If it were possible to splice the DNA of William Faulkner and John Cassavetes, the resulting progeny might produce a film like Roberto Minervini’s “The Other Side,” an immersive, almost harrowingly naturalistic plunge into the lives of marginal Louisianans obsessed with guns, drugs and belligerent resentments.

The problem with the above description, though, is that Faulkner and Cassavetes dealt in the realm of the fictional. “The Other Side” has been described in some reviews as a documentary. Yet Minervini—an Italian now based in the U.S.—clearly operates in a netherworld between fiction and reality.

A better comparison—in terms of method, if not tone—might be films like “Trash” and “Heat” that Paul Morrissey made for Andy Warhol, elaborating on a deadpan approach the artist had developed in his earlier films. In the Warhol-Morrissey features, the camera mainly sat back and observed the assembled junkies, drag queens and hustlers from a neutral distance. Minervini, on the other hand, uses cinematographer Diego Romero’s gorgeously underlit, smoothly hand-held camerawork to create an effect that, because it is more intimate and beautifully crafted, also feels more like that of a fictional film.

As in the Warhol-Morrissey films, what we see here aren’t actors acting but real-life characters interacting, in a context that gives their personalities and relationships a loose narrative frame. As in those earlier films too, there’s lots of casual drug use, nudity and some sex. It’s worth stressing at the outset, though, that these elements do not seem included for their prurient or entertainment appeal; the filmmaker’s purposes, clearly, might more accurately be described as exactingly anthropological.

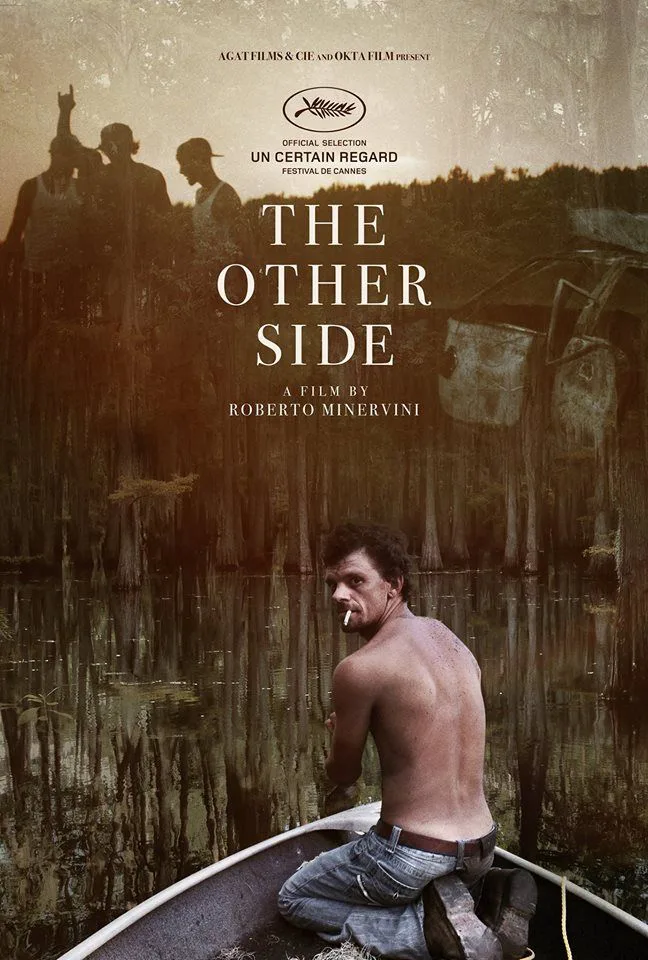

The film opens with men in hunting gear trailing through a wooded landscape. Then we see 30-ish Mark (Mark Kelley) lying beside a country road in the early morning light, naked, evidently either drunk or stoned. He gets up and staggers down the road, and later meets his corpulent, disheveled girlfriend Lisa (Lisa Allen) and smokes crack with her. The two have an easygoing banter that bespeaks both respect and jokey familiarity.

Mark is a grizzled, tattooed guy, but not without a certain rugged charm and animal vitality. He looks a bit like Mark Ruffalo might look if the actor had a meth habit. Though much of the time he’s doing nothing but laying around, getting messed up or engaging in nude frolics with Lisa—he’s also the first of many folks here to launch into a venomous anti-Obama tirade—we also see him doing some honest work in day jobs and trying to help out his family members, including a sister, niece, mother and grandmother.

It emerges that Mark was convicted of a felony but has been able to postpone serving his prison time. His mother was recently diagnosed with cancer; when she dies, he tells Lisa, he plans to get drunk every day and then go serve his sentence in order to clean himself up. This plan and the emotions sparking it hint at a kind of dramatic shape and logic that the film, however, largely eschews in order just to follow the characters on their rounds, which include, for example, visiting a strip club where a very pregnant woman shoots up heroin backstage, then performs lewd dances for loud rowdies out front.

These characters’ lives recall recent sociological studies on the changes lower-class whites have experienced since the 1960s. Prior to that decade, traditional morality and religion held sway; hippies, dope and amorality were the enemy. But after the 1960s’ liberalizing winds swept through, the old standards fell away and nothing equally sustaining replaced then. Jesus went out, meth came in.

If Minervini had been out to convert such realities into stark tragedy, he could have built up to Mark going into a nihilistic freefall or committing a despairing crime. Instead, very unconventionally, he simply drifts away from Mark and begins focusing on a group of camo-clad militia types, who delight in shooting off their weapons, cursing Obama and envisioning a national disaster ahead. Their tawdry, downscale world is one of Confederate flags, ammo boxes and John Wayne posters.

It’s far easier to describe the film’s surface and thematic elements than to precisely convey Minervini’s perspective and tone. As a native Southerner often skeptical of the way the region is portrayed in movies, especially ones made by outsiders, I am largely persuaded that Minervini’s work is sincere and perceptive, and that it adds something new and valuable to the cinematic literature on the region.

He doesn’t indulge in caricature or sensationalism, any more than Faulkner did, even if some of the people he observes exist on the edge of grotesquerie. He sympathizes with them while keeping an observant distance and trying to capture the exact textures of their lives, much as Cassavetes did. His previous Texas Trilogy—“The Passage,” “Low Tide” and “Stop the Pounding Heart”—took a similarly naturalistic, if more lyrical, approach to other, less troubled Southern communities. “The Other Side” is a rougher ride, but one that further demonstrates his skills and acuity as an observer of Southern cultures.