It’s good to spend some time alone. It allows you to think uninterrupted about the big questions. Why am I here? What are the things in life I value? What would I be capable of if pushed to extremes? Why are dogs always so happy?

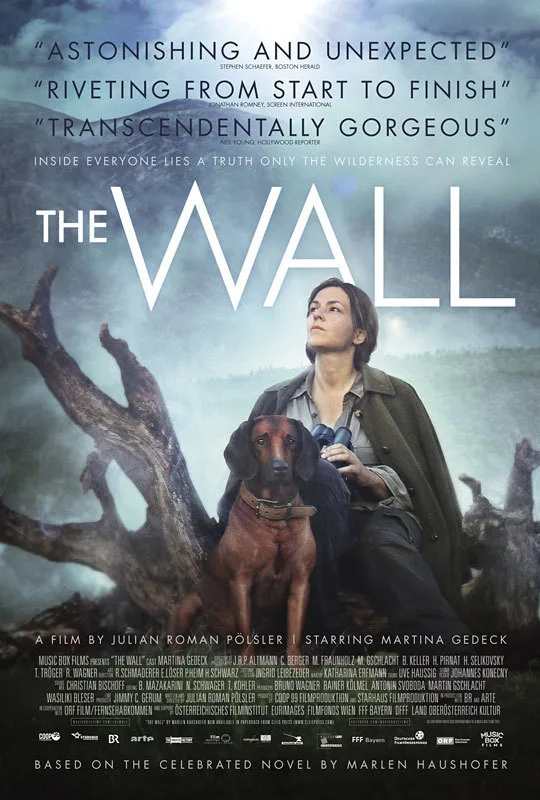

The nameless main character (Martina Gedeck) in “The Wall” has more time alone than anyone would wish. She’s visiting the remote hunting lodge of two old friends. They decide to drive back into town for the evening, but she stays behind. They do not return. The next morning, concerned that they have still not come back, she begins walking down the road to the village, and is stopped by an invisible wall. She’s trapped. And no one is coming to save her. She can see people beyond the wall, and though the natural world continues to move and grow and change, they are frozen in place, like mannequins. She is, so far as she can tell, utterly alone.

The premise, drawn from an acclaimed 1963 novel by Marlen Haushofer, will inevitably call to mind Stephen King‘s “Under the Dome,” but that comparison won’t get you very far in explaining what “The Wall” is about. King’s book and the TV miniseries based on it are about how a community interacts in isolation when catastrophe strikes, and the normal rules and systems are stripped away. “The Wall” is about the individual. Does a person remain human if they are totally without community?

The woman at first tries to test the boundaries, to find out whether she can somehow find a way out of the smaller world she now inhabits. The wall seems to enclose a very large area, but she cannot explore its far reaches without climbing out of her valley. Gradually, as the days pass, she adapts to her new reality, harvesting mushrooms and fruit from the forest, learning to hunt, planting a crop of potatoes from the supplies in the pantry.

And she thinks. She wonders if this new person she is becoming is her true self. She considers whether it is worth going on when there is no hope of ever seeing another human being again. She ponders the relationship of humans and dogs.

Ah, the dog. I’ve said that she is alone, but that’s only if you count people. In fact, she has her friends’ dog, and eventually a pregnant cow she finds wandering in the valley, and a cat, which soon has a kitten (suspicious, you might think, that two of the animals she finds are pregnant). She makes a little family out of these animals.

All of this we are told in the omnipresent voiceover that is both crucial and a weakness. Since this is a movie about a person thinking, we need the narration (which takes the form of a “report” she writes at some unspecified point in the future, still alone behind that wall). But there are times when you might wish, as I did, that she would just stop talking and let you contemplate the eerie stillness of her existence.

Very little happens in this movie that we might call a plot. This isn’t about her heroic discovery of an escape route. She doesn’t have to battle dangerous wild animals or overcome the kind of overblown adversity of a wilderness adventure in the Jack London tradition.

Instead, the movie offers a study of a person in isolation, left to do the mundane tasks of survival (which are rarely as exciting as what you find in survival movies like “The Grey“). It’s more like “Robinson Crusoe,” in the long section before Crusoe meets Friday. There are incidents, like her first successful hunt, but there is not the dramatic build we get from most movies, so driven by plot that they often feel like engines designed only to get us to that satisfactory moment when the heroes have achieved their goals.

Without the usual engine of plot, without the confidence that cause will lead to effect and it will all build to a satisfying climax and resolution, we are left adrift, rather like the woman, to try to make meaning out of what we are given. Does it matter that the animals are pregnant? If the wall is a metaphor for something, what is that something? Is the woman right when she describes herself as transforming into a new kind of thing not human at all, or is she losing her sanity? Why is a film about tragic, epic isolation so filled with stunningly gorgeous images, from the interiors that look like perfectly lit still-lifes by a Dutch master to the breathtaking shots of the mountains and the high pastures? This is a movie of questions. Perhaps too many questions.