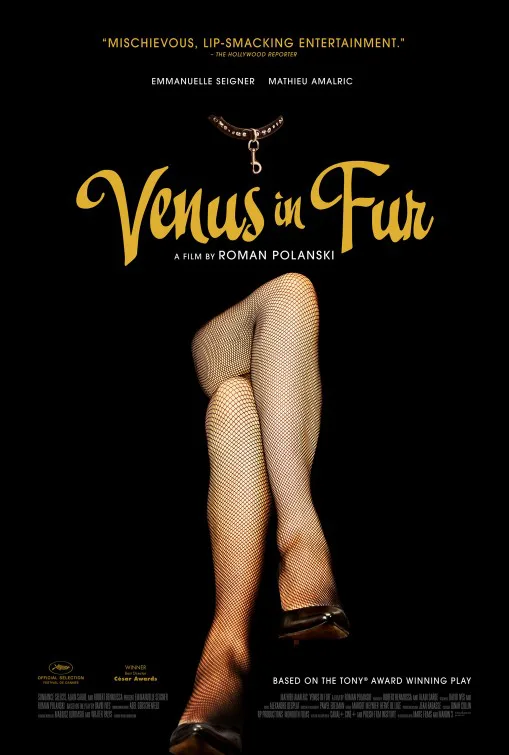

You’d be hard pressed to imagine a more seemingly perfect match of director and material than Roman Polanski and “Venus in Fur.” Too bad it isn’t a wickeder, subtler, more imaginative movie. Polanski’s second stage adaptation in a row (after “Carnage“) is a two-character play set almost entirely within a Paris theater, and mostly on a stage. A writer and director (Mathieu Amalric) auditions a late-arriving candidate (Emmanuelle Seigner) for the lead female role in his latest drama, and gets drawn into an elaborate role-playing game in which reality and fiction blur. As this brisk little movie unreels, the playwright and the performer act and talk their way through bits of the play, flirt with each other (mostly tactically but sometimes sincerely), work out motivation and dialogue problems, and discuss the story’s source material, the 1870 novel Venus in Furs by Austrian author Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, from which the term “masochism” springs.

Along the way we get to know their histories, their kinks, their fears and yearnings. Their relationship is about sex and art, but mostly it’s about power. In this play’s version of reality (and the film’s, which is simpatico) women are second-class citizens socially but trump men in their ability to inspire awe and cause misery. This is a sexist view, one that the play itself interrogates even as it’s dressing up its leading lady in tight-fitting leather and stiletto-heeled boots and setting her loose upon the movie’s hero, who never seems more boyishly alive than when he’s abasing himself. “Nothing is more sensuous than pain,” he tells her early on, searching her face for signs of recognition and delight. “Your ideal woman may be crueler than you care for,” she warns him. His eyes say: try me.

As the playwright Thomas Novachek, Amalric (a ringer for the young Polanski) gives his froggy voice and big eyes a workout. He’s perfectly cast as a pipsqueak whom artistic success has transformed into a smugly entitled star. The way Thomas casually bosses Seigner’s heroine Vanda Jordan around in the first few scenes—condescending to her, talking over her—will ring true to any woman who’s spent time in the worlds of theater or film. And the way the script eases in and out of different performance modes is intriguingly sly. You don’t always know if Thomas and Vanda are playing themselves or fictional protagonists Severin von Kushemski and Wanda. There are even a couple of places where Thomas and Vanda seem like constructs as well—human bracketing devices for a play within a play, and a play within a play within a play. Even though Vanda initially professes near-total ignorance of the play, the playwright and pretty much everything else, she keeps going off-book, as they say, yet still nailing her lines. How does she know the text so well? How does she know so much about the historical sources for the play, and about the playwright? How did she know to bring the leather? Who’s playing whom, and to what end?

Not many filmed plays have stuck closely to the physical constraints of their stage source yet still produced a thoroughly cinematic experience. My favorites include “What Happened Was…”, “12 Angry Men” and “Vanya on 42nd Street” (which, like “Venus in Fur,” segues into and out of “dramatic” situations without changes of costume, scenery or visual style). This is not one of the better examples of bare-bones adaptation. Polanski, one of the most visually inventive yet economical directors in film history, shoots everything in a boringly plain way here. The repetitive shot/reverse shot pattern seems more interested in capturing the acting than commenting on, amplifying or even presenting it.

Worse, Seigner, the director’s wife and frequent collaborator, just doesn’t rise to Amalric’s level. Her performance is as “big” as Amalric’s but not as exact or surprising. She tends to go for the most obvious, head-on approach in every scene, playing devious moments deviously, lusty scenes lustily, and so forth. The role needed a force of nature—an unpredictable and magnetic presence who could embody a description of the playwright’s aunt, a formative influence on his sexuality: “voluptuous and terrifying.” Seigner is the former, to be sure, but rarely the latter. When she puts a moment across, it’s because you’ve made up your mind to take the film’s word that she did it—or because Amalric is acting for both of them.

As a record of a particular performance of a particular play, “Venus in Fur” is all right. It’s of historic interest because Polanski directed it. But nothing about it immediately suggests that it was directed by a great artist, much less one whose own dark life (which included a statutory rape conviction, years of international wandering, a wife hacked to death by the Manson family, and family members claimed by the Holocaust) has been frankly explored in four decades’ worth of films which, taken together, amount to a constantly evolving stealth memoir. I understand intellectually why it spoke to him, but I wanted to feel it in my bones, like love or music. “Venus in Fur” never musters that level of dark magic. I would rather hear Polanski talk about why he was drawn to this material than watch his adaptation of it one more time.