1.

<img src="https://static.rogerebert.com/redactor_assets/pictures/526e5f5e4206c541cc000001/Unknown.jpeg" style="“>

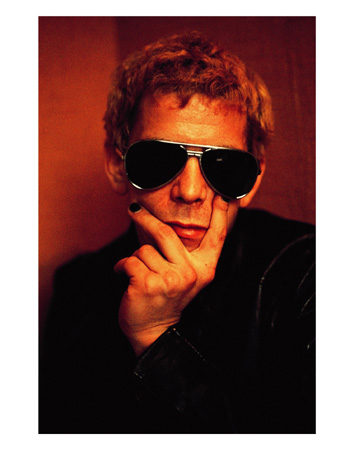

Lou Reed, he who (grudgingly) influenced the last 50 years of rock and roll, has died. The punk rock nation and its descendents reel, and some of our finest music critics have stepped up mightily to toast their antihero. For Rolling Stone, Jon Dolan writes “Lou Reed, Velvet Underground Leader and Rock Pioneer, Dies at 71.” For NPR, Ann Powers writes “What Lou Reed Taught Me.” For CNN, Michaelangelo Matos writes “Today’s Rockers Stand in Lou Reed’s Shadow.” From Spin, “Toesucker Blues: Robert Christgau’s Farewell Salute to Lou Reed.”For The New Yorker, Sasha Frere-Jones writes “Postscript: Lou Reed.” For Vulture, Jody Rosen writes “A Pop Star for Adults.” For The Daily Beast, Legs McNeil writes “What Lou Reed Was Really Like.” Even Salman Rushdie takes a moment for Lou, and The Guardian republishes the late music critic Lester Bangs’ finest interview with his hate-love. Finally, lest we forget Lou’s never-ending self-invention: the murder-mystery he wrote for The Paris Review.

2.

For The New York Times, Manohla Dargis outlines the problems presented by the Abdellatif Kechiche-directed Palme d’Or winner: namely, viewing a lesbian teen romance with the male gaze (though she carefully sidesteps that feminist chesnut of a phrase). See also: For Indiewire, Judith Dry‘s “‘Blue Is the Warmest Color’s’ Lesbian Sex Scenes Are Hot But Boring” and this NPR interview with queer feminist film critic B. Ruby Rich: “For ‘Blue,’ The Palme d’Or Was Only The Beginning.”

“In truth, it isn’t sex per se that makes ‘Blue Is the Warmest Color’ problematic; it’s the patriarchal anxieties about sex, female appetite and maternity that leach into its sights and sounds and the way it frames, with scrutinizing closeness, the female body. In the logic of the movie, Adèle’s body is a mystery that needs solving and, for a brief while, it seems as if Emma will help solve it. In “The Second Sex,” Beauvoir wrote that “the erotic experience is one that most poignantly discloses to human beings the ambiguity of their condition; in it they are aware of themselves as flesh and spirit, as the other and as the subject.” This is the ideal, but for Adèle, the erotic experience leads to despair, desperation, isolation. The body betrays her — just like a woman.”

3.

For Senses of Cinema, Matthew Asprey Gear surveys some biographies of Orson Welles, and considers whether the late helmer would have approved of them.

“Although Welles never finished writing a full-length memoir, on several occasions he accepted large advances for various autobiographical book projects. Like his fees for acting, voice-over work, and presenting television commercials, the money helped pay his considerable expenses and fund his independent projects. ‘I’m negotiating a new contract for a book,’ he told Roger Hill on the night of his death in 1985. ‘I really need to write volumes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 of my memories [sic.] to make enough money to finance my movies!’ Others paid back the advances when the books failed to materialise. Welles was also interested in how a well-timed book might alter the public conversation. As his friend Peter Bogdanovich recalled, ‘the often grossly inaccurate stories and exaggerated legends told of Welles’ exploits made it that much tougher for him to work as a filmmaker.’ Badly researched or even vindictive books by Charles Higham and John Houseman, and Pauline Kael’s now-discredited New Yorker essay ‘Raising Kane’, had damaged Welles’ reputation in the early 1970s; he needed counter-punches more substantial than op-eds under Bogdanovich’s by-line. Yet, for a predictably complicated variety of reasons, none of these varied book projects were finished in Welles’ lifetime. Bogdanovich’s interviews, conducted between 1969 and 1972, perhaps the earliest stillborn book project, were finally published as This Is Orson Welles in 1992. As edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum, it is still unsurpassed as a first-hand discussion of Welles’ work.”

4.

“Is the Search for Consensus Ruining the Way We Talk About Film?” For The A.V. Club, Jesse Hassenger wonders if the nearly unilateral praise for “Gravity” stems from something besides the fim’s impeccable appeal.

“As long as movies have existed, predicting what movie audiences will like has been something of a fool’s errand. The best most people can do is tell you what movie audiences like right now. This month, we can say for sure that they like Gravity. Look no further than the metrics for determining audience approval: second-weekend staying power and CinemaScore grades. “Gravity” dropped less than 23 percent in its second weekend, an almost unheard-of figure for a splashy studio movie that opened to more than $55 million the weekend before. For a big-budget, widely advertised film like this, a drop of 50 percent would be routine; a drop of 40 percent would be encouraging. Twenty-three percent is practically a divine miracle. Plus, to seal the deal, Gravity received a CinemaScore grade of A- from paying audiences. It’s settled, then. Everyone likes “Gravity!” It’s been statistically proven.But hold on. A highly unscientific Twitter search of the words “Gravity” and “boring” yields endless tweets of dissatisfaction from paying customers, with very few of them talking about how boring the Newtonian scientific phenomenon is.”

5.

“The Song of Solomon.” For Grantland, Wesley Morris addresses the powerful “cultural crater” of “12 Years a Slave,” which he refers to as a “rare sugarless movie about racial inequality.” (Man, this piece is good.)

“McQueen isn’t the first black director to do a slavery movie. He’s not even the first one to make this one. Gordon Parks actually made Solomon Northup’s ‘Odyssey,’ an earnest, sanitized 1984 PBS American Playhouse production that I saw in elementary school about a dozen times when it was renamed ‘Half Slave, Half Free.’ Haile Gerima’s didactic, highly mystical Sankofa, about a fashion model transformed back in time to an American plantation, made film-festival ripples in 1993. And Gilbert Moses directed a quarter of ABC’s ‘Roots,’ the cultural event of 1977. McQueen’s film doesn’t have that show’s scope (Roots was broadcast on eight consecutive nights in a bygone era of monoculture), its retroactive camp, or its urgent need for racial reconciliation. The power of McQueen’s movie is in its declaratory style: This happened. That is all, and that is everything. No performance is bigger than it needs to be except perhaps that of Fassbender, who plays a dangerously silly man as though he were a dingo. McQueen has the character drunk on power, which allows Fassbender to cut a figure of flamboyance, a man who loves performing ownership.Other actors come and go — Woodard, Quvenzhané Wallis, Chris Chalk, Michael Kenneth Williams, Brad Pitt — but it’s Ejiofor’s stoicism that stays with you. In other movies, he has managed to act past ridiculousness (he originated the drag queen in the movie that became the musical ‘Kinky Boots’) or rivet you with righteousness. Here Ejiofor has the challenge of being solemn without seeming passive. His isn’t that dignified detachment that some actors have to go for with a film like this. He doesn’t have to be a non-human deity. (That was some of the trouble with the Jackie Robinson we got in ’42.’) Ejiofor has a leading man’s carriage. He moves from scene to scene in a state of forlorn rumination. After the opening minutes, McQueen doesn’t waste time with flashbacks. He doesn’t need to. The movie’s right there in that woebegone face.”

IMAGE OF THE DAY

The Factory’s dearly departed king and queen, via Signs and Sirens.

VIDEO OF THE DAY

“Rock and Roll Heart,” the American Masters doc about Lou.