French/Japanese fable “The Red Turtle” is one of those rare animated movies that transports you to a different setting without demanding that you focus on narrative or character development. Instead, viewers are encouraged to fall in love with an environment, specifically a small tropical island on which a nondescript, mute castaway inexplicably finds himself shipwrecked. This focus on setting over narrative is crucial since “The Red Turtle” follows the normalization of one man’s romance with nature. Because this is a fable, the above-mentioned romance is quite literal: our nameless castaway falls in love with a shapeshifting turtle that transforms into a beautiful naked woman. He also inevitably stops trying to escape his surroundings, and starts to build a home on the island.

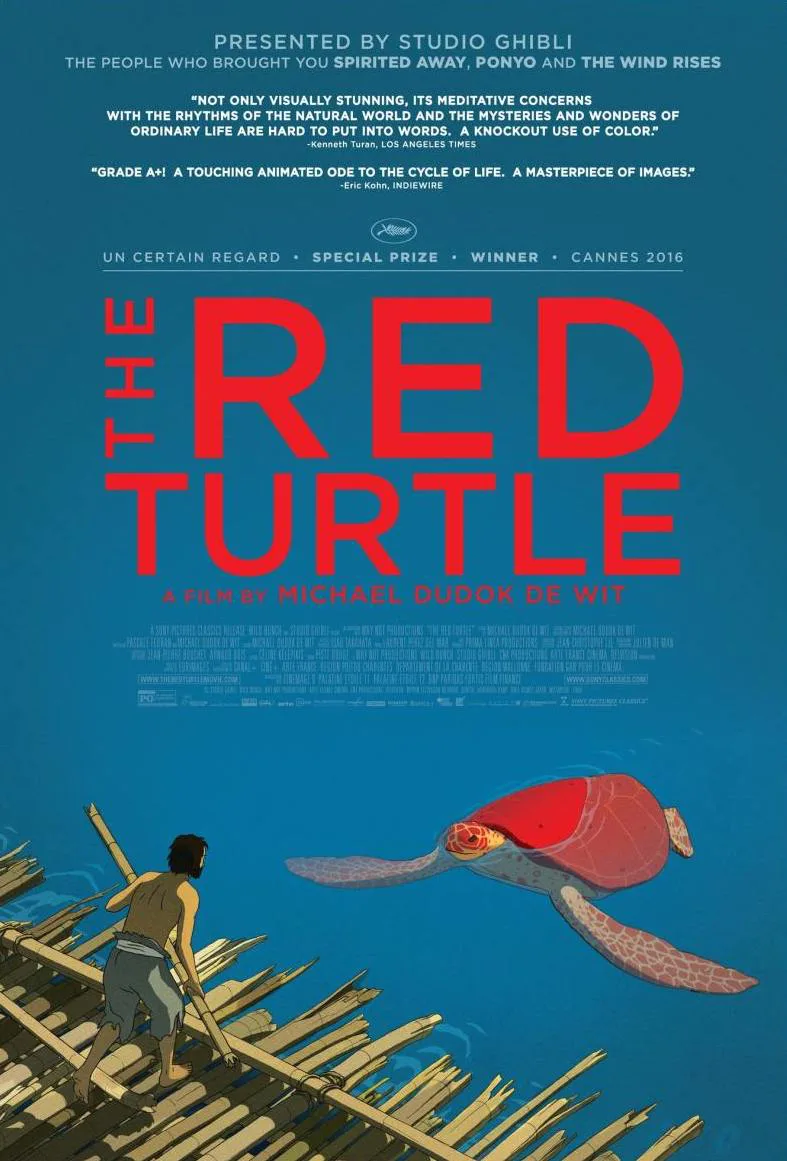

That may sound like a major spoiler, but “The Red Turtle” is a mood piece for children, so plot twists don’t really matter. The film, which was produced by Japanese animation studio Studio Ghibli, has an intricately-articulated, and confidently-utilized hand-drawn style that lures you in, and makes you want to accept such a blunt, bleeding-heart metaphor for ecological awareness.

“The Red Turtle” begins as a “Robinson Crusoe”-style man vs. nature-style narrative, a mode that viewers should be comfortable and/or familiar with. You know this story: a man arrives on an island and must, through sheer force of conviction and ingenuity, rescue himself by creating shelter, foraging for food, and building a raft to escape. The main difference between this type of story and the one that “The Red Turtle” eventually becomes is that there’s always something that’s entreating or trying to catch the viewer’s eye, whether it’s blessedly un-anthropomorophosized crabs, or a forest of gently swaying bamboo shoots. There is subsequently a subtle tension at play at the beginning of the film: the island’s personality asserts itself even as we are encouraged to get caught up in our hero’s captivating routine of building a raft, trying (and repeatedly failing) to escape, daydreaming while gazing at the moon, and then inevitably repeating this makeshift procedure.

That tension comes to a head once the title character appears. She is, at first, an invisible, seemingly adversarial presence that stops the film’s castaway protagonist from breaking away from his island prison. She destroys his raft, though at first it’s hard to tell what’s happening since she retreats from view every time he tries to catch a glimpse of her.

Still, he is as stubborn as she is, so the castaway tries to build another raft, over and over repeating his process. But eventually, he realizes that there’s an observable presence that’s out to get him. We join the castaway as he learns that A) he’s being barred from leaving by a physical presence B) that presence is not out to get him and ultimately C) that presence is beautiful.

Getting from A to B is probably not nearly as difficult a leap in logic for viewers as getting from B to C. But co-writer/director Michael Dudok de Wit gets viewers to suspend their disbelief by consistently drawing our attention to his film’s natural surroundings. This is an enchanted environment, though not in the way you might expect based on Disney cartoons like “The Little Mermaid” or “Peter Pan.” There are some cute animal inhabitants for us to relate to, like the above-mentioned crabs. But for the most part, we are asked to relate to the world through lush details. We experience the overwhelming force of a sudden rainstorm through sound design: rain water pelting bamboo shoots, wind tearing up leaves and tall grass, and normally still waters rippling uncontrollably. In this way, we adjust to the pace of island life by sharing in the castaway’s thrilling process of discovery.

So when “The Red Turtle” eventually becomes a story about a man, a (magical reptile-)woman, and their life together, it doesn’t feel strange. Dudok de Wit successfully teaches viewers to see his two main characters as extensions of the world they inhabit, leading us to see their evolving relationship as an extension of their deepening connection. Or, to put it another way: these two characters care about each other because they eventually realize that they not only aren’t enemies, but are two people who happen to share the same world. There’s something amazing about that kind of bond, something that I absolutely did not expect from a children’s film: characters growing to like each other and solve problems together based on a mutual appreciation of their surroundings. “The Red Turtle” also draws viewers in by immersing us in a fully-realized microcosm. Dudok de Wit, co-writer Pascale Ferran, and an accomplished battalion of animators have created a thoroughly disarming fairy tale, one that initially appears familiar, but eventually reveals itself to be something new, and altogether unexpected.