One of the most asked questions of Sundance 2015 is going to

seem like a simple one—“Would you be a prisoner or a guard?” And, of course,

that opening salvo will lead to deeper questions of how far one would go or how

much abuse one would take in each role. Kyle Patrick Alvarez’s “The Stanford Prison

Experiment” has been compared to Craig Zobel’s Sundance hit “Compliance” in the

manner in which it provokes similar post-screening conversation, but this film

is both more ambitious and less accomplished than Zobel’s work. Alvarez is

trying to capture something not just about human behavior but the institutions

that shape it, and he mostly gets there. There’s a tighter, better film within

this 122-minute version, but there’s more than enough meat on the bones of it

as is to consider it a success, even just as a conversation-starter, a category which has been under-populated this Sundance.

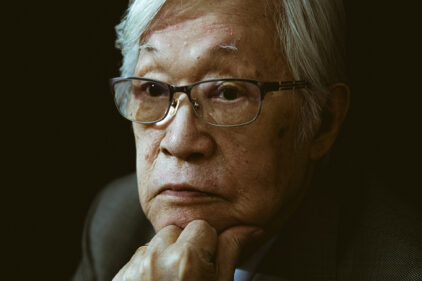

In this true story, Billy Crudup, in a nice comeback with strong work in “Rudderless”

and now this, plays Dr. Philip Zimbardo, a Stanford University professor in

1971 who initiates what will become one of the most famous social

experiments of all time. Working with a few select colleagues, mostly in what

looks like secret in a basement, Zimbardo recruits about two dozen male

students with an offer of $15 a day for two weeks. What’s the assignment? They

will recreate a prison environment—half will be guards, half will be prisoners.

The guards are told not to touch the prisoners, but they’re given a lot of

freedom otherwise. Chosen by a coin flip as to which side they’re on, the men

are divided, and the “fun” begins.

By the end of DAY ONE, things have gone horribly awry. An

overzealous guard named Christopher thinks he’s a combination of John Wayne and

the law in “Cool Hand Luke,” and acts accordingly. He clearly enjoys playing mind

games with his “prisoners,” forcing them to identify only by number and mentally

abusing them. An outspoken student named Daniel (or #8612) (Ezra Miller) pushes

back and gets thrown in the “hole,” which is actually a closet. While it’s

clear that these men are just in rooms in the basement of an academic building,

the conditions are designed to replicate prison and the human mind responds almost immediately. They get no sunlight, lose

track of time, and their wills are quickly broken. And Zimbardo watches the

whole thing, even going as far as holding parole hearings for those who want to

leave.

Based on the emotional and physical abuse that takes place,

it’s hard to argue that Zimbardo’s experiment “worked” (and it feels like

something that would result in multiple lawsuits and “Dateline NBC” specials

were it attempted today) and yet the lessons learned here influence behavioral

studies to this day. So was it worth it? Things got bad on day one and were downright frightening

by day two. And it went both ways. Guards abused power; prisoners discussed

revolt almost immediately. Of course, the people behind the study started to

question what they were doing, and Zimbardo was advised to stop, but he let

things get to their breaking point before they do.

Thematically, “The Stanford Prison Experiment” clearly has a

lot to present about not just male aggression but what being imprisoned does to people (Nelsan Ellis is phenomenal as an ex-con who tells Zimbardo that they need to “teach these boys of privilege what a prison is“), but writer Tim Talbott hits a few too

many of the film’s themes repeatedly, just to make sure you get them. It’s hard

to imagine a more subtle version of such an extreme story, but the film starts

to feel a bit like a carefully calculated lesson more than an organic piece of storytelling. It doesn’t elevate the inevitable in a way that’s memorable. What rescues the script is that Alvarez

wisely cast the piece with an array of talented young stars; Angarano, Miller,

Keir Gilchrist, Thomas Mann, Tye Sheridan, and Johnny Simmons all do excellent

work here, among others. There’s not a weak link (and it’s nice to see Olivia

Thirlby get a few solid scenes for the first time in too long).

As for structure, it’s tempting to say that “Stanford Prison” needs to lose

15-20 minutes to work, but Alvarez is in the tough position of having to

capture the passing time of a multi-day experiment, along with how the

aggressive behavior of these trapped men continued to escalate. Oddly enough, “The

Stanford Prison Experiments” alternately feels like too much and too little. It’s

too much in the sense of pure length, but too little given its cast of dozens,

many of whom start to blur together. It’s a subject that would have been truly

suited by a mini-series, maybe even something as ambitious as an episode for

each day of the experiment. As is, it feels like a starter—to learn more about

the experiment and to start conversation—more than a complete work on its own. Me? I think I’d be a guard, but who knows?