1.

“The Marx Brothers’ Lost Film, ‘Humor Risk’: Getting to the Bottom of a Mystery“: Matthew Coniam and R.S.H. Tryster investigate at Brenton Film.

“‘Humor Risk,’ the first ever Marx Brothers film, was here and then, seemingly, it was gone – almost immediately. But as reputations go, ‘Hats Off’ (1927) or ‘London after Midnight’ (1927) it is not. We’ve called off the search, if indeed it was ever on. Whenever those lists are made of the most keenly desired lost silents, there it always is: somewhere else. There are two main reasons for this: aesthetic and practical. The former seems to me somewhat misguided. In the first place, we don’t actually know it’s lousy. We are, I think, far too willing to allow Groucho’s own famously self-deprecating judgement of the film to condition our own. Odder still is the tendency to offer the fact that it’s silent, and that the Marxes are by most accounts not playing even an approximation of their established roles, as fatal drawbacks. Each to his own, of course, but to my mind these aspects of the film are high among what makes it so desirable. Though the idea of a silent Marx Brothers seems an absurd one, it nearly happened on several other occasions. There was the offer from First National that got as far as an announcement in 1926. Then an overture from MGM to make a series of comedies (presumably meaning screen originals) as close to the wire as 1928. And then the screen test by United Artists, for a proposed version of ‘The Cocoanuts’ itself, a full year before Paramount took them up. Had the latter happened it would almost certainly have been largely if not entirely silent. As well as these near misses, the New York Evening Post reported in 1928 that the Brothers ‘have been offered a staggering sum by a moving picture company to appear in a screen burlesque on the life of Napoleon Bonaparte’, with Harpo as Napoleon, Groucho as Wellington, Chico as Blucher and Zeppo as King William of Prussia. (Alas, they ‘are said to have refused the offer, at least for the time being.’) And that’s not counting both Harpo’s and Zeppo’s encounters with the silent camera, both in 1925, in ‘A Kiss in the Dark’ and ‘Too Many Kisses,’ respectively. (Actually, it’s been claimed that Zeppo can be seen as an extra in ‘Too Many Kisses,’ too, though the word hasn’t travelled far as yet. But it’s Paramount’s ‘Behind the Front’ [1926] that features the first sighting of an authentic Marx routine in the movies, and it doesn’t involve any of them. As Variety noted: ‘One of the laugh hits of the picture, where the pick-pocket drops a lot of knives and forks from his sleeves has been taken bodily from ‘I’ll Say She Is.’ It’s a Marx Brothers bit.’)”

2.

“Remember the Warriors: Behind the Chaotic, Drug-Fueled and Often Terrifying Making of a Cult Classic“: An excellent piece from Jackson Connor at The Village Voice.

“In the ensuing three-plus decades following the film’s release, New York City, on many levels, has become virtually unrecognizable from the gritty version portrayed (realistically, at the time) in the film. Perhaps because of this, the film has, over the years, earned the sometimes dubious status of ‘cult classic.’ By the time the film was set to hit theaters, in February of 1979, gangland America had become a powder keg ready to explode. But for the first time, a film did not seek to explain away gang violence, nor rationalize its existence through bourgeois social theory. Instead, ‘The Warriors’ attempted to present the experience of America’s downtrodden youth as it was, with no moral judgment. ‘With film and literature on street gangs there tends to be two different voices, two different kinds of views,’ says Sudhir Venkatesh, a professor of sociology at Columbia University and author of Gang Leader for a Day: A Rogue Sociologist Takes to the Streets. He uses ‘The Warriors’ to teach one of his courses. ‘One is the social problems: ‘Why are these kids in this and how do we get them out of it?’ The other one is the idea of looking at street gangs as modern-day knights — that [they exist] out of this purported universal need for men to defend their group. I put ‘The Warriors’’ aesthetic vision in that camp. In the modern-day city, this is valor.’For many troubled young people, ‘The Warriors’ would mean seeing a part of themselves reflected onscreen for the very first time, the film’s director, Walter Hill, tells the Voice today. ‘Our film doesn’t say everyone is supposed to be a lawyer or a doctor or something,’ he says. ‘The movie sees gangs as a defensive alignment in order to help you survive in a harsh atmosphere.’”

3.

“‘The Diary of a Teenage Girl’ and the Necessary Audacity of Creative Confidence“: Marielle Heller discusses her astonishing directorial debut with Fast Company‘s Joe Berkowitz.

“‘Something I truly related to with Minnie was being an artistic kid who was making projects out of everything in my life, coping with whatever life sent my way by making art,’ says Heller, whose mother was an art teacher. ‘I was one of those kids who spent a lot of time alone in my room making things, so it was something I really clicked with in this character.’ One crucial difference between the character, who is portrayed by British actress Bel Powley, and her eventual screenwriter, though, is that while Heller’s talent was nurtured from an early age, Minnie’s is not. The people in her life look at her drawings and don’t acknowledge them. Her love interest—who, by the way, is also her mother’s boyfriend—looks at Minnie’s drawings, deems them freaky, and shames her for them. Nobody else gives her any indication that she should continue what she’s doing either. It’s an artistic existence with no validation from within or without. External validation is a double-edged sword, though. It can make up the stars that a young artist steers by, or it can serve as a destination unto itself. Heller seems to opt for the first scenario. ‘I don’t think it’s wrong to base your confidence at least in part on what other people think,’ she says. ‘When you make the kind of art that is solipsistic and alone, you need people to encourage you, because it can feel like a totally useless act otherwise. You can feel like you’re working in a void. I know when I’m writing, until someone reads the pages I’ve written, I don’t feel like I’ve written them at all.’ The lone ray of light in Minnie’s artistic life in the movie arrives when much-beloved comic artist Eileen Kaminsky eventually responds to Minnie’s letters and encourages her to continue drawing. Once Heller decided she wanted to bring ‘Diary of a Teenage Girl’ to life, though, she did not receive any commensurate reassurance right away.”

4.

“‘I Was Definitely Curious About What It Would Mean For My Career’: David M. Rosenthal on ‘The Perfect Man’“: In conversation with Jim Hemphill, writer of the invaluable “Focal Point” series at Filmmaker Magazine.

“Filmmaker: ‘Let’s talk about the visual style of the film. I love the look of the movie, especially the use of anamorphic lenses.’ Rosenthal: ‘I think about lenses right from the beginning in prep, partly because I come from a photography background and studied cinematography at AFI. In fact, it’s a little tricky, because I always have to have a conversation at the beginning with my D.P.s explaining that I’m never going to get in their kitchen, but I am going to be heavily involved in a lot of the choices that are normally their domain. In the case of ‘The Perfect Guy,’ I knew we were shooting digital, and one of the things that irritates me about a lot of digital work is that it’s hyper-resolved. You lose that magical quality that you get from photochemical, especially in the day exteriors. We shot on the F65, which is a good box with a good sensor, but I wanted to use vintage anamorphic lenses and lose some resolution, and get that beautiful creamy look you get from true anamorphic. Optically, at the top and bottom and in the corners you get a little fuzziness, which I find inviting as a viewer. I really wanted the Panavision C series, but they’re impossible to get – they were on ‘Star Wars’ at the time, and the biggest directors have them on hold for months in advance. As soon as I got the job on ‘The Perfect Guy,’ I asked the studio to get in touch with Panavision and see if they could get the C lenses, but they couldn’t. So the cinematographer Peter Simonite and I started looking at Hawk lenses, and they had a new set that mimicked vintage anamorphic. That’s what we ended up using.”

5.

“The Home for Hollywood Dreamers and Dropouts“: At Narratively, Shawna Kenney pays tribute to an unforgettable Tinseltown tenement.

“In the mid-90s, my new boyfriend and I moved from our hometown of Washington, D.C. to California together, sight-unseen, in our twenties. Fresh out of college and wielding a film degree, I moved to Los Angeles to work in the movie industry, which I decided I hated after a stint as a production assistant. But we loved the weather and the produce and the laid-back culture, so I took a boring office job while freelance writing on the side; he played guitar in a punk band and held a day-gig in post-production. We answered the ad, landing in a studio apartment in this rent-controlled, unidentified art-deco building on a dead-end two blocks north of Hollywood Boulevard, just over the 101 Freeway. When a longtime Angeleno friend came to visit she recognized our building — it was the subject of a poem she’d written in the eighties entitled ‘Tamarind Arms,’ its old name. In it she described the dingy hallways and ‘carbohydrate smell’ of the building where people once bought heroin simply by driving up to a first-floor window for their transactions. It had a title at least back then, though it had somehow lost it since. Later we recognized its address on a map in the back of the book Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder, about Elizabeth Short, the forties-era twenty-two-year-old found brutally murdered in a grassy Hollywood field. The Tamarind Arms was the only structure in the area at the time, a party hotel popular with young actors and apparently one of the Dahlia’s many hangouts. It must have been fashionable to christen your hotel with some dramatic description, as evidenced all over the signage of Hollywood’s sun-bleached architecture. Who could feel like a failed entertainer when gazing out the windows of the Starlet Inn, the Shangri-Lodge, L’Amour Arms or the Montecito?”

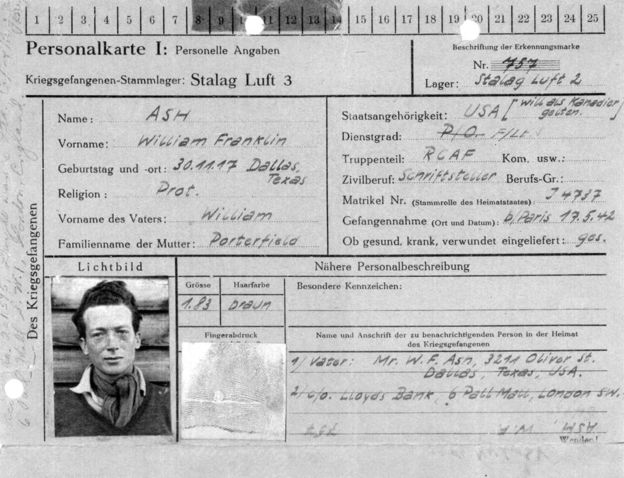

Image of the Day

At BBC, author Patrick Bishop explores the life of William Ash, who served as the model for Steve McQueen’s character in “The Great Escape.”

Video of the Day

At this year’s SXSW festival, Mark Duplass delivered a terrific keynote speech before answering questions from audience members, one of whom just happened to be Gail Bean, star of Kris Swanberg’s wonderful film, “Unexpected.”