David Alvarado and Jason Sussberg’s documentary “The Immortalists” concerns the scientific effort to defeat the aging process, yet because it focuses so closely on the personalities of two scientists in particular, it is bound to be greeted differently by different viewers: those hoping for a cohesive, current overview of the campaign to extend human life (the subject of a recent cover story in The Atlantic) may be disappointed, while anyone looking for an entertaining double portrait of egghead eccentricity will find their interest fully rewarded.

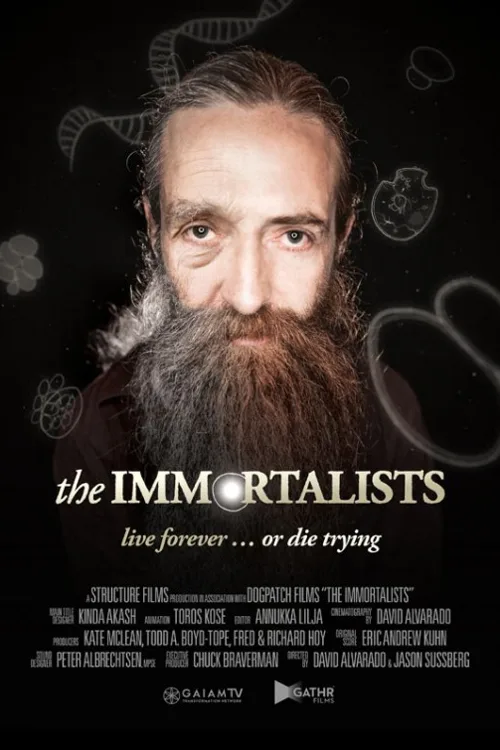

Those two main subjects are a well-matched pair. Aubrey de Grey, a hirsute, donnish Englishman, sports a luxuriant russet beard that makes him look like a refugee from the Pre-Raphaelites or a Russian monastery. Bill Andrews by contrast is quintessentially American in his salt-and-pepper ruggedness and unquenchable optimism. Both men are tall and fit with a buoyant athleticism that somehow seems tied to their quest of limitless life: When we first see de Grey, he’s poling a boat through the streams of Cambridge, where he lives; for his part, Andrews is an avid-unto-obsessive marathoner, running at least one hundred-mile race per month.

The film follows the men over several years, so we get to see how their work is reflected in their evolving lives. At first, they are on different continents and express contrasting ideas about their own motivations. De Grey says his research is purely for the benefit of humanity, although quick success would obviously help his mother–who says she’s 71 until he corrects her by saying that she’s in fact 81. Andrews, on other hand, admits that he’d like to win his battles in time to help to help his father, who’s 84 but still shares his son’s love of running.

The two scientists don’t cross paths till late in the narrative, when de Grey relocates to Silicon Valley, but the film makes clear from the first that they are very similar in bringing an almost religious fervor and conviction to their campaign to defeat aging. They both think it’s possible to extend human life indefinitely and they’re determined to make the necessary scientific advances themselves.

At the same time, their ideas about what the essential problems are and how to combat them are entirely at odds with each other. The film describes their different views in ways that the non-scientific-minded may or may not find comprehensible. The more general point, though, is that there’s no scientific consensus on these matters at present, so enterprising researchers like these two are operating as solo adventurers.

Fittingly, each has a complex romantic life to match his professional eccentricity. Andrews confesses that as a young man he broke off several engagements fearing that marriage would interfere with his work. Now in his 50s and never married, he’s engaged to Molly, a chipper blonde who shares his love of marathon running. After he completes a near-suicidal run in the Himalayas that nearly killed him two years earlier, they marry in a mountaintop Buddhist temple.

When we first see de Grey, he’s been married for many years to Adelaide, a Cambridge geneticist nearly two decades his senior. The two seem ideally matched both intellectually and romantically; the film even shows them sharing nude massages in a field. Yet when he decides to move to the U.S. and she’s professionally unable leave Cambridge, a rupture occurs. Later, she says that while she still loves him, she knows he has two younger girlfriends in California, where he muses that extending human life may make “polyamorous” relationships more necessary.

Such personal details account for much of the fascination of “The Immortalists.” Yet the film could use some more incisive examination of its subjects’ ideas. Most scientists working in their field simply foresee extending the human lifespan by a few or several years. De Grey and Andrews are outliers in asserting that there need be no limit to how long a person might live, given the discovery of ways to halt or reverse the aging mechanism.

But what would it mean for human society if people could live for a thousand years…or forever? De Grey and Andrews must have thought of such questions, and indeed must have been asked about them a thousand times. The film ultimately achieves a kind of poignancy in suggesting, after some of their intimates have died, that these men are valiantly fighting an enemy they can’t conquer. Yet its account of their quest would have been richer and more illuminating if it delved more into the social, ethical and philosophical ramifications of their work.

It is nonetheless a very well-mounted film, with outstanding contributions in Alvarado’s cinematography and Eric Andrew Kuhn’s subtly expressive score.