Now 82, director Jan Troell is arguably the last surviving Old Master of Swedish cinema. His movies (the first to gain international prominence was his 1971 “The Emigrants“) are beautifully shot and painstakingly detailed stories, often period ones, chronicling the lives of characters struggling with difficult circumstances and environments. He is not as concerned with interior anxieties as was the man most of us consider Swedish cinema’s grandmaster, Ingmar Bergman (although Troell frequently works with actors we tend to associate with Bergman, such as Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann). On the other hand, Troell is not nearly as dynamic a storyteller as Bergman. While even the most existentially knotty of Bergman’s films tries to grab the viewer by the back of the neck and carry him/her on a wave of narrative momentum, Troell’s movies are more insinuating. It is likely not an accident that his new movie, “The Last Sentence,” opens with images of water moving slowly in a stream, and then the nib of a pen being dipped in ink, and writing out a word, then another, in a calm flow.

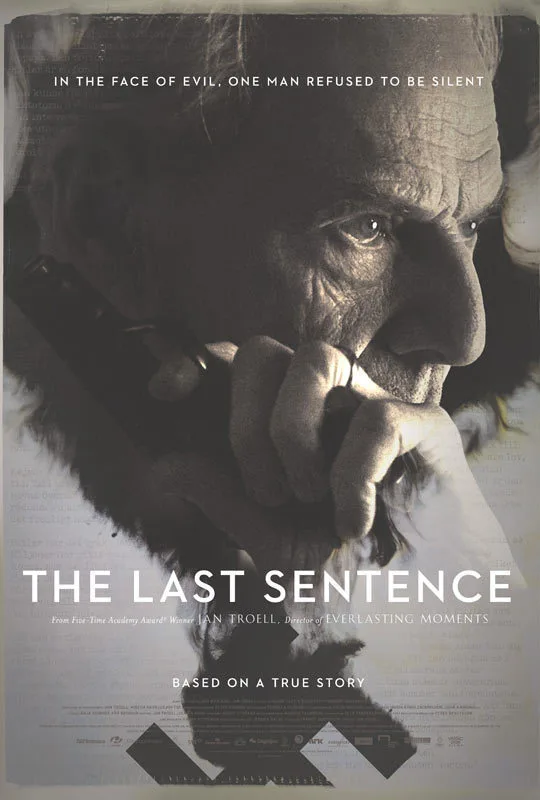

The movie’s black-and-white images—shot, for the first time in Troell’s career, digitally—are gorgeous, by the way. Troell’s movies always look magnificent. The words being written in the movie’s opening are from the pen of one Torgny Segerstedt, a real-life figure from whose biography Troell and Klaus Rifbjerg adapted the movie’s story. Already an older man as the movie opens in 1933, Segerstedt is an academic theologian and newspaper editor appalled by what he sees happening in Germany, and moved to comment on it. The veteran Swedish actor Jesper Christensen has a pronounced resemblance to the distinguished-looking, white-haired real-life Segerstedt, and Christensen invests the character with a gravitas one would expect of such a crusader. At the movie’s beginning, Segerstedt’s anti-Hitler rhetoric is perceived by his friends as quixotic; “All that’s missing is the horse,” one crony snarks; “He has the lance,” another replies.

But the picture is not just about Segerstedt’s lonely attempts to wake up his people. The man has a complicated home life, conflicted about his wife, and not fully satisfied with his mistress, either. A complicating factor is that his mistress is the wife of his best friend. To sort things out, Segerstedt has intense conversations with his late mother (the movie is not without its Bergmanesque touches, as we see). “The lack of love will lead to death” he muses, but the man seems incapable of giving love. Troell makes Segerstedt easy to admire but very hard to like, which is of course part of the movie’s point. As events bear out Segerstedt’s conviction that Hitler is a monster, the politicians and power brokers of his country grow more skittish, with the country’s Prime Minister complaining to Segerstedt, “Let me put it plainly: you endanger national security with your writing.”

“Will there be a war?” one character asks Segerstedt as the Nazi threat grows. “There IS war,” Segerstedt replies, calmly. One of the refreshing things about this character is how he makes a big noise while never actually raising his voice. While the movie may be too concerned with immediate Swedish concerns to make what American viewers would consider a “universal” statement, “The Last Sentence” nevertheless is a remarkably full-bodied and frank character study that illuminates the old saw about the political being personal in a genuinely unusual way.