Sundance’s reputation for cultivating interesting filmmakers is by no means a domestic-only effort, as proven again by this year’s World Dramatic Cinema lineup. In its first two days, the festival has presented the world premiere of two different films from vastly different writer/directors, but whose projects are united by an interest in challenging viewers with primary elements like pacing, character and atmosphere. “Pop Aye” and “Free and Easy,” from Thailand and China, respectively, are two competing titles that offer strength in vision from their respective filmmakers.

Selected as an opening night film for the festival, “Pop Aye” is a charming, ambling mid-life crisis about a city architect in Thailand and the elephant from childhood he is reunited with. It’s a loaded pitch, and given a thoughtful execution from writer/director Kristen Tan. The elephant is a great hook, as beautiful and compelling as the animal is, but the story boasts a striking human element that does not bank on sympathy.

Tan is a writer/director who is thrillingly playing with risks. “Pop Aye” challenges a lot of the conventions a viewer might expect from a movie about a man named Thana (Thaneth Warakulnukroh) and his elephant (Bong) on a journey. For one, though the actor who plays Thana makes him initially sweet, a graying man with glasses and an endearing gentleness towards his massive animal friend, seeming like an underdog being pushed out of the city architecture business due to gaudy new ideas, Thana is not an entirely sympathetic character, especially with the way that he thinks of women, despite his charitable, sincere actions in other ways. His strained relationship with his wife is especially cringe-worthy.

In a way that gives the film its own energy, it is not a tidy film with how it treats people or shares its big heart, adding further credence to this story being more like, in animal movie terms, “Au Hasard Balthasar” than “Operation Dumbo Drop.” The movie gains charm from constantly complicating characters one might assume to be simple pit stops.

When telling this story, one risk that doesn’t work and might provide some confusion is the non-linear editing. It challenges the straightforward idea of a journey with reflections of the past, but doesn’t have the clear cut nature to be determined. There are some logic loopholes too (which can’t be spoiled, but you might notice them) that hold back this type of tight depiction of unpredictable, real life that it wants to be.

“Pop Aye” is able to occupy its own tone, in which it isn’t particularly funny or a huge downer, despite its potential to take either path. It paints some thoughtful images, especially as its theme of urbanization comes beautifully with the idea that things change permanently, in spite of our pain from the past that we carry in the present. It’s quite a treat to see this all play out as a story about a man and his elephant, with no heavy-hand in sight.

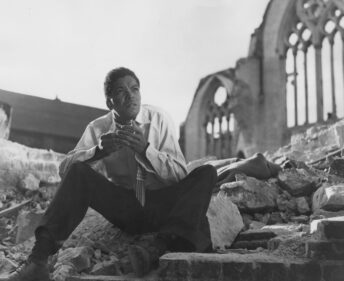

“Free and Easy” imagines a world where people seem to be inherently bad; it would be a cold, empty, lifeless place. The setting is a Chinese industrial town that was beat up and left for dead—as introduced with somber location shots of a horrible nothing. It’s a striking empty canvas that director Jun Geng presents the audience with, only to then add slight brushes to it with a few characters and their acts of manipulation. Many of the characters have their schemes, but with seemingly no other world for them to strive for, it’s more akin to survival. If this movie takes place in a world that seems post-apocalyptic, it is also that of post-empathy, post-warmth.

It’s by no coincidence that “Free and Easy” is designed with the openness and lawlessness of a western. But it’s not a cowboy who rolls into town in the beginning, its a traveling soap salesman (Zhang Ziyong), who offers free soap to people that knocks them out when they smell it—enough time to rob them. He’s revealed to not be the only con in the area, which is populated with the likes of a monk who offers talismans (Xu Gang), a Christian who offers prayer (Gu Benbin) and a man whose bizarre job is planting trees (Xue Baohe), but someone keeps stealing them. As the script further elaborates itself, you can see some overly-calculated allegorical ideas, where power moves are currency. The characters with the most dialogue are not particularly sympathetic, but you don’t want the worst for anyone. And the way they are connected makes for its more memorable passages, and a surprising third act that registers as extremely dry comedy.

Even as the movie resists action, watching Geng’s vision with script and character unfold is often enough to hold interest. Characters take on the attributes of the environment he’s set them into, and speaking very little between extended beats. When they do interact, they’re blocked like statues facing each other, with Geng’s static camera allowing his memorable casting choices to linger. The ideas that he gives them, some of them better sponsors of his poetry than others, makes for a film that’s rich in atmosphere. Though I’d love to see what Geng does with a lot more, the spaciousness of “Free and Easy” is one of its most striking traits.