capone. Bang bang.”