The emails have been arriving with depressing regularity. Often the subject line is only the name of a friend. With dread I know what the message will contain: That person has died. In recent weeks there have been seven such losses. Three came in a 10-day period, and I fell into sadness.

The first death that registered in my life was my Aunt Hulda, my father’s sister, who was laid out in the front parlor and I was allowed to kneel at the coffin, cross myself, and say a prayer before this strange, pale, motionless body. More than ten years later, my grandmother died. I was in high school now, and this death was more real. When my father died at the beginning of my freshman year in college, that was a blow to my existence. He had been the towering figure in my life.

Later many others died, as is inevitable. The public death that had the greatest impact was the assassination of John F. Kennedy. He stood at the head of my idea of America, and I felt then and still feel that some kind of compact had been broken between history and myself.

In the 1980s, my best friend in Chicago died. He had given me my critic’s job at the paper, but much more important than that, he had possessed such a huge personality that all of us in his circle were stunned. Not a day goes past when I don’t think of him. Then my mentor as an undergraduate was killed by a car when crossing the road. All of my writing, whether he read it or not, had been instinctively done with him as my audience. In 1999 my partner Gene Siskel died, and it was almost unthinkable that such a presence had ended.

But let this not be a listing. I miss them all. But these recent deaths have seemed to threaten my idea of who I am and the life I have lived. They are contemporaries. They are reservoirs of memory, and in an important sense all that we are is how we are remembered.

Two cousins from downstate died recently. I attended both funerals. At the first funeral, the other cousin was not only there but uncanny in the way he still resembled the kid I’d grown up with. Oddly, many of my memories were of him playing his accordion on Christmas Eves in that selfsame parlor where Aunt Hulda had been waked.

A few weeks later, I received the unexpected news that he had been diagnosed with cancer. Unthinkable. He had seemed so filled with life and spirit. Now I learned, in a phrase we’ve all heard, “they found the cancer had spread, and they closed him up again…”

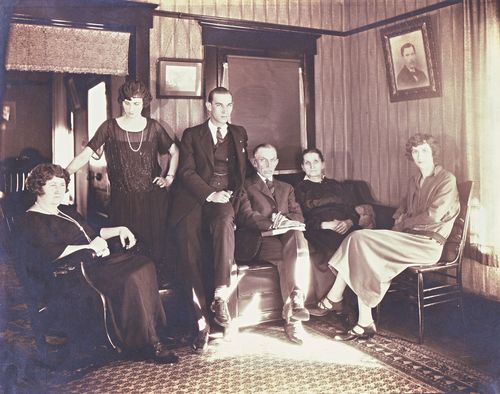

At that second funeral, they had a wonderful slide show of family photos on a big screen TV. Looking at one old photo, I was startled, and waited for it to come around again. I pointed at the screen and started to write a note to explain, but it was no use: Now that this cousin had died, there was no one in the room who would have understood–not even his own younger sister.

The photo showed a family gathering in front of a small house in North Champaign, on some land where there’s now a shopping mall. In the second row, much taller than anyone else, was Uncle Ben. He was married to Aunt Mame, my father’s oldest sister. He drove an oil truck, and when he passed our house he sometimes tooted his horn and I’d run out in front and wave.

He was high above me in the cab of the truck, a considerable figure. He smoked cigars, which I found odd and unusual. I remembered him being tall, but in childhood everyone seems tall. In the old photo, I realized how tall he really was.

I think there’s a chance I was the only person in the room who knew it was Uncle Ben in the second row. There were probably a dozen who knew in general who the picture showed–ancestors on the mother’s side–but does the name or an idea of Uncle Ben linger on earth outside my own mind? When I die, what will remain of him?

Memory. It makes us human. It creates our ideas of family, history, love, friendship. Within all our minds is a narrative of our own lives and all the people who were important to us. Who were eyewitnesses to the same times and events. Who could describe us to a stranger.

Last week the wife of that great Chicago friend died. That death struck me with particular force, because they were so much at the center of my earlier years in Chicago. It was her husband who was instrumental in convincing me to go in 50/50 with them on a little duplex in the woods in Union Pier, across the lake from Chicago in Michigan.

“You’re not going to see these prices again,” he told me. He was correct. For $25,000 we bought a two-family A-Frame on a third of an acre with a path giving beach access. That would have been in about 1979.

They were people who others gathered around as if by instinct. We had a Chicago pal who had moved out there, a photographer and carpenter, and my friend ordered a big wooden deck. “How big?” “As big as the eye can see, around a fire pit.” “How big should that be?” “Big enough to roast an ox.”

At that corner cabin in the Michigan woods a dozen friends, maybe two dozen, would gather for events at which we were essentially celebrating our friendship. “I’ll light a candle in the window,” he’d say, and he always would–to be our guide in the forests of the night.

In the same period of ten days, another friend of 40 years died. He was a Chicago newspaperman, a tall, laughing man with a tall, laughing wife. In our crowd you had better laugh easily, even at the same old stories, repeated time and again. The couple who shared the house with me had a young son. This boy and the newspaperman instinctively bonded on occasions like the Fourth of July. They would drive over the state line into Indiana and bring back grocery sacks filled with fireworks, and prowl the far reaches of the lawn shrouded by smoke, sitting off rockets which sometimes whizzed alarmingly low over the deck.

There would always be a fire in the pit, not for warmth or to roast an ox, but because since the invention of time humans have gathered in circles to gaze into the flames and ponder their mysteries. My friend said, “Every cabin in the woods needs an outdoor fire pit.”

And now my friend’s wife and the newspaperman have both passed away. Early one morning, unable to sleep, I roamed my memories of them. Of an endless series of dinners, and brunches, and poker games, and jokes, and gossip. On and on, year after year. I remember them. They exist in my mind–in countless minds. But in a century the human race will have forgotten them, and me as well. Nobody will be able to say how we sounded when we spoke. If they tell our old jokes, they won’t know whose they were.

That is what death means. We exist in the minds of other people, in thousands of memory clusters, and one by one those clusters fade and disappear. Some years from now, at a funeral with a slide show, only one person will be able to say who we were. Then no one will know.