The 1962 Cuban missile crisis was the closest we’ve come to a nuclear world war. Nikita Khrushchev installed Soviet missiles in Cuba, 90 miles from Florida and within striking distance of 80 million Americans. Kennedy told him to remove them, or else. As Soviet ships with more missiles moved toward Cuba, a U.S. naval blockade was set up to stop them. The world waited.

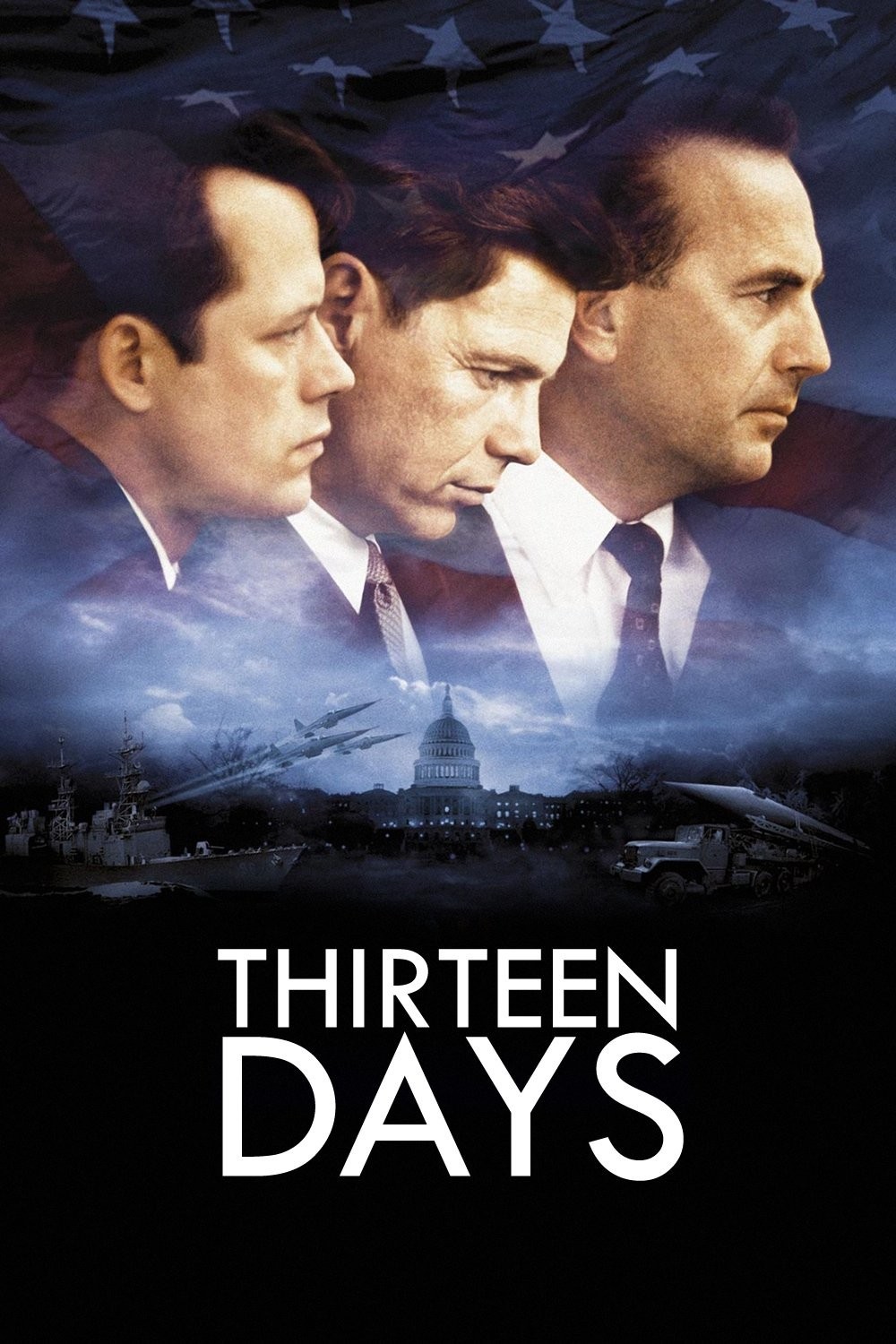

At the University of Illinois, I remember classes being suspended or ignored as we crowded around TV sets and the ships drew closer in the Atlantic. There was a real possibility that nuclear bombs might fall in the next hour. And then Walter Cronkite had the good news: The Soviets had turned back. Secretary of State Dean Rusk famously said, “We went eyeball to eyeball, and I think the other fellow just blinked.” The most controversial assertion of Roger Donaldson’s “Thirteen Days,” an intelligent new political thriller, is that the guys who blinked were not only the Soviets, but also America’s own military commanders–who backed down not from Soviet ships but from the White House. The Joint Chiefs of Staff and Air Force Gen. Curtis LeMay are portrayed as rabid hawks itching for a fight. It’s up to presidential adviser Kenny O’Donnell (Kevin Costner) and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara (Dylan Baker) to face down the top brass, who are portrayed as boys eager to play with nuclear toys. “This is a setup,” O’Donnell warns President John F. Kennedy (Bruce Greenwood). If fighting breaks out at a low level, say with Castro shooting at an American spy plane, “the chiefs will force us to start shooting.” This version of events, the viewer should be aware, may owe more to the mechanics of screenwriting than to the annals of history. In a movie where the enemy (Khrushchev) is never seen, living and breathing antagonists are a convenience on the screen, and when McNamara and a trigger-happy admiral get into a shouting match, it’s possible to forget they’re both supposed to be good guys. Yet the Cold War mentality did engender military paranoia, generals like LeMay were eager to blast the commies, and Kennedy was seen by his detractors as a little soft.

“Kennedy’s father was one of the architects of Munich,” grumbles Dean Acheson, Truman’s secretary of state and an architect of the Cold War. “Let’s hope appeasement doesn’t run in the family.” My own feeling is that serious students of the missile crisis will not go to this movie for additional scholarship, and that for the general public it will play–like Oliver Stone’s “JFK“–as a parable: Things might not have happened exactly like this, but it sure did feel like they did. I am not even much bothered by the decision to tell the story through the eyes of O’Donnell, who according to Kennedy scholars can barely be heard on White House tapes made during the crisis, and doesn’t figure significantly in most histories of the event. He functions in the movie as a useful fly on the wall, a man free to be where the president isn’t and think thoughts the president can’t. (Full disclosure: O’Donnell’s son Kevin, the Earthlink millionaire, is an investor in the company of “Thirteen Days” producer Armyan Bernstein.) Costner plays O’Donnell as a White House jack-of-all-trades, a close adviser whose office adjoins the Oval Office. He has deep roots with the Kennedys. He was Bobby’s roommate at Harvard and Jack’s campaign manager, he is an utterly loyal confidante, and in the movie he helps save civilization by sometimes taking matters into his own hands. When the Joint Chiefs are itching for an excuse to fight, he urges one pilot to “look through this thing to the other side”–code for asking him to lie to his superiors rather than trigger a war.

The movie’s taut, flat style is appropriate for a story that is more about facts and speculation than about action. Kennedy and his advisers study high-altitude photos and intelligence reports, and wonder if Khrushchev’s word can be trusted. Everything depends on what they decide. The movie shows men in unknotted ties and shirt-sleeves, grasping coffee cups or whiskey glasses and trying to sound rational while they are at some level terrified. What the Kennedy team realizes, and hopes the other side realizes, is that the real danger is that someone will strike first out of fear of striking second.

The movie cuts to military scenes–air bases, ships at sea–but only for information, not for scenes that will settle the plot. In the White House, operatives like O’Donnell make quiet calls to their families, aware they may be saying goodbye forever, that the “evacuation plans” are meaningless except as morale-boosters. As Kennedy, Bruce Greenwood is vaguely a look-alike and sound-alike, but like Anthony Hopkins in “Nixon,” he gradually takes on the persona of the character, and we believe him. Steven Culp makes a good Bobby Kennedy, sharp-edged and protective of his brother, and Dylan Baker’s resemblance to McNamara is uncanny.

I call the movie a thriller, even though the outcome is known, because it plays like one: We may know that the world doesn’t end, but the players in this drama don’t, and it is easy to identify with them. They have so much more power than knowledge, and their hunches and guesses may be more useful than war game theories. Certainly past experience is not a guide, because no war will have started or ended like this one.

Donaldson and Costner have worked together before, on “No Way Out” (1987), about a naval officer assigned to the Pentagon who stumbles into a criminal cover-up. That one was a more traditional thriller, with sex and murders; this time they find almost equal suspense in what’s essentially a deadly chess game. In the long run, national defense consists of not blowing everything up in the name of national defense. Suppose nobody had blinked in 1962, and missiles had been fired. Today we would be missing most of the people of Cuba, Russia and the U.S. Eastern seaboard, and there’d be a lot of poison in the air. That would be our victory. Yes, Khrushchev was reckless to put the missiles in Cuba, and Kennedy was right to want them out. But it’s a good thing somebody blinked.