“To die – to sleep. To sleep – perchance to dream: ay, there’s the rub! For in that sleep of death what dreams may come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil Must give us pause.” – Hamlet, Act III, scene 1

What is so striking is the similarity of the stories. People describe lying in bed, awake, unable to move. There is a tingling sensation, like static, like nerve endings shorting out from overuse. People describe a feeling that something is approaching, from behind them, or towards them. Along with that approach comes an overwhelming sense of evil. Dark amorphous shadow figures appear, somewhat human-like, leaning over the person lying in bed, appearing at the door frame. Sometimes the dark figure wears a hat. Something terrible is going to happen and the person is unable to move or to react. This is the experience commonly known as “sleep paralysis” and is the subject of Rodney Ascher’s engaging horror-film-like documentary, “The Nightmare.”

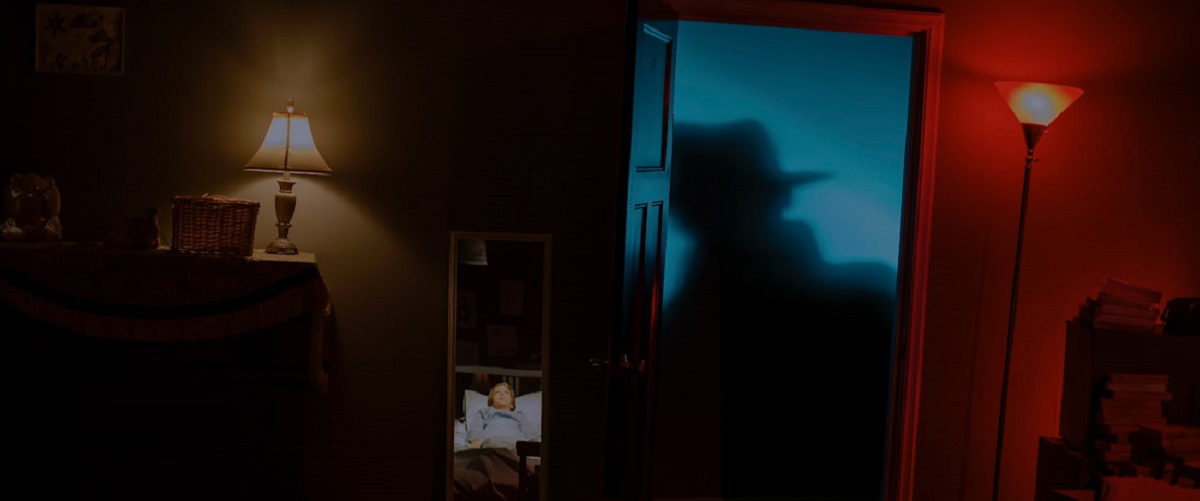

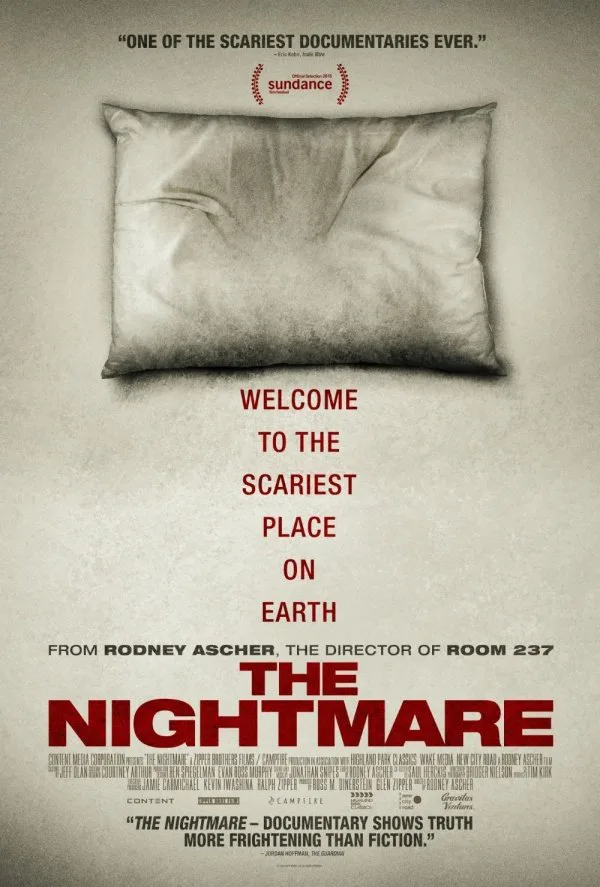

Ascher does not focus on the many theories as to what causes sleep paralysis (stress, interrupted REM sleep). The theories come up, but only through the voices of those who experience the phenomenon. There are no official talking heads from the scientific community, showing us diagrams of sleep cycles or brain waves. Instead, “The Nightmare” is filled with people from different regions of the country (and the world) telling their stories, accompanied by creepy re-enactments of their sleep paralysis nightmares. Using a horror-film color palette (the shadows are “Lost Highway“-thick) and horror-film camera techniques, Ascher plunges us into the actual visions that sleep paralysis creates: the moving silhouette figures, the darkness, the static. The sense of terror is palpable.

The people telling their stories are filmed in their own homes, but with off-kilter angles, and extremely low lighting, making their surroundings look grim and dark. The shadows encroach on all sides. One guy stops telling his story and peers behind his shoulder, freaked out for a second. With one interview subject, Ascher has placed the camera in the next room, peeking through the doorway, an abyss of blackness in between us and the subject. The overall effect gives the sense of a sleep disorder so overpowering that it has changed people’s lives forever. One guy admits that one vision was so frightening that “I immediately stopped being an atheist.” Some have come to the conclusion that the terror will eventually get so intense that they will die from it. They all look haunted and obsessed. They try to draw pictures of what they saw, scribbling images out when it doesn’t look right. They are not believed when they tell their stories. These are not “bad dreams,” they are something else entirely. The quotes accumulate throughout the film, bringing with them a sense of dread all their own: “I thought I was having a stroke.” “I felt a presence next to me trying to take my soul out.” “And that is when the Shadow Man came towards me.” “If I could describe what Death would feel like – it’s icy-cold, dark, evil, and it’s watching me.”

Many of these people have been “visited” (they describe it as such) since they were babies, and for a lot of them a sleep paralysis nightmare is their very first memory. One guy describes two figures made up of television static leaning over his crib, grinning maniacally, reaching in for him. People suffer in isolation, thinking they are the only ones. When the Internet started to rise in importance, one woman decided to see what would happen if she put “shadow man” and “nightmare” into a Search box, and suddenly she found message boards with people sharing similar stories, and also a label: “Sleep Paralysis.” She felt exultant, crying to the camera, “It’s a thing!” Others found similar moments of connection and recognition, sometimes from very unlikely places. A couple of people describe seeing “Nightmare on Elm Street” for the first time and feeling like it was a documentary as opposed to a horror-film. Freddy Krueger was the shadow man they saw in their dreams, and he wore a hat, too, as the visions often do. One guy describes seeing “Communion,” with Christopher Walken, and recognizing the faces of the aliens as being similar to the barely-perceived faces on the figures he saw at night. He wondered if a lot of alien abduction stories were actually sleep paralysis. “Insidious,” too, brought flashes of recognition: That’s what it is like!

Once you start digging deeper, as all of these people do (they become experts in their own condition), you see evidence of “sleep paralysis” in all cultures, throughout history. It shows up in myths and folk tales. It has different names but it’s the same phenomenon. There’s a 1781 painting by Henry Fusili called “Nightmare”: a woman lies prone across a bed in a white gown, her head flopped over to the side. Crouching on her torso is a small gargoyle-like creature, an incubus, staring directly at the viewer with a malevolent blankness. As the incubus suggests, there is a sexual element to some of these nightmares. One woman describes being raped by a shadow figure who crawled on top of her in bed, and she was unable to move or resist. Fusili’s painting is phantasmagorical, but to those in the documentary, it is an accurate depiction of their reality.

Each person interviewed has struggled to control their sleep paralysis. Is the condition psychological or physiological? Many of the people interviewed cannot believe or accept that it is a purely physical phenomenon. Everyone describes that there is a spiritual element to the experience, a tug-of-war between Good and Evil. One woman claims she was cured by whispering the word “Jesus” repeatedly during a sleep paralysis attack. She was not a religious person in the slightest, but in that moment she realized that the word “Jesus” had power. Since then, her sleep paralysis stopped. One guy slept with the television on and that seemed to help for a time. But then it stopped working, so he added another television to the mix, until eventually he had about 10 televisions in his bedroom. “It made me look like a crazy person,” he said.

Ascher’s 2013 documentary “Room 237” plunged us into the world of those obsessed with Stanley Kubrick‘s “The Shining.” One guy was convinced that Stanley Kubrick helped fake the moon landing footage, and “The Shining” was Kubrick’s subliminal admission of that. One woman was obsessed with the architecture of The Overlook Hotel, making her own floor plans. “The Nightmare” is similarly structured, in that the voices of those telling the stories dominate. There is no omniscient narrator, telling us what it means, or providing us with a larger perspective. “The Nightmare” is more effective than the esoteric “Room 237” because it represents a full immersion into a common human experience. The re-enactments are superb. While there are similarities in the stories, each person has a different version of the same experience, and Ascher and his production team has worked beautifully to help bring that to life. Bridger Nielson’s cinematography is moody and gloomy, inky-black shadows punctuated by fragile colored night-lights, blue-lit doorframes, shadowy figures moving through the blackness, across the foreground, silhouetted in doorways. One person says, memorably, “All the darkness looks alive.” It’s a terrible thought. Ascher himself has experienced sleep paralysis, and was struck, in his research, by how the stories all sounded the same. What is unique to the sufferer is actually a common experience. In “The Nightmare,” he leads us into that other-world of terror where the darkness is alive. And it moves on its own. And it’s coming to get you.