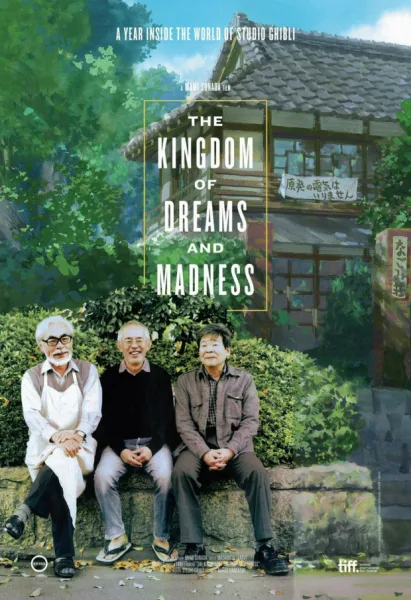

For “The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness,” director Mami Sunada was allowed remarkable access to one of the most important artistic enterprises of the last half-century, Studio Ghibli, at a unique point in its existence. News about the shuttering of the company that has given the world masterpieces like “My Neighbor Totoro” and “Spirited Away” reverberated throughout the animation community and beyond earlier this year. And there’s a sense in “Kingdom” that this is an elegy of sorts, a goodbye to an era of remarkable creative resonance. The cinematic visions that emerged from the drawing tables of this relatively nondescript building have influenced countless creative voices, and will continue to do so for the rest of time. To say I’m a Ghibli fan would be something of an understatement (my “Totoro” iPhone case had to be internationally ordered, for the record), and so “Kingdom” naturally speaks to my interests. If you’re not enraptured with the work of Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata and the rest of the artists at Ghibli, it may not be precisely what you’re looking for, but Sanada captures something poetic about art and creativity that could speak to anyone, animation fan or otherwise.

Having said that, it’s very helpful to have seen “The Wind Rises” and “The Tale of the Princess Kaguya,” the two most recent Ghibli films, and the two pieces being worked on for the year Sanada had access to the studio. Just the very idea that two such massive productions from two masters of the form were being produced simultaneously seems to cause ulcers in several producers involved. And yet Miyazaki’s process has been the same for decades. He works from 11am-9pm every day, on the dot. He doesn’t write scripts, he writes storyboards, and his assistants begin production from those drawings before he’s done, unsure of how the film will end. Miyazaki is very open with his process, opening his studio and home to Sanada, and philosophizing on art and humanity in ways that feel like someone coming to terms with a life’s work. He speaks candidly about how he makes films for others, most notably the people at Ghibli, and yet there’s something so deeply personal about “The Wind Rises” that it’s the first film that makes him cry after its premiere screening. He shares the “beautiful but cursed dreams” of its protagonist.

“The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness” contains surprisingly little actual film footage. There are more shots of Miyazaki’s cat than his films. We see bits and pieces of “Wind Rises” as it’s being assembled, but this is more a “year in the life” documentary than a history of the studio, although there are bits and pieces of the latter. Sanada’s film is at its best when the director conveys the realization that this is a studio and creative voice at the very least in a transitional period and arguably in its twilight phase. The music, the tone, the subject matter of the two films, Miyazaki’s candid self-reflection—it all combines to paint a portrait of something beautiful that’s coming to an end. At nearly two hours, Sanada hits a few of these beats a bit too many times, even for this fan, and the film bizarrely feels like it’s ending around the 90-minute mark, complete with a production-finishing montage, only to go on for another half-hour. It’s a fascinating look into a creative process that has been essential to the history of animation, but it could have been tighter as a documentary.

There’s an amazing passage in which Miyazaki receives a letter from a man who received assistance from Miyazaki’s father after the war. The production of “The Wind Rises” inspired the man to write Miyazaki, and the director points out how the event “Probably shaped the way this man looked at the world.” Reality influenced art which then reflected back on reality. The truth is that Miyazaki and the people at Studio Ghibli have been shaping the way we look at the world for years, and will continue to do so long after the Kingdom has closed.