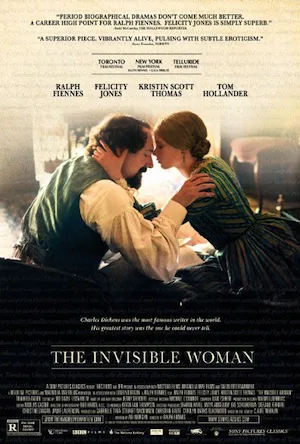

More mood piece than melodrama, Ralph Fiennes’ “The Invisible Woman” brings extraordinary delicacy and cinematic intelligence to the true story of a love affair that Charles Dickens kept secret from the time he met then 18-year-old Nelly Ternan in 1857 until his death in 1870. Told with a finely calibrated poetic obliqueness that draws the viewer into the relationship’s gradual unfolding, the film represents a formidable achievement for Fiennes as both actor and director.

Told in flashback, the drama opens years after the author’s death, when Nelly (Felicity Jones) has emerged from his shadow, reinvented herself as a lady, and married a schoolmaster (Tom Burke). As her husband’s pupils prepare to perform one of Dickens’ plays, an elderly local pastor and Dickens’ devotee (John Kavanagh) probes the “friendship” she is said to have enjoyed with the famous writer, which unleashes the flood of memories that comprises the story proper.

As the film reminds us throughout, Dickens (Fiennes) was a man not only of the printed page but of the stage as well, a buoyant performer and crafter of occasional theatrical entertainments. That’s how he meets Nelly, an actress in a family troupe that includes her mother (Kristen Scott Thomas) and two older sisters (Perdita Weeks, Amada Hale). When he engages them for one of his shows, it’s clear that the outgoing Dickens likes all four Ternan ladies but takes a particular shine to the almost Botticellian beauty of Nelly, who responds to his very polite attentions with a mixture of shyness and curiosity.

At this point in his life, Dickens is an enormous literary celebrity, a point made vividly in a scene where he attends the Doncaster horse races and is mobbed like a latter-day rock star. Happy in the limelight and within his prodigious work regimen, he nonetheless is dissatisfied in his marriage to Catherine Dickens (Joanna Scanlan), a large and dowdy matron who has borne him ten children but provides no intellectual companionship.

Given the strictures of Victorian morality, the romantic possibilities between Dickens and Nelly are not quick to blossom. At first they are never alone and Mrs. Ternan almost seems to have extra-sensory perception in running interference for her daughter’s reputation. Later, Dickens takes Nelly to the house that his friend Wilkie Collins (Tom Hollander) provides for his mistress, and Nelly emerges scandalized and furious at even the hint that she might partake of such a relationship. At this point, not even a kiss has passed between her and the middle-aged author.

The crux comes in a striking scene exactly halfway through the movie when Catherine Dickens makes a surprise visit to Nelly’s birthday party, bearing a piece of jewelry that Dickens’ had made for Nelly but that was delivered to her by mistake. By ordering his wife to take the gift to its proper recipient, Dickens is announcing his intentions to both women. Catherine, hurt but stoical, urges Nelly to understand that she will have to share Dickens with the public, and may never be sure which he loves best.

Though Dickens soon sends a letter to the Times in which he announces his separation from Catherine and defends the “spotless” honor of the unnamed young woman with whom he has been linked, there is, for reasons the movie doesn’t explain, no chance that he will divorce the one in order to marry the other. Thus does Nelly become that which she didn’t want to be: a famous man’s mistress. They decamp to France, where they have a son who dies in childbirth. On returning to England, they are caught in a horrific train wreck and Dickens emerges trying to make it seem that he was traveling alone.

The fascination of this story has much to do with the way it is told. In Fiennes’ handling, very little is stated in a straightforward or obvious way. It’s almost as if he took Abi Morgan’s screenplay (adapted from Claire Tomalin’s book) and stripped away its most utilitarian dialogue, leaving only hints and suggestions of emotions that then must be fleshed out by the actors. The method, whatever its source, makes for a narrative that’s constantly evocative, mysterious, almost impressionistic, and that involves the viewer in the pleasurably engrossing game of puzzling out the characters’ aim and motives, especially in the early parts of the story when the lovers’ attraction is conveyed through only the most subtle of looks and gestures.

The success of this gambit entails a range of fine performances, especially in the lead roles. Bewigged and whiskered, Fiennes creates an exuberant portrait of Dickens that encompasses his vanity and selfishness as well as his bounteousness and thirst for life. As Nelly, the luminous Jones conveys the young woman’s mix of awe, intoxication and anxiety as she is drawn inexorably into the orbit of a powerful older man. Among the terrific supporting cast, Scanlan deserves special commendation for her work in showing Catherine Dickens’ dignity and grace in heart-rending circumstances.

“The Invisible Woman” is one of those evanescent conjurings of a bygone time in which every part serves the whole. The most entrancing and persuasive evocation of Victorian England offered in any recent film, it reflects superb work on the parts of many contributors including cinematographer Rob Hardy, production designer Maria Djurkovic, costumer Michael O’Connor and editor Nicolas Gaster.