Wannabe mystery authors can learn how to make better detective fiction by studying what the makers of gory period mystery “The Limehouse Golem” do wrong. Director Juan Carlos Medina and screenwriter Jane Goldman, the latter of whom based her scenario on Peter Ackroyd’s novel, have essentially made an upscale installment of “Masterpiece Mystery,” complete with a Victorian-era setting, an attractive high-concept pair of lead protagonists—a rumored-to-be gay sleuth, and an actress who has been accused of poisoning her playwright husband—and an unchallenging narrative centered on a series of murders in pre-Jack the Ripper-era London. Had Goldman’s characters possessed any psychological depth, they might have been compelling reflections of our modern lust for true crime sensationalism and/or society’s still-prevalent mistrust of genre fiction that is even superficially concerned with the empowerment of women, either through direct representation and/or authorship. Instead, “The Limehouse Golem” only reflects its creators’ lack of imagination. Medina and Goldman invest so much time in (poorly) misleading audiences that they say nothing memorable about the past, or why it matters to today’s audience.

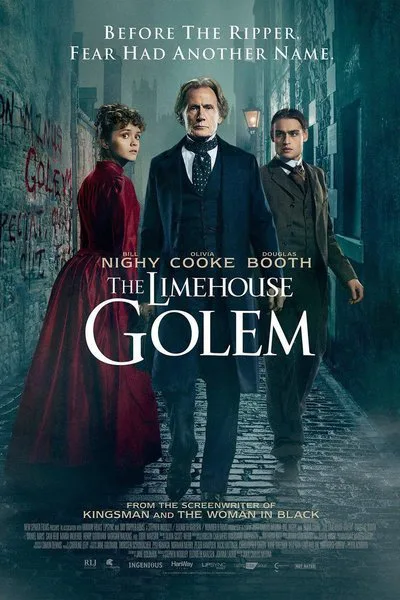

Our story begins well enough: Inspector John Kildare (Bill Nighy) must solve a high-profile series of deaths in London’s seedy Limehouse district. John, an untested cop who is presumed to not be “the marrying kind,” knows that if he fails to crack the case, his department will not back him up. Still, he becomes obsessed with the “Limehouse Golem” slayings, and its initially tangential connection with the case of accused murderess Lizzie Cree (Olivia Cooke), an aspiring theatrical star who is accused of offing husband/playwright John Cree (Sam Reid). John patiently listens to Lizzie’s testimony through a series of lengthy, and largely uninspired flashbacks, and struggles to intuitively connect her dull rise-to-fame story with a handful of seemingly disparate killings.

John’s interest in Lizzie is essentially unclear since we are led to believe that he has no romantic feelings for her. We know nothing about John other than his perceived queer identity because Goldman never addresses that rumor, nor does she flesh out John’s character in any other meaningful way. Even John’s partner, schlubby, but down-to-Earth detective George Flood (Daniel Mays), doesn’t understand why John keeps returning to Lizzie’s prison cell to listen to her explain why she wanted to star in her husband’s penny-dreadful-inspired musical reviews, all of which rely implicitly on the exploitation of sex, and violence. John’s investigation should, in this sense, reveal something about his character, or just his preconceptions of who Lizzie is.

But the makers of “The Limehouse Golem” aren’t concerned with character development, or period detail. Instead, they myopically focus on John’s need to rule out suspects, including, of all historical figures, Karl Marx (a joylessly campy Henry Goodman, who thankfully is only in one interminable scene). Johns runs around London, interrogating secondary characters whose defining flaws and eccentricities immediately rule them out as viable psychopaths. After all, the first unspoken rule of cheapjack murder-mysteries is that a suspect is no longer worth considering once they become such an obvious target that our heroes suspect them. Unless the end credits are about to roll, anybody who is believed to be suspicious should be presumed innocent. This is the “whodunnit as magic trick” theory of crime fiction: misdirection is more important than anything else. That approach is unfortunately a major shortcoming in “The Limehouse Golem” since the real killer can be easily identified if viewers consider which major character is the only one that Goldman and Medina actively demand that we trust and root for. Once you eliminate the predictable, whoever remains, no matter how trite, must be the culprit.

Medina’s general preference for thrice warmed-over representations of 19th century London’s streets and interiors also leave much to be desired. He tends to rely so much on pool-table green and silvery-blue camera filters that even Nighy’s stately silhouette looks ordinary. The streets that John stalks also look too familiar. Drunk proles, prim socialites, and undefined women of the night are everywhere, but nobody worth knowing beyond these costume drama cliches. It’s no wonder that Goldman’s tepid story can’t shoulder the weight of an entire film: there’s nothing else here to latch on to, not even Nighy’s normally delightful scenery-chewing. Medina, a neophyte director, doesn’t seem to know how to translate his interest in Goldman and Ackroyd’s source material into a compelling, stylish thriller. In its present state, “The Limehouse Golem” is as inessential as an inferior serial from Jeremy Brett’s otherwise sterling run of 1980s Sherlock Holmes TV adaptations. It’s adequate as comfort food, but fails as anything else.